Long before Roe vs. Wade, the practice of abortion led to fierce political conflict and public health problems in 1870s America.

-

Summer 2022

Volume67Issue3

Editor's Note: Kenneth D. Ackerman has written extensively on Gilded Age America, including his books Boss Tweed: The Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York and Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield.

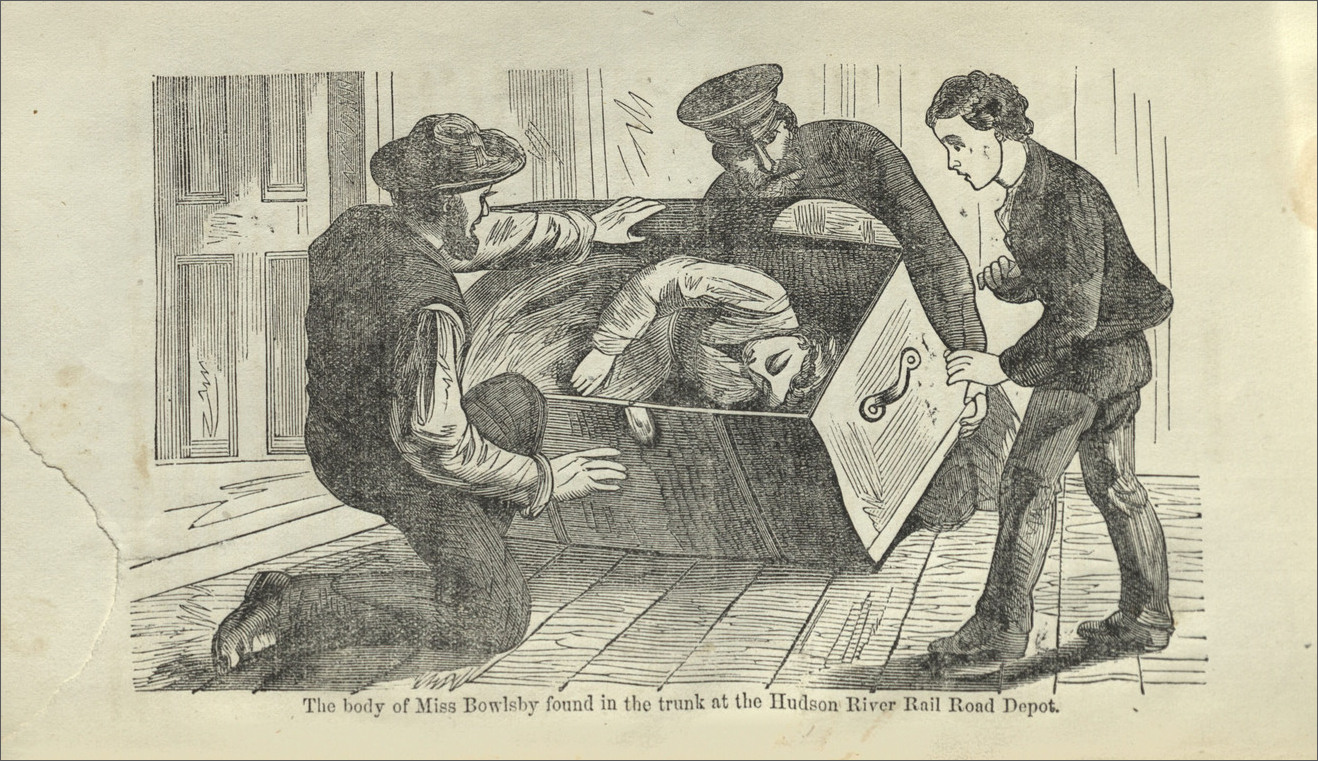

On August 26, 1871, workmen stacking a baggage trunk at New York City's Hudson River Railroad depot for shipment to Chicago accidentally dropped it on the floor. Noticing a terrible smell, they forced the trunk open. To their shock, they found the decomposing, naked body of a young woman. After days of painstaking detective work, police traced the trunk's movements to the home of a “doctor,” Jacob Rosenzweig on Second Avenue. The young woman, 20-year-old Alice Bowlsby, had died during an abortion procedure. The doctor had devised the baggage scheme to hide the evidence.

