British jailers murdered American prisoners several months after the end of the War of 1812 in the last act of hostility between the U.K. and the United States.

-

October 2022

Volume67Issue5

Editor’s Note: Nicholas Guyatt is a historian, the author of six books, and a lecturer in modern history at the University of Cambridge. His most recent book is The Hated Cage: An American Tragedy in Britain’s Most Terrifying Prison, from which he adapted this essay.

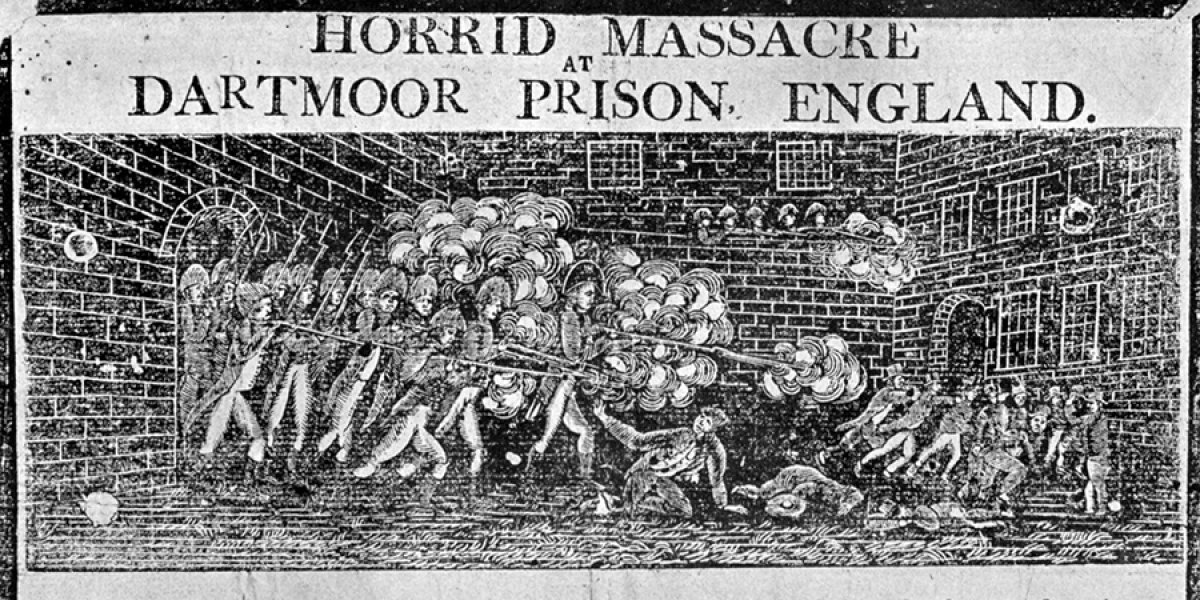

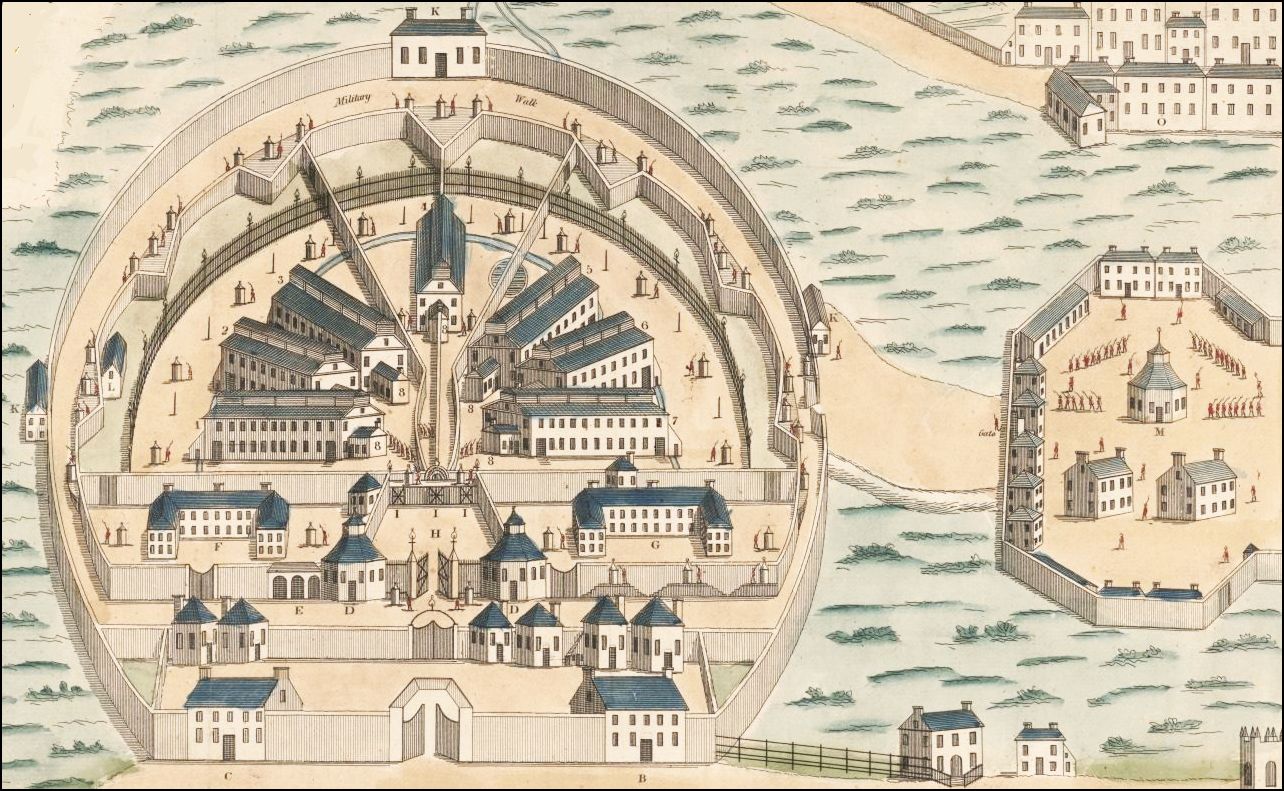

There were dead Americans in the yard. It was dark now and Frank Palmer didn’t know how many. Dartmoor prison, perched on high moorland in southwest England, was a place where even the British thought the weather was bad. The morning of April 6, 1815 had felt like the first day of spring, but the rare opportunity to spend time outdoors had only exposed the prisoners’ restiveness. The War of 1812 had been over for two months, and more than five thousand Americans were still locked within Dartmoor’s massive walls.

In the afternoon, hundreds of them had started an impromptu fight, throwing mud at each other and then at the British soldiers who were guarding them. The commotion made it easy to miss the smaller crowd of prisoners who were trying to punch a hole in the inner wall between the prison yard and the barracks building. Surely they didn’t think they could escape from Britain’s most fearsome prison? After the winter just gone, the guards believed the Americans capable of anything. When the “sport” in the yards led to the breaching of the prison’s inner wall, the situation deteriorated rapidly.

