Although he was forced to resign as Nixon’s Vice President, Agnew’s “tough guy” persona set the precedent for subsequent anti-establishment figures including Donald Trump.

-

June 2020

Volume65Issue3

In the spring of 2016 the American Political Science Association polled forty scholars to name the worst vice president of the last century. Their consensus choice was an easy one: Spiro Agnew.

We disagree. Richard Nixon’s selection of Spiro Agnew to be his running mate in August 1968 proved to be one of the most underrated, consequential decisions in modern American politics, and it still reverberates a half century later. Although Agnew’s policy contributions during his five years in office were limited, he took on the important role of reshaping the trajectory of the Republican Party. His suburban, middle-class image, blended with his sharp-edged, anti-elite political style, launched his meteoric rise from an obscure county executive in a small border state to the man who was a heartbeat away from the presidency.

While there is no shortage of books about Richard Nixon, Bobby Kennedy, and the importance of the year 1968, scholarly work about Spiro Agnew is almost nonexistent. In our recent book, Republican Populist: Spiro Agnew and the Origins of Donald Trump’s America, we sought to give Agnew’s historical significance—for better or worse—its rightful place. We situate Agnew squarely, and prominently, in the lineage birthed by Barry Goldwater that is now ascendant in the GOP. It is a lineage that runs through Pat Buchanan’s presidential primary bids in 1992 and 1996, Sarah Palin’s brief star turn, the Tea Party, and most recently, Trumpism.

Since the 1960s the Republican Party has been based around a loose philosophy that has espoused support for smaller government, lower taxes, and a perceived toughness in foreign policy, particularly regarding the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The party found success at the national level in the past fifty years that had eluded it in the previous half century. And it has succeeded in achieving some of its primary policy purpose: the rollback of the New Deal/Great Society policy dominance that the Franklin Roosevelt/LBJ Democrats enjoyed from the 1930s through the 1960s.

Vice presidential scholars Christopher Devine and Kyle Kopko argue that the selection of the vice president often is justified on political, geographic, or policy grounds, but the electoral impact has been far from clear. The GOP establishment during these years nodded toward its populist wing by selective use of ticket balancing, best personified by vice presidential nominees like Bob Dole (1976), Dick Cheney (2000 and 2004), and Palin (2008). But in 2016 Trump was the firebrand at the top of the ticket. The more establishment figure (in this case Mike Pence) received the No. 2 spot to soothe the party’s old guard. In 1968 it was precisely this act of ticket balancing that helped launch Agnew’s career.

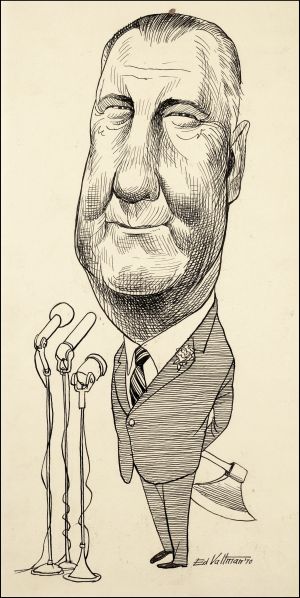

Agnew’s selection allowed Nixon to appear to be (at least in public) the establishment’s candidate. The Nixon tapes reveal that privately the president was always, in his own mind at least, on the outside of the establishment looking in. But with Agnew on the ticket, the Republicans embraced an anti-elitism that they had been wary of in past elections. With his classically good looks, slicked-back hair, and dark suits, Agnew talked sports with the passion of the average fan, which he was; he claimed to bear the attacks on him by the “elite” on behalf of his fellow frustrated middle-class citizens throughout the land; he loyally did his time supporting the president on the chicken-dinner circuit from Iowa to Idaho; and he played a key role in turning the white South toward the Republican Party.

It was Agnew who spoke most directly to the emerging Republican base because he was truly one of them, unlike President Trump’s blue-collar billionaire persona. Agnew’s core anti-elite message, while perhaps short on conservative ideology, was long on the politics of antiestablishment, white working- and middle-class resentment. It has since become an article of faith. Trump and Pence bottled the same magic in 2016, and it helped them capture the White House by turning Rust Belt swing states like Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin to the Republican column.

