With five major exploring expeditions west of the Mississippi, John C. Frémont redefined the country — with the help of his wife’s promotional skills.

-

Winter 2020

Volume64Issue1

Editor's Note: Steve Inskeep, the host of NPR's Morning Edition, has recently published Imperfect Union: How Jessie and John Frémont Mapped the West, Invented Celebrity, and Helped Cause the Civil War, from which this essay was adapted.

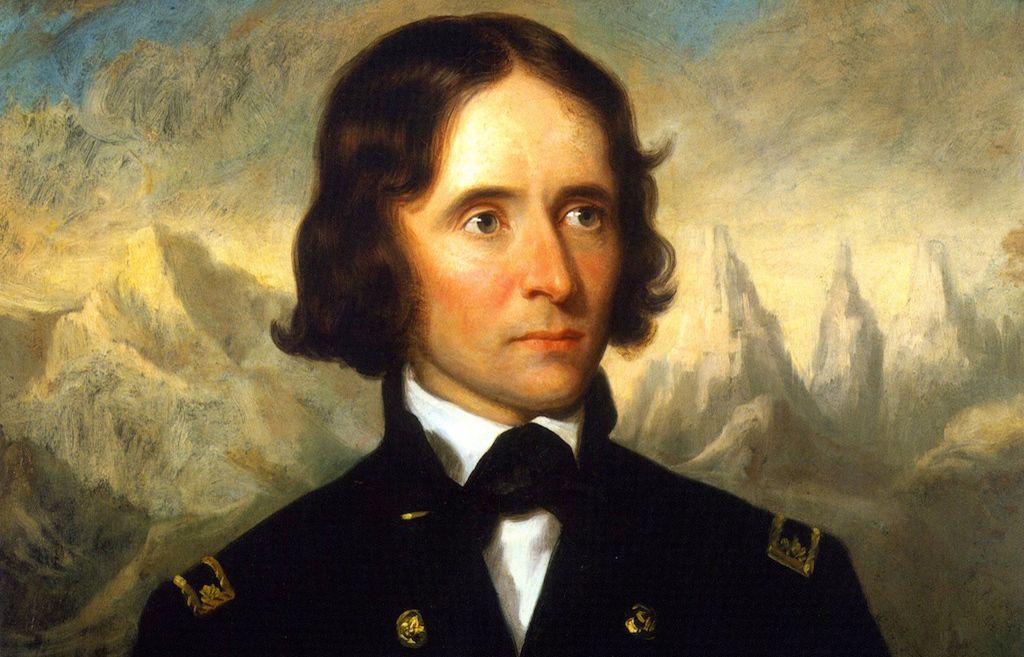

Of the many times John C. Frémont visited St. Louis, the most auspicious came in 1845. He was thirty-two years old U.S. Army captain with shoulder-length hair and a thoughtful expression. Arriving on a steamboat from the east on May 30, he disembarked at the crowded waterfront with two companions: Jacob Dodson, a son of free black house servants from Washington, D.C.; and William Chinook, an Indian from the faraway land called Oregon. It was fitting that Captain Frémont reached St. Louis with men from far to the west and east. His mission was to connect the Atlantic world to the Pacific, surmounting the natural barriers between.

Frémont served in an army unit called the Corps of Topographical Engineers, which had assigned him to draw maps of travel routes through the Louisiana Purchase. Twice in the preceding three years he had recruited small groups of skilled civilians to join him on expeditions that ranged across thousands of miles of prairies, mountains, and deserts. Each time their starting point was St. Louis, the commercial hub of Missouri, which was the westernmost of the United States. Now Frémont was about to command his third expedition, and his preparations in St. Louis should have been routine. He needed to hire men and buy supplies — camping equipment, rifles, food, brandy, and coffee. (The coffee was vital; he had run out once on the prairie, a painful mistake he would never repeat.)

But something happened as Captain Frémont made his customary rounds. His arrival was mentioned in a local newspaper, which created an unmanageable situation. James Theodore Talbot, a twenty-year-old aide who joined him in St. Louis, described Frémont’s problem in a letter to his mother.

“He was assailed by people anxious to accompany him” on his expedition, Talbot wrote. “Wherever he goes he gathers a little train.” The job seekers would not let him alone. Declining to stay with Talbot at the Planter’s House Hotel, where he might be spotted, the captain “hid himself in some French house down the City.” So many men asked for him at the hotel that a clerk vowed to put up a sign reading, “Captain Frémont Did Not Stay Here.”