The shooting started after six in the evening. Palmer ran back to his prison block and cowered for an hour or more, listening helplessly to the screams. As British soldiers moved through the yard, prisoners fell in all directions. Crowds of Americans ran to the prison blocks and thrashed against the locked doors. The guards fired on them, too.

See also “The Paradox Of Dartmoor Prison”

by Reginald Horsman in the February 1975 issue

Frank’s estimation of “British humanity” had never been high. During the eighteen months he’d spent as a prisoner of war — in Bermuda, Canada, and now in Britain — he’d recorded terrible things in his diary. But nothing had prepared him for the guards firing into the prison blocks, through the doors and narrow windows, “killing and wounding without mercy” even those Americans who had tried to shelter from the trouble.

When the shooting stopped, the wounded were too afraid to emerge from the blocks and cross the yard to the prison hospital. Men lay bleeding and groaning all around Palmer's hammock until the prison’s governor, who was known as “the agent,” sent word that the injured should be brought out for treatment. The agent was a Royal Navy captain named Thomas Shortland who lived with his wife and children in a house at the front of the prison. When he had taken over at Dartmoor in December 1813, the Americans had viewed him as a good man. But survivors of the massacre were adamant: it was Shortland himself who had ordered the guards to fire, who had led the rampage through the yards, and who had “stamped on those who were already dead — or nearly.”

