Veeck changed baseball forever, integrating the American League in 1949 and creating a variety of stunts and promotions to bring more fans to the stadium.

-

Summer 2017

Volume62Issue1

Entering the friendly confines of Wrigley Field in Chicago, a first-time visitor cannot help but be struck by the panorama of ivy-covered brick outfield walls, the traditional manually operated scoreboard, and an overall scale and proportion that seems perfect for baseball.

This iconic configuration is the handiwork of the late baseball legend Bill Veeck Jr. His father had been president of the Cubs, and young Bill grew up working for the team during school vacations. When the senior Veeck died unexpectedly in 1933, Bill dropped out of college and was hired by Phillip Wrigley, who had taken over the club the year before.

Bill started as an office assistant but quickly took on more responsibility. His role became directed at putting fans in the seats and keeping them happy. During games he roamed the stadium, gathering suggestions. He could often be found sitting shirtless among the fans, with a cigarette in one hand and a beer in the other. He favored the bleachers, in part because of his belief that one’s knowledge of baseball is in inverse proportion to the price of one’s seat, but mainly because of his genuine affinity for the folks in the cheap seats.

Cubs management listened to him. They installed his redesigned bleachers, along with wider seats, more concession stands, and those brick walls, where they planted the ivy that has come to define the park. They built a scoreboard above the bleachers that employed a system of lights and flags to let people passing by on the elevated railroad know whether the Cubs won or lost.

Today, more than 75 years later, the scoreboard, the configuration of the bleachers, the inner dimensions of the park, and the ivy-covered walls are just as they were when Veeck finished his first big assignment as a baseball innovator. It was just the beginning. Bill Veeck spent the balance of his life challenging and bringing change to the business of baseball.

A larger than life figure, he was a chain-smoking, charismatic, photogenic redhead with a big open face. He had a deep, compelling voice that writer Dave Kindred said “came as a train in the night.” Veeck loved the game—both the one on the field and the hardball played outside the lines by baseball commissioners and his fellow owners. He baited and berated the men in power. They hated him in return, and at critical junctures tried to oust him from the game, but he kept coming back. He successfully pushed for many of the major changes that took place in the game in the last two-thirds of the 20th century. The designated hitter, interleague play, a system of playoffs, free agency, and expansion of the leagues were all things that Veeck advocated and worked to achieve.

His role as baseball’s greatest promoter began in 1941, when he left the Cubs and bought his first team, the bankrupt and mismanaged minor league Milwaukee Brewers. He soon turned the once hapless team into a success, not only on the field but also at the box office by including all sorts of fan-pleasing extras—boogie-woogie bands, pig races, tightrope walkers—and giving away memorable prizes, such as 100 silver dollars embedded in a gigantic block of ice. Once he put on a "swing shift" ball game at 8 a.m. for night workers in war factories and served the fans breakfast cereal himself, dressed in pajamas.

Scheduling a game at that hour did not sit well with the commissioner or other owners, but it contributed to his growing reputation as the man who was going to put a new face on baseball. The national media embraced him. Sports writers tripped over each other for profiles and interviews—for which he was a most willing subject.

In 1942, after his second season with the Brewers, Veeck came up with a bold plan to purchase the Philadelphia Phillies and have a full roster of African Americans from the Negro leagues, who were excluded from the Majors by an unwritten but rigidly enforced color bar. The deal fell through when National League owners made certain that another buyer would be found for the Phillies, but Veeck would become a prime mover in the integration of the game after World War II.

In 1943 at the age of 29 he enlisted in the Marine Corps and asked to be sent to a war zone. After basic training, he was shipped to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, but he still played a role with the team by using war correspondents to get his thoughts and ideas back to Milwaukee. The fact that Veeck was conducting baseball business from a war zone was newsworthy and didn’t hurt attendance. But it was in that war zone that he was seriously wounded. An antiaircraft gun he was firing recoiled, smashing his right leg, which became infected. He was shipped back to the United States for treatment. After spending 15 of the 21 months he was in uniform in hospitals, part of his leg was amputated. Never one to wallow in self-pity, he threw a party for himself and danced the night away on his new prosthetic limb. But the ordeal wasn’t over; he required a continuing series of surgeries and skin grafts.