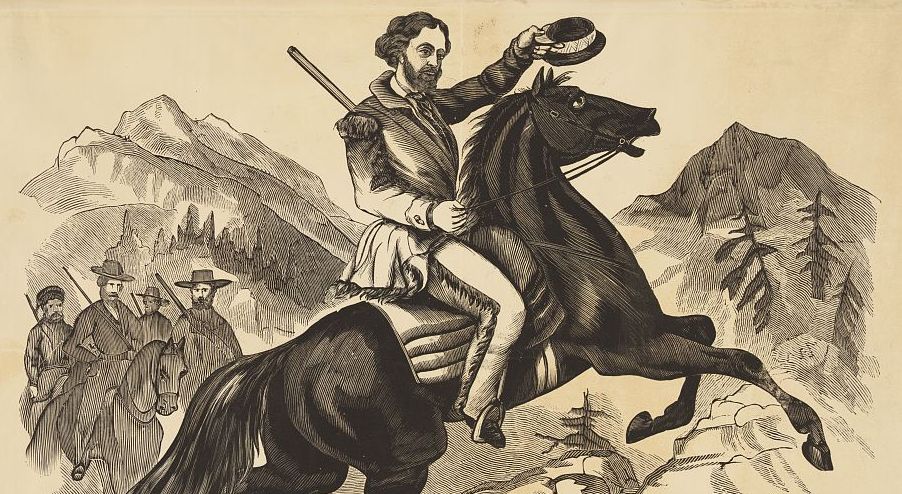

Frémont spread the word that he would meet potential recruits at a warehouse, where he might stand on a barrel packed with tobacco leaves to address them. But when he arrived before ten o’clock on the morning of June 2, he found an unruly mass. “You ought to have witnessed the scene,” Talbot wrote his mother. “Long before the appointed hour the house was filled, and Capt. Frémont found it necessary to adjourn to an open square. . . The whole street and the open space was crowded. We could easily trace the Captain’s motions by the denser nucleus which moved hither and thither. They broke the fences down and the Captain finally used a wagon as a rostrum, but it was impossible for him to make himself heard.”

Men were elbowing each other to reach him, wanting so badly to talk to him that they would not listen. Frémont, too polite and reserved to command the crowd, gave up and fled. But men found where he was staying and chased him even into his bedroom, forcing his free black servant, Jacob Dodson, to use all his “strength and vigilance” in a vain effort to keep them away. A St. Louis newspaper declared: “This is the strongest manifestation of the Oregon fever that we have yet witnessed.”

It was one episode in the life of John Charles Frémont, among the most famous men of his time. He had risen from obscurity just since 1842, when he commanded the first of his major expeditions. After traveling for months at a time on horseback and foot, often through deep snow, he went home to Washington, D.C., to write reports to the army about his adventures — and he told his stories so evocatively that his reports were excerpted in newspapers and published as popular books for the general public. His tumultuous arrival in St. Louis in 1845 marked a new phase in his work: the men he recruited that year deliberately rode outside the territory of the United States, crossing the mountains to reach the Pacific coast near San Francisco Bay.

There, his sixty armed men helped to trigger the United States’s conquest of the Mexican territory of California. This conquest was not even complete when the once-impoverished young officer began buying many square miles of California real estate, where he afterward struck it rich during the Gold Rush of 1849.

See also Frémont Steals California, by Sally Denton.

While it was natural that such a life would make him well known, Frémont’s fame grew to proportions that were not easily explained; other adventurous people of his era could hardly compare. Newspapers reported his every move. A contemporary journalist called him “the Columbus of our central wildernesses,” while a magazine in 1850 went further, listing Columbus, Washington, and Frémont as the world’s three most important historical figures since Jesus Christ. He was not even forty years old when Americans began naming mountains and towns after him. Europeans thronged to invest in his gold-mining projects, and followed each step of his adventures: 350,000 people attended a long-running stage show in London that featured paintings of his experiences. His fame made it possible for him to enter politics, lifting him to a seat in the Senate and propelling him in 1856 to become the first-ever presidential nominee of the newly established Republican Party.

What brought him such acclaim? Part was earned through genuine accomplishment. The conquest of California was one of the most consequential acts in the history of the United States. His reports pointed emigrants to Oregon, and helped inspire Mormons to settle near the Great Salt Lake. His maps were more reliable than earlier charts of the West because he insisted on mapping only landmarks he had seen himself. While others had previously walked the ground he traveled, his systematic observations showed how different parts of the landscape fit together. He collected so many specimens of previously unrecorded plants that botanists named many after him, and when he reached San Francisco Bay, he gave the harbor mouth its name: the Golden Gate.