In 1968 and again in 1972 the Nixon-Agnew combination worked like a charm. While he was not an Ivy Leaguer, Nixon, having moved to Manhattan in 1963, was acceptable enough to the New England prep school wing of the Republican Party, which included legacies like the Bushes, the Lodges, and the Rockefellers. But Nixon could still connect with white, hardscrabble America in a way that spoke to his humble California upbringing. Agnew was something altogether different and new for the Republicans. Unlike the blue-blooded Henry Cabot Lodge, Nixon’s running mate in the 1960 presidential election, Agnew came straight out of Towson, Maryland. Time magazine dubbed him “Suburbman,” the type “whose life revolved around [his] four kids and [his] home, and who preferred family domestic life which, in years past, consisted largely of lawn sprinklers, pizza, ping pong in the basement rec room, Sunday afternoons watching the Baltimore Colts on color TV.”

Agnew’s lasting influence was his ability to mix politics and emotion; indeed, his scrappy temperament was arguably his most effective political weapon. Here he also shares the stage with Trump. While Nixon’s foreign and domestic policymaking legacy (obscured still by Watergate) included, among other achievements, the opening to China, the creation of significant environmental legislation, the signing of Title IX, and the negotiation of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, it was Agnew, by giving voice to those anxious white middle- and working-class voters, who played a primary role in forging a new Republican electoral majority. This same deal appears to be taking form in the first term of the Trump administration, where the policy details are being left to congressional Republicans while the president continues to cement an emotional bond with his voters, seemingly no matter what he does.

Just eight years removed from a seat on the Baltimore County zoning board and a single term as Baltimore County executive, Agnew had served fewer than two years as governor of Maryland when Nixon nominated him to be vice president in 1968. He was a national candidate with such a weak political resume that there is almost no historical parallel. That such a political novice could by 1969 become the third-most respected man in the country behind Richard Nixon and Billy Graham speaks volumes to the chord he quickly struck with the American people.

Agnew became a decorated World War II soldier, then moved on to law school, the suburbs, and to lawyering and eventually into politics. Nixon and his closest aides realized early on that Agnew was out of his league on policy matters and had very little idea of how to operate in the White House environment. In April 1969, just three months into the Nixon-Agnew team’s first term, H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, wrote in his diary: “VP called just before dinner and said he had to talk to Nixon. . . . Later [Nixon] called me into bedroom to report, furious, that all he wanted was some guy to be Director of the Space Council. May turn out to be straw that breaks the camel’s back. [Agnew] just has no sensitivity, or judgment about his relationship with Nixon. After movie we were walking home and Nixon called me back, again to ponder the Agnew problem.”

This book leaves the task of a full-on biography to others. Instead, we offer the following chapters as tight, selective snapshots from Agnew’s career framed within a larger political narrative. Together they reveal Agnew’s surprising ability to navigate the changing tides of post—World War II American politics. As his aide David Keene explained, “He was sort of a self-made guy who grew up on the block in Baltimore and went to night school, and people talked about how he’d studied his list of words in Reader’s Digest.” The future vice president’s father was a diner-owning Greek immigrant.

Agnew never made it into Nixon’s inner circle on foreign or domestic policy and later slammed his former boss for having “an inherent distrust of anyone who had an independent political identity.” Nixon’s staff thought even less of Agnew, but that would later play out in the vice president’s favor.

He was so far out of Nixon’s orbit that he had absolutely nothing to do with the Watergate scandal. Instead, he seemed destined to attend state funerals, take long goodwill trips abroad, and represent the White House on low-priority domestic issues. Nixon couldn’t stand Agnew personally, and he seriously contemplated replacing him in 1972 with Texas governor John Connolly, a conservative Democrat who would later become a Republican. He ultimately decided otherwise, conceding correctly that Agnew, in the meantime and much to everyone’s surprise, had become an icon to the GOP base.