The Rosenzweig-Bowlsby affair dominated headlines in New York and across the country for two solid weeks, pushing even the breaking Boss Tweed scandal off the front pages. Newspapers detailed police efforts to identify the victim and track the killer. They called it "medical murder." Reporters descended on Alice Bowlsby's hometown of Paterson, New Jersey, where she had lived with her mother and two younger sisters, worked as a dressmaker, and impressed neighbors with her friendly, outgoing nature.

The reporters soon discovered that she had had a relationship with a 22-year-old man named Walter Conklin, also of Paterson and the son of a wealthy town alderman and rising officer at a local silk factory. Neighbors had seen Conklin and Alice Bowlsby keeping company; they reportedly had talked of marriage. Alice had even sown a white bridal gown that she kept in an attic. But Conklin, according to local gossip, had refused to marry her when she became pregnant, then brought her to New York to see Doctor Rosenzweig, the abortionist.

Hours after newspapers published the story, Conklin went to his father’s house, took a gun from a cabinet, and shot himself in the head. And though Rosenzweig swore his innocence, a jury convicted him of manslaughter by “medical malpractice” and sentenced him to seven years of hard labor at Sing Sing.

Abortion was as daunting a public issue in 1870s America as it is today. Passions ran high. But with a difference: Today, the procedure is relatively safe and, since the 1973 United States Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, it has operated in an established national legal framework. Before 1973, laws had varied widely state by state: thirty states had criminalized abortions across the board; sixteen made varying exceptions for rape, incest, or the health of the mother; and four allowed it more generally. A century earlier, in 1873, this landscape had differed even more dramatically.

On June 24, 2022, a sharply divided Supreme Court announced its decision—5 in favor, 4 opposed—to overturn Roe v. Wade, holding that no national right of abortion exists in the Constitution. The case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, involved a Mississippi statute that had outlawed abortion after the first 15 weeks of pregnancy. Chief Justice John Roberts voted to join the majority in affirming the Mississippi statute, while opposing the extra step of overturning Roe v. Wade.