His achievements were magnified by perfect timing: he explored the West just as the country was turning its eyes to it. The “Oregon fever” mentioned by the St. Louis newspaper in 1845 referred to excitement about settling the Pacific Northwest, which was matched by an interest in Mexico’s territory to the southwest. That same year the United States annexed the former Mexican territory of Texas; President James K. Polk took office after being elected on an expansionist platform; and a newspaperman, John L. O’Sullivan, wrote of “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.”

While O’Sullivan was not the first to talk of a transcontinental empire, his phrase “manifest destiny” entered the lexicon. It was debated in Congress and referenced in popular culture. The British performer George H. Hill, famed as “Yankee Hill” for the uncouth American he played in a stage show, worked the phrase into his popular stand-up routine in early 1846. He said he favored “a clean fight” for territory beyond the Rocky Mountains: “It is our ‘manifest destiny,’ and we cannot help it. Whoop, Whooray, whar’s the enemy?”

As Hill spoke, John C. Frémont was in California, about to begin the takeover — manifest destiny personified.

But the most important factor in Frémont’s fame may have been the person who made it possible for him to take full advantage of both his talent and the times: Jessie Benton Frémont, his wife. Born when women were allowed to make few choices for themselves, Jessie found a way to chart her own course. The daughter of Thomas Hart Benton, a senator who was deeply involved in the West, she provided her previously unknown husband with entree to the highest levels of the government and media.

It was no coincidence that his career began to soar a few months after they eloped, when he was twenty-eight and she was seventeen. “I thought as many others did,” said one of their critics, “that Jessie Benton Frémont was the better man of the two.” She helped to write his famous reports and some of his letters, serving as secretary, editor, writing partner, and occasional ghostwriter. She amplified his talent for self-promotion, working with news editors to publicize his journeys. She became his political adviser. She attracted talented young men to his circle, promoted friends, and lashed out at enemies. She carried on conversations with senators twice her age, offered her opinions to presidents even when they did not agree with her, and was gradually recognized as a political force in her own right.

Her timing was as perfect as her husband’s: she was pushing the boundaries of women’s assigned roles just as women were beginning to demand a larger place in national life. In the 1840s and ’50s, women were holding conventions to call for voting rights and also campaigning against slavery.

The Republican Party, founded to oppose the expansion of slavery, captured some of their energy — and when John was nominated for president, Jessie became part of the campaign in ways that no woman ever had. Her husband’s campaign literature featured songs of praise for Jessie; it nearly seemed like they were both running for president. Women attended campaign rallies even though they could not vote. Thousands of Republicans flocked to the Frémont house for a glimpse of John on the balcony, and then refused to leave until they saw Jessie too: “Madam Frémont!” they cried. “Jessie! Jessie! Give us Jessie!”

A newspaper said she could have been elected queen. Jessie Benton Frémont achieved a fame much like her husband’s, out of proportion to her accomplishments—unless we count her husband’s fame among those accomplishments. From their elopement in 1841 to their presidential campaign in 1856, the Frémonts pioneered a modern path to celebrity. Famous people in earlier times typically were revered because they held traditional positions of authority — kings, princes, clerics, generals, presidents. The cultural elites of Europe also celebrated writers and artists and people of interest.

But the Frémonts grew famous in a more democratic way. They worked through the expanding news media, which never before had reached so many readers or wielded so much influence. They spread their story to an increasingly literate public, and linked their names not to one, but to three great national movements — westward settlement, women’s rights, and opposition to slavery.

In attaching themselves to these movements, the Frémonts took part in events that redefined the country. The conquest of California did far more than simply extend the borders of the United States. It created conditions for the rise of a new, more global America. A nation that had been born on the Atlantic — a colonial extension of Europe, with an enslaved population from Africa — became a power in the Pacific with direct trade routes to Asia.

The story of John and Jesse’s union is many ways the story of the American union. They were early players in America’s constant struggles over equality, race, and identity. Their story is set in a time of open bigotry and state-sponsored racism: even outside the South, only five states permitted full voting rights for black men, and none allowed the vote to women. Yet it needs to be said that these were also years of American diversity.

America as we know it would never have come into being without the work of people who supposedly were not part of it. John, who seemed to define the new race of Americans, was the illegitimate son of a French immigrant. He would not have accomplished as much as he did without his partnership with a woman. When the Frémonts eloped, the only cleric who was willing to officiate was a Catholic priest. The volunteers for John’s perilous expeditions included men of numerous religions and backgrounds — a German immigrant mapmaker, French Catholic mountain men, free black men like Jacob Dodson, a Portuguese Jewish photographer, and Indians of several native nations. Numerous languages could be spoken around their campfires.

All of these people were creating the nation we have inherited, which is the legacy of all of them.