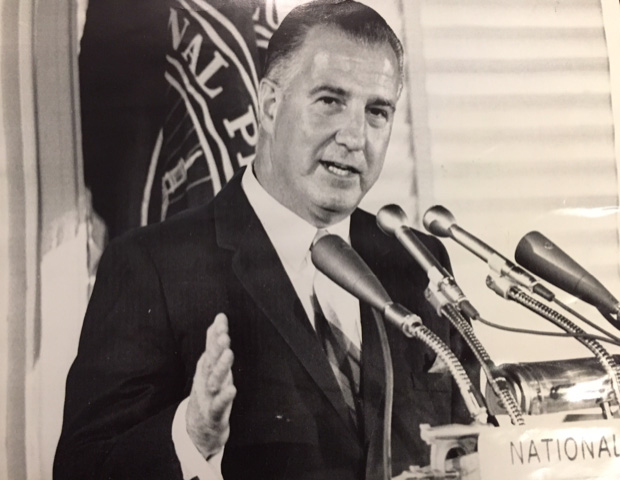

Instead of dwelling in vice presidential obscurity, Agnew in 1969 and 1970 turned himself into a valuable ambassador to the white South and the great silent majority. He was a leading fund-raiser at Lincoln Day dinners and the like, speaking to adoring crowds in places including Des Moines, Birmingham, and Boise. At these events he injected into the national dialogue the idea that the media was biased against conservatives. He attacked the Democratic Party for taking white southerners for granted, and he lashed out at the culture of permissiveness and the antiwar protests on college campuses. Agnew’s best-known speech on what he saw as the corrupting power of television network news identified a “small group of men, numbering perhaps no more than a dozen anchormen, commentators, and executive producers, [who] settle upon the 20 minutes or so of film and commentary that’s to reach the public.”

The 1969 speech became an instant classic, and while it is now a shibboleth of the Republican Party, it was originally met with hue and cry from the very media “elite” Agnew attacked — proving his point to his followers. But it also built a foundation, just as Pat Buchanan prophesized in 1970, for conservatives to “give consideration to ways and means if necessary to acquire either a government or other network through which we can tell our story,” thus connecting Agnew’s take on the media to the creation of Fox News and the alt-right.

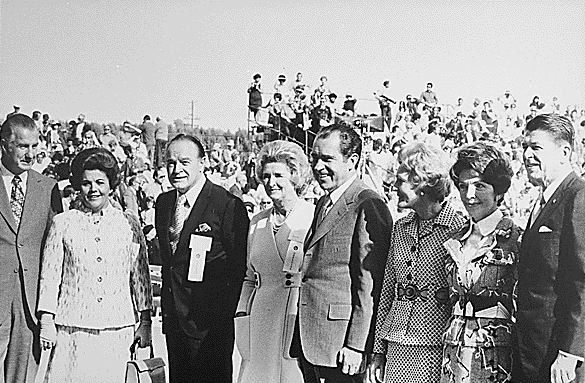

His attacks on the media catapulted Agnew to a new level of national political prominence. Forgotten now is that he was legitimately being touted, along with Ronald Reagan and Nelson Rockefeller, as an early leader for the 1976 Republican presidential nomination. But with George Wallace ready to make another run in 1972, it remained critically important for Nixon’s reelection that the emerging southern leadership of the Republican Party, including politicians like South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond, was behind the national ticket. Thurmond was on record as saying, “South Carolina will favor Spiro Agnew for president in 1976.” And it helped that Senator Barry Goldwater, the 1964 GOP nominee and spiritual godfather of the emerging conservative movement, also supported retaining the sitting vice president, pointedly arguing, “Agnew’s popularity equals that of the President.”

Of course, there would be no “Spiro of ‘76,” as the early bumper stickers proclaimed. The presidential talk was aborted by Agnew’s resignation in October 1973 and his replacement by Gerald Ford. As legendary Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee noted, “It is a measure of the darkness of the Watergate cloud that in only a few days, Agnew was history. The country welcomed the new Vice President, and returned to their seats to await the start of the final act.” Watergate consumed all the political oxygen in the aftermath of Agnew’s departure. Nixon resigned just ten months later.

The sordid details of Agnew’s sudden resignation — he was charged with tax evasion in October 1973 — explain part of his quick fade into history and his lack of historical recognition. While there is some speculation as to why he capitulated to the prosecutors so suddenly, there is little ambiguity about Agnew’s guilt. Nixon’s solicitor general, Robert Bork, argued that Agnew “had to resign; otherwise, he was going to jail.”

While the vice president would later maintain that he was innocent of the allegations that compelled him to resign, his primary line of defense in private during the summer and fall of 1973 was that everyone else in Maryland took kickbacks, too. Agnew accepted what amounted to bribes for construction contracts that started while he was in Towson and continued in Annapolis when he was governor later and during his time as vice president. As Richard Cohen, who covered the investigation for the Washington Post, later said, “This was a thoroughly corrupt man. He shook down everybody. . . . He was shameless.”

After pleading nolo contendere for failing to declare the bribes as income, Agnew disappeared suddenly from the political scene. He lived out an odd couple of decades, playing golf in Palm Springs with his pal Frank Sinatra and authoring a steamy spy novel that he tried to turn into a movie, as well as a memoir that focused on his version of the events that led to his resignation. His attempts to find work as a disbarred lawyer-turned-lobbyist for Middle Eastern princes and other international strongmen were embarrassing.