Veeck handled the pain with a singular sense of humor. “Suffering is overrated. It doesn’t teach you anything,” was his mantra, and he turned his new limb into a sight gag. He would light a cigarette, pull up his pants leg, and use the ashtray he had carved into the wood. Decades later, when he took a bad fall at the Baltimore airport, somebody asked, “Can I call you a doctor?” “No,” he shot back, “it’s the wooden leg, get me a carpenter.” His children report that he kept various shades of brown paint on hand in summer so that the tan on his wooden leg could deepen as the season progressed.

Veeck returned to Milwaukee after the war but soon sold the team. In late 1946 he bought the Cleveland Indians with a group of partners that included comedian Bob Hope. Veeck’s formula for success remained simple: create a great team and pack the stadium with loyal, happy fans. He became the first owner to allow fans to buy tickets over the phone, the first to sell season-ticket plans, and the first to stage special appreciation nights for various groups. He worked hard to broaden the fan base to include more women and children. When he came into baseball, women and children were tolerated at the ballpark. Now he marketed the game to them. In Cleveland, just after the war, he gave away nylon stockings when they were in extremely short supply. He built professionally staffed nurseries to attract women with infants.

Whenever Veeck took over a team, one of his first acts was to rip out the existing ladies rooms and replace them with clean, carpeted oases with soft lighting. (He was so proud of a woman’s restroom he built in Chicago’s Comiskey Park that he staged a contest to name it. The winning entry: Hall of Femme). He staged Mother’s Day promotions with free orchids to any woman with a child. It wasn’t altruism; his efforts helped him break attendance records, often even when his teams were losing.

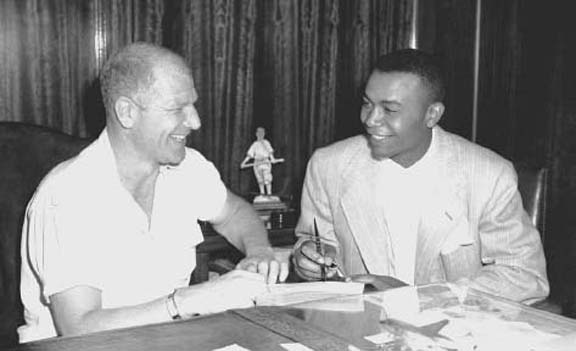

The highlight of Veeck’s baseball career came in 1948, when his Indians won both the American League pennant and the World Series championship. It was one of the most exciting—if not the most exciting—single season of the post-war Golden Age of the game. Veeck did it with an integrated team, on the field and off. He signed Larry Doby, the American League’s first black player, and hired the first black public relations officer, trainer, and scout. He signed the legendary black pitcher Satchel Paige, who helped win the Series—Cleveland’s last championship to this day. In 1949 Veeck brought 14 African Americans to Cleveland’s spring training. The passionate liberalism that he espoused and was never afraid to give voice to earned him the title “Abe Lincoln of Baseball” from The Sporting News.

Veeck’s next stop was St. Louis, where he bought the American League Browns, a terrible team—so bad that he said they were even “hard to look at.” The most common complaint was that the team lacked a leadoff batter who could get on base with any regularity. Veeck decided to stage a promotional stunt that would please the fans by giving the team a batter who would be sure to get on base—albeit just once. In deepest secrecy, Veeck signed a three-foot-nine-inch actor named Eddie Gaedel with a plan to send him to the plate to open the second game of a double-header against the Detroit Tigers.

At the appointed time, brandishing a toy bat, Gaedel stepped up to the plate and immediately crouched so low that his strike zone was only about 1½ inches high. Before the Tigers could protest, the Browns produced a bona fide contract, and the baffled umpire said, “Play ball.” Tiger pitcher Bob Cain, afraid of hitting the batter with a fast pitch and knowing there was no way to pitch to his strike zone, admitted defeat by giving Gaedel an intentional walk. Veeck had let a news photographer in on the plan, Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post Dispatch, who captured the whole event and brought it national attention. That day showed Veeck at his most flamboyant. Between the two games, Veeck had Gaedel emerge from a huge cake, which was then served to the crowd with free beer. The festivities also included the antics of Max Patkin, the reigning Clown Prince of baseball.