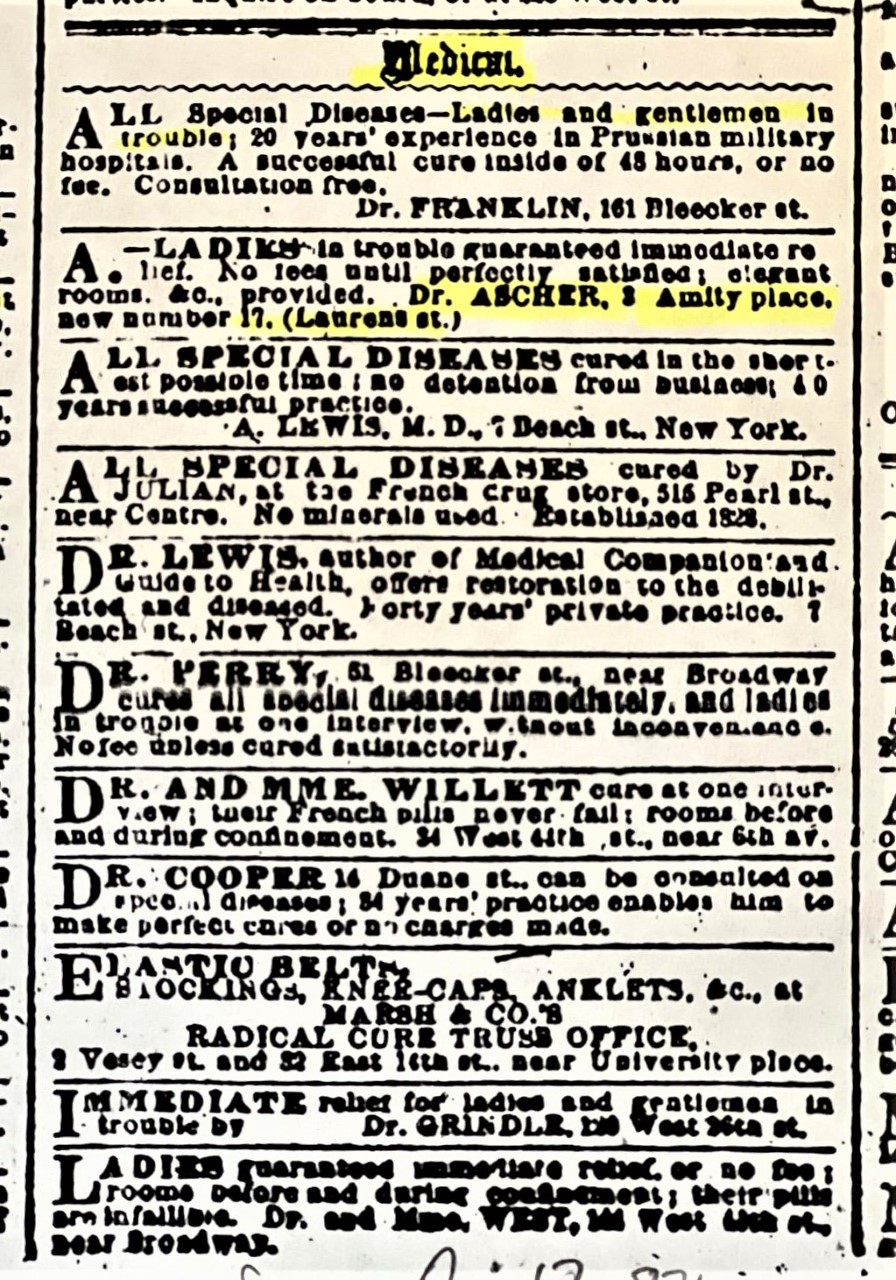

The history of what existed beforehand raises the obvious question: “what comes next?” The issue of abortion had reached crisis levels in New York in the 1870s. Victorian-era propriety aside, abortion was relatively common and tolerated in post-Civil War America, for wealthy and poor, married and unmarried women alike. At least a dozen abortion providers operated openly in New York. Many advertised in the newspapers. The same Doctor Rosenzweig convicted of killing Alice Bowlsby had run daily notices in both the New York Herald and Sun under an alias: "Ladies in trouble guaranteed immediate relief, sure and safe; no fees required until perfectly satisfied; elegant rooms and nursing provided. Dr. ACSHER, Amity-place &c."

Fees ran from $200 to $1,000 per procedure, which is about $5,000 to $30,000 in today’s money, far more than typical costs today for a first-trimester abortion, which range from about $350 to $950.

But, as the practice grew, abuses multiplied, especially involving the poor. Medical careny remained primitive and unregulated. State licensing of doctors in New York would not exist until the 1880s. Dozens of women died each year in clandestine operations, often at the hands of unscrupulous “irregulars” or "quacks" using crude procedures in unsanitary conditions. Stories spread of missing women being dragged lifeless from the Hudson River. When police decided to first place Alice Bowlsby’s body on an ice slab at Bellevue Hospital and publicly asked anyone in New York with a missing female friend or relative to try to identify her, hundreds came, lining up in the August heat for hours to examine her body.

For a young, unmarried woman like Alice Bowlsby, the restrictive society of the nineteenth century offered few options. Fear of scandal, rejection by one’s family, lack of social or financial support, and an attitude that squarely blamed the woman for what society considered a moral failure, all made the prospect of bringing an unwanted child into the world bleak. If the father denied responsibility, the mother and child faced poverty and scorn.

To end pregnancies, abortionists usually first tried drugs, home-made "feminine pills" often containing opium, mercury-based purgatives such as calomel and belladonna, and herbs such as ergot and tansy. These concoctions, based on traditional midwife remedies, were designed to induce convulsions and to shock the woman's system into spontaneous miscarriage. Often, they did nothing. At worst, they created addictions or caused internal bleeding, ruptures, or organ damage.

Surgery was a last resort. Anesthetics, ether, and chloroform, existed but remained expensive and rarely used. The process involved inserting often-unwashed metal instruments—probes, cervical dilators, forceps, and cutting tools—to pry, scrape, or cut away the fetus. Patients who survived shock, bleeding, and/or medical incompetence could die of gangrene. Modern standards of medical hygiene barely existed in 1871, even in the best hospitals. Abortion providers, working in small offices or apartments, often operated in blood- and pus-soaked aprons, spreading infection.