Public appearances were rare. There was, as he wrote later, a “more subtle punishment” inflicted upon him: “I cannot walk through a hotel lobby or down a street and simply be one of the crowd. Although I have none of the benefits of public life — no pension, no former statesman status, no diplomatic passport to ease my comings and goings in my international business affairs — I have retained a major impediment of public life. I have no privacy because I am recognized all over the world. When people stop and stare at you, you know some are thinking: “There goes Agnew, the guy who was kicked out of the vice-presidency.”

Even the U.S. Senate, where Agnew had presided from 1969 to 1973 as vice president, seemed to wish him away. The Senate withheld the traditional installation of his bust in its antechambers for more than two decades. When the statue was finally unveiled in 1995, the ceremony was pointedly not attended by either of Maryland’s U.S. senators. Agnew acknowledged mournfully, “I’m not blind or deaf to the fact that some people feel that this is a ceremony that should not take place.” He died a year later near his beach home in Ocean City, Maryland.

The vice president’s swift departure from the national spotlight, his sad plea bargain deal (which came on the heels of a public vow to fight until the bitter end), and his lack of any lasting policy legacy certainly are contributing reasons for his ghosting from American political history. The same handful of Agnew anecdotes and conversations are recycled in most biographies of Nixon. Agnew is occasionally worth a mention for pundits wishing to illustrate the perils of choosing an unknown running mate with little national experience. We believe, however, that the current narrative is incomplete.

Looking back now, we can see that Agnew’s nomination and ascendance as a national political figure helped fuse a broad-based coalition that connected Wall Street with the growing suburban middle class and a disgruntled white working class. It helped create a bond of political and cultural convenience between conservative country clubbers, a growing religious movement, and “betrayed” white southerners looking for a new home after Lyndon Johnson’s decision to back civil rights in 1964. Agnew made the most of his time in office to blaze a political trail that his protege and speechwriter, Pat Buchanan, would reprise in his own presidential campaigns in 1992 and 1996. But many Republicans originally met Agnew’s selection as vice president with deep skepticism.

Indeed, Agnew was as surprised as anyone to be chosen. After being nominated by Nixon at the Republican National Convention in Miami in August 1968, he told reporters that the selection had come “like a bolt out of the blue.” He also knew that “the name Spiro Agnew is not a household name. I certainly hope it will become one within the next couple of months.”

In his acceptance speech he stated outright, “I stand here with a deep sense of the improbability of this moment.” Many mainstream Republicans agreed. Michigan governor George Romney got 186 delegates (14 percent of the total) from the floor during the nomination process despite Nixon’s endorsement. Maryland congressman Rogers Morton, who knew Agnew well and would later be appointed chair of the Republican National Committee, privately told Nixon that while Agnew was potentially a very good candidate, he had a tendency to be “lazy.”

But as Richard Scammon and Ben Wattenberg pointed out in their 1970 examination of the Nixon coalition, The Real Majority, “Strom Thurmond may have liked John Tower on the ticket. Nelson Rockefeller might have liked Mark Hatfield on the ticket—but Thurmond couldn’t go home with Hatfield and Rockefeller couldn’t go home with Tower. Everyone could go home with Agnew—maybe grumpily . . . but it was a livable arrangement.”

Almost immediately after his nomination, and again after the victorious election, Agnew began to blaze a rhetorical path on race, culture, and the frustrations of Middle America. It got him on the cover of LIFE magazine in 1970, arms folded and peering out under the headline “Stern Voice of the Silent Majority: Spiro Agnew Knows Best.” He insulted and talked tough. Speaking to the GOP faithful and the newly converted at overflow crowds throughout the South and rural America, he went after the apostates in his own party and his perceived enemies with a vengeance. Agnew spoke directly to “the great majority of the voters in America [in 1968 who] are un-young, un-poor, and un-black; they are middle-aged, middle-class, middle-minded.”

A half century later Donald Trump followed Agnew’s playbook, likely without knowing it, in order to consolidate political support and national media attention. Denigrate minorities? Take on the news media and the biases of academics and intellectuals? Knock “political correctness” and elites? Publicly admonish members of your own party? Trump and Agnew could answer affirmatively to all these questions, separated by nearly fifty years.By 1969 Agnew was calling the news media biased and criticizing intellectuals and war protesters as “an impudent corps of effete snobs.” He stood for law and order and against anyone who opposed the Vietnam War. During the 1970 midterm elections Nixon deployed him as an attack dog not only against Democrats but against liberal Republicans who dared to challenge his administration. Politically and strategically, Agnew discovered how to make himself essential both to Nixon and to the creation of the modern Republican Party.