American League President Will Harridge, with the full support and collusion of the commissioner, voided Gaedel’s contract and banned “midget” players from the game. Veeck responded as only he could, by humorously demanding a ruling on whether New York Yankee shortstop Phil Rizzuto, at five foot six, was a short ballplayer or a tall midget. He then protested that six-foot-five Walt Dropo of the Boston Red Sox, who the Browns were playing next, was “too tall.”

The Gaedel stunt produced decades of notoriety. Veeck lived with the story for the rest of his life and embellished the tale with mock regrets. “Were it in my power to turn back the clock,” he declared 20 years after the fact, “I’d never send a midget to bat. No, I’d use nine of the little fellows, including the designated hitter.” Veeck quipped that his tombstone would read, “He sent a midget up to bat,” and then asked that the epitaph be cleaned up a bit to read more piously, “He helped the little man.”

Ironically, despite the negative reaction of baseball’s power brokers to the stunt, at a time when they feared losing their audience to the new medium of television, baseball was given a shot in the arm by this moment of frivolity. It got the country talking about the game.

Veeck held onto the Browns until 1953, when he sold the team to a coalition representing interests in Baltimore—and the Browns became the Orioles. He had tried to move the team himself, but the American League owners wanted him out of baseball. Veeck was pushing hard for reforms unpopular with many of his peers, such as shared television revenues, which he championed because he reasoned that it would allow for parity between the large- and small-market teams.

Veeck was an early advocate for expanding baseball to the West Coast, and within weeks of selling the Browns, he undertook a two-year study of westward migration for the National League. That effort paved the way for the Dodgers and Giants to move from Brooklyn and New York to their present locations in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Veeck’s next ownership was the Chicago White Sox in 1959—when the team won its first pennant in 40 years. He held the franchise until he was forced to sell it in 1961 due to ill health and what his doctors felt was a very short time to live. He moved his family to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where he not only survived but also wrote three books including Veeck: As In Wreck, which remains one of the most important baseball books ever written.

During this hiatus, motivated by a deep sense of fairness, he was the only owner to testify in support of outfielder Curt Flood during his landmark challenge to baseball’s reserve clause, which allowed a team to retain rights to players after their contracts expired. The successful challenge helped usher in free agency, breaking the owners’ stranglehold on the players. Veeck supported the players position even though he knew it would likely lead to the end of “mom and pop” owners like himself, who would be priced out of the game.

His final stint as an owner came in 1975, when he bought—for the second time—the nearly bankrupt, cellar-dwelling Chicago White Sox as they were about to leave the city. Within two seasons he rebuilt the team to a third-place finish in the American League West Division. And he continued to innovate. He installed the first exploding scoreboard in the Majors: When a White Sox batter hit a home run, fireworks, sound effects, and ten electric pinwheels all went off. He was the first owner to put players’ names on the backs of their uniforms; he introduced the singing of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” during the seventh-inning stretch, which became a national ritual; he began bringing relief pitchers in from the bullpen on golf-carts—one of the rare Veeckian touches that has faded away.

In 1980 he got out of baseball for the last time. Six years later, on January 2, 1986, he lost his long battle with cancer. His close friend and sometime business partner, the great slugger Hank Greenberg, told The New York Times: "Bill brought baseball into the 20th century. Before Bill, baseball was just win or lose. But he made it fun to be at the ballpark." In 1991 Veeck was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

His creativity and marketing genius were unlike anything in the history of sports. His financial innovations were initially deplored by other owners but were usually adopted by them eventually. For instance, he stunned the baseball world when he announced that he would depreciate players for tax purposes, thereby treating them like depleting oil wells. He saved his fellow owners, who were originally aghast at the idea, millions of dollars. Today Veeck is seen as a man decades ahead of his time. In 2004 Business Week picked him as one of the great business innovators of the previous 75 years.

At the heart of Veeck’s life story is the conflict between a stubborn, iconoclastic individual and an entrenched status quo. He once said: "The athlete who catches the imagination is the individualist, the free soul who challenges not only the opposition but the generally accepted rules of behavior. Essentially, he should be uncivilized. Untamed." He was talking about men like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, but of course he was also describing himself. Bill Veeck was a maverick, a visionary, and a showman extraordinaire.

Today—more than a quarter century after his death—America’s pastime will never be the same.

You can read more about Bill Veeck in the author's excellent book, Bill Veeck: Baseball's Greatest Maverick. (Bloomsbury, 2012)