Abortion had been legal in most states until the 1850s. The traditional common law in America and England applied the “quickening” doctrine, the assumption that courts would not consider an unborn child alive until it showed some sign of movement, such as kicking the mother, usually three or four months into pregnancy. With "quickening" as a required element of proof and mothers generally immunized from prosecution, few cases were brought. More commonly, death in a botched operation would bring a homicide or medical malpractice charge against the “doctor.”

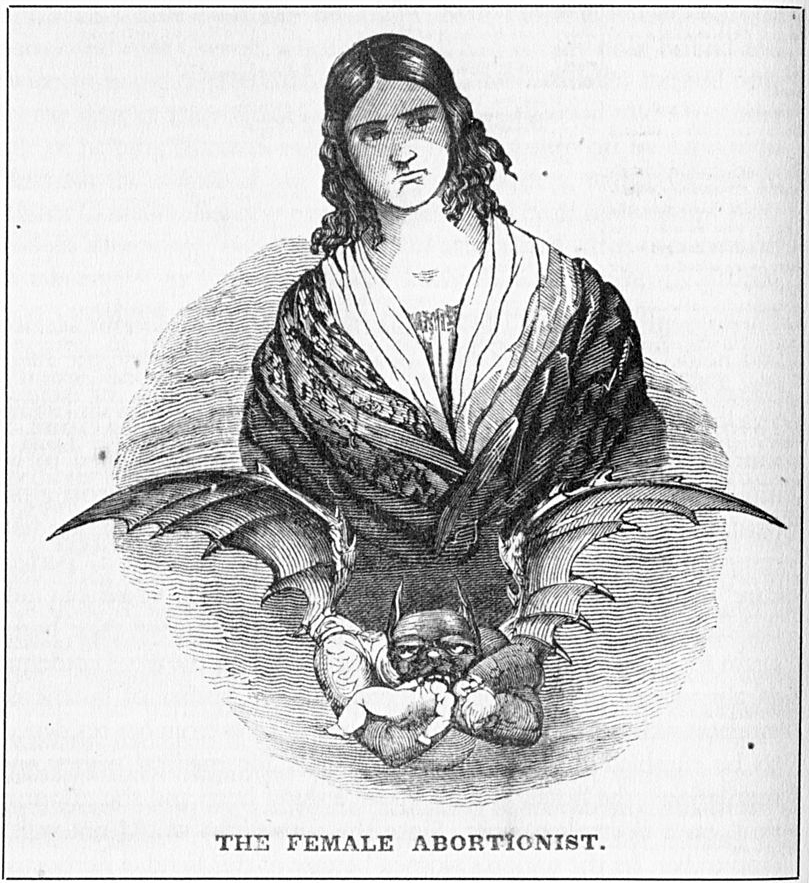

This began to change, though, around mid-century. Mainstream physicians, particularly members of the American Medical Association (AMA), which was formed in 1847, saw “irregular” abortionists and female midwives as competition and joined crusading journalists to expose them. These self-described reformers jumped on tragedies like the Rosenzweig-Bowlsby "Trunk Murder" to rouse public opinion. Earlier in 1871, the city had prosecuted a "Dr. Lookup" Evans, who was caught disposing of a dead patient. By then, New York State had repealed both the "quickening" doctrine and the mother's immunity.

The New York press fanned lynch-mob hysteria over the Rosenzweig-Bowlsby case with its graphic coverage. Within a year after Rosenzweig's 1871 conviction, state legislators amended the law to impose longer prison terms on abortionists and to ban the advertising or sale of abortion-inducing drugs or procedures. But the crackdown was just starting. Soon, another, bigger scandal would bring it to a head.

Enter Anthony Comstock and “Madame Killer”

Ann Lohman first opened her business in lower Manhattan as a “female physician” in 1838. She had no medical background. She was born in England, and her husband had died of typhoid shortly after their arrival in New York, leaving her to find work, first as a seamstress and midwife, before entering the abortion trade. Taking the name “Restell” to hide her identity, she advertised in newspapers and sold anti-pregnancy “French pills” and “celebrated powders for married ladies.” Business boomed. She soon opened shops in Boston and Philadelphia and hired salesmen to market her pills town-to-town.

Restell’s success made her a target. When a patient named Mary Ann Purdy died during an 1840 procedure, New York prosecuted Restell for homicide and a jury convicted her of misdemeanor abortion. Her lawyers appealed, claiming procedural errors in her trial, and the case was dropped. But in 1846, another customer, Mary Applegate, accused Restell of stealing the baby she’d midwifed and selling it for adoption. The next morning, a mob nearly burned Restell’s Greenwich Street house to the ground.