Trump’s campaign made explicit use of the Nixon-era buzzwords “silent majority” and “law and order.” Trump routinely used Agnew-like attacks on the perceived bias of the liberal media. Both men excelled at the political counterpunch and tilted against sacred norms and traditions of American political life. They each employed a slash-and-burn campaign style, carried their lack of elected political experience around as badges of honor, and are (or will be) remembered as overwhelmingly prideful men who lacked the humility to admit their mistakes. Put the similarities together and it is hard to deny that Spiro Agnew was a harbinger of things to come in American politics.

Agnew and Trump come together perhaps most closely as cultural critics for the white working class. As champions of the white everyman against Democratic Party liberal elites — the professional classes, the media, the entertainment community, the intellectuals, and the bien-pensants of the coasts — Agnew and Trump were viewed as heroes not just for their own personas but for the enemies they made. As Trump pointed out during the primaries, his followers were so loyal, he “could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and [not] lose voters.” Similarly, Agnew received thousands of letters from supporters pledging their undying allegiance even after he resigned and pled nolo contendere to tax evasion.

Both Agnew and Trump made it possible for a working stiff or mid-level office worker to vote Republican, because they countered the charge that the GOP was the party of the rich by pointing out the snobbery and elitism of liberal Democrats and their politically correct supporters.

Like Agnew, Trump had been a registered Democrat before switching parties. He had also been critical of Ronald Reagan. But Trump’s entrance and elevation into Republican Party politics was colored by the politics of race, much like Agnew’s sudden rise to national attention after the riots in Baltimore following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. As early as 2011 Trump challenged the legitimacy of Barack Obama’s citizenship. And the centerpiece of his speech announcing his candidacy focused on building a wall and making broad-brush generalizations about Mexican immigrants in the United States.

Trump’s political use of racialized offensive language is well documented. His playbook mimics Agnew’s in style and substance. And he is speaking to a similar constituency; the one-third to 40 percent of American voters who are Trump supporters resemble Agnew’s old silent majority population. Trump’s speeches have been given almost exclusively in Agnew’s old political stomping grounds—far from the East and West Coasts.

Agnew and Trump’s relationship with the press and the intellectual elites is also a core part of their political identities. Trump’s all-out assault on the veracity of the news media is in many ways the apotheosis of Agnew’s assertions in 1969 about the power of network news to shape public opinion. Trump’s pronouncements, like Agnew’s, are peppered with the law and order tilt of ending “American carnage,” calling out the media as “the enemy of the people,” and branding those that don’t agree with his immigration policies as politically correct. Like Agnew, Trump plays up his unfamiliarity with the ways of Washington, D.C., and rallies those left behind by the postwar/post-recession boom that exacerbated the divide between rich and poor, black and white, and urban and rural America.

The Agnew and Trump messages were, and are, angrier, edgier, and more accusatory than the Eisenhower or the Bush Republicans were used to, but they resonated with white America because they reinforced a perception that the civil rights movement or the Black Lives Matter drive was too militant, that intellectuals were too liberal, and that the media was too self-righteous and opinionated. The modern Republican Party, which in 2016 attained a position of dominance not seen since before Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, owes Spiro Agnew a debt of gratitude. Whether this makes Agnew the worst vice president or not, it certainly makes him deeply and historically significant.

Like Joseph McCarthy, to whom he is often compared, Spiro Agnew was much less significant as a man than as a phenomenon. In the 2016 presidential election cycle, as pundits and pollsters predicted Hillary Clinton’s victory, many were tempted to say that demographic shifts, the gender gap, and a coalition of urban elites and minority voters portended long-term Democratic success. The results of the election proved otherwise. Donald Trump’s victory in the electoral college exposed the political math that a new Democratic “coalition of the ascendant” is not yet able to rebrand the GOP as the party of economic elites and “the 1 percent.”

Now more than ever, Spiro Agnew’s Republican Party governs America. The new political roads Americans will travel in the twenty-first century will be across terrain shaped at least in part by this most unlikely of forgotten politicians who had no comeback or second act. His unprepossessing life has produced an oddly enduring legacy.

Portions of this essay were adapted from the authors' recent book, Republican Populist: Spiro Agnew and the Origins of Donald Trump’s America.