The Americans had lost their faith in Shortland’s decency during the bleak winter just past, and Palmer had little trouble believing the reports. By the light of a candle on the evening of April 6, he summarized the day’s horrors: “Is this not a sufficient proof of British barbarity?” he wrote in his journal. “The blood of the murdered will ever stimulate us to vengeance. WE CRY FOR VENGEANCE.”

Nathaniel Pierce, another prisoner who kept a diary of his time in Dartmoor, blamed the British turnkeys for locking the prison-block doors and denying inmates any respite from the slaughter. He accused Agent Shortland of sending “scouting parties” to kill prisoners who were hiding in the corners of the yard and of ordering the execution of one American who was carrying a wounded man on his shoulders. “It is an impossibility for me to describe the barbarity of this Captain Shortland,” Pierce wrote. The killings had been like “firing into a hencoop among a parcel of fowls.”

Americans knew all about British brutality; they had fought the Revolutionary War to escape it. But what Pierce saw that evening reminded him of one of the darkest days of America’s founding struggle.

“This is worse than the massacre at Boston in the year 70,” Pierce wrote. On March 5, 1770, a crowd of Americans protesting the British occupation of Boston had been fired upon by a line of Redcoats guarding the Custom House. Five Americans were killed; the grisly episode became a touchstone for the independence movement, from Massachusetts to Georgia.

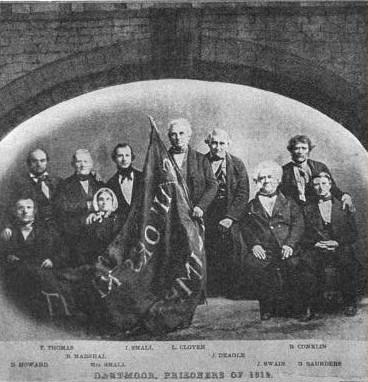

The Boston Massacre became a key part of America’s founding mythology. Nathaniel Pierce assumed that the Dartmoor Massacre would be no less enduring. Six Americans were already dead; another three would succumb to their injuries in the following days, and nearly three dozen had been gravely wounded. The terrible scene would be “long remembered by all true Americans,” Pierce wrote in his journal. Frank Palmer felt the same way. “Enough cannot be said on this subject,” he wrote. “Never (so help me God) will I make Peace with the English until I revenge the blood of my countrymen?”

When news of the killings reached the American papers later that spring, editors and publishers jockeyed to secure eyewitness testimony and to pour opprobrium on Britain. How could so many unarmed Americans have been killed in a British prison? What were they even doing there months after the War of 1812 had ended? As newspapers and congressional representatives pressured the administration of President James Madison, the survivors of the massacre awaited news of compensation — from the British or at least from their own government. Americans and Britons had been at odds with each other for more than half a century, since the successful conclusion of the Seven Years’ War in 1763 had prompted British politicians to demand more money from the American colonists to pay for the upkeep of the empire. The Dartmoor prisoners were only the latest American victims of “British Barbarity,” in Frank Palmer’s phrase, and they surely would not be the last.

Palmer was wrong about that. Although he and Nathaniel Pierce couldn’t possibly have known it, the nine men who lost their lives in the Dartmoor Massacre were the last Americans to be killed in wars between Britain and the United States. The half century of hostilities that had preceded the massacre gave way to more than two centuries of peace between the old enemies. As a consequence, Dartmoor — like the War of 1812 itself — was marooned by history.

The Boston Massacre retained its power in American memory because it explained why independence was necessary. The Dartmoor Massacre, on the other hand, became an awkward anachronism.

James Madison had no appetite for reopening the war in May 1815, when news of the killings at Dartmoor reached his desk. Instead, he and his diplomatic representatives carefully steered the controversy into a siding. The prisoners had learned at Dartmoor not to place much hope in their government, but they were amazed at how completely their cause would vanish from view.