Because of these experiences, Restell was determined to build political protection for herself. She made payoffs to police and used as leverage the secrets she kept on the private lives of city leaders. Also, by the late 1850s, she had become very rich. After almost twenty years of catering to the secret “medical” needs of wealthy women in multiple cities, of selling her “French pills” and powders, and accepting occasional hush money from society figures trying to hide their personal scandals, her wealth literally rivaled that of Wall Street speculators and railroad barons.

In 1857, Restell discovered the Fifth Avenue lot where Saint Patrick’s Church planned to build an elaborate new cathedral and bid it out of sight. She built her own $150,000 mansion there and, from then on, performed her services in New York’s most fashionable district.

By the 1870s, Madame Restell was spending an estimated $60,000 each week advertising in city newspapers. When wealthy or well-placed women needed to “fix” an embarrassing “situation,” they turned to her. But her very fame made her, once again, a target.

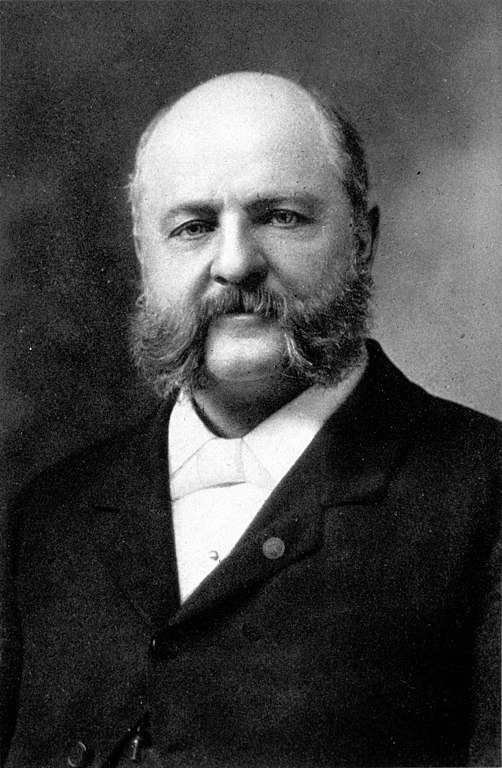

Anthony Comstock, a wide-whiskered 32-year-old Civil War veteran, had persuaded several wealthy New Yorkers in 1872 to finance a new Society for the Suppression of Vice. Comstock used this platform to launch a guerilla-style crusade against “obscene” literature, lottery operations, and abortionists. In 1873, Comstock traveled to Washington, D.C. and convinced the Congress to ban the sending through the mail of any writing or material found to be “obscene, lewd, lascivious,” “filthy,” or “indecent,” or any “article or thing” intended for birth control, abortion, or other “indecent or immoral use.” The Post Office appointed him Special Inspector to enforce the new Comstock Law.

Armed with this broad new power, Comstock began infiltrating pornography and gambling rings and arresting their operators. Three pornographers he targeted between 1873 and 1875 died violent deaths, two by suicide. Another, Charles Conroy, gouged Comstock’s face with a knife during an arrest. By mid-decade, Comstock had made himself a newspaper favorite, seizing thousands of books, pamphlets, and drawings that fit his definition of “obscene,” and portraying himself as a moral hero.

But critics complained that Comstock so far had only taken on small-scale criminals. So, to prove them wrong, he set his sights on Madame Killer herself, Ann Lohman “Restell.”

Using a fake name, Comstock began courting Restell in January 1878. He visited her Fifth Avenue home and asked for an appointment. Comstock told Restell he had a pregnant wife but not enough money to raise a child. Restell never suspected a trap. She sold him several of her special anti-pregnancy pills and told him what she’d charge for an abortion.

Armed with this evidence, Comstock returned to Restell’s home a few days later with two police detectives. They arrested her and seized a treasure-trove of banned goods: 10 dozen condoms, three syringes, 250 pamphlets, 500 “powers for preventing conception,” and about 100 boxes of abortion-inducing pills.

New York high society gasped. Who had more secrets about powerful, rich people like themselves than Madame Restell? Brought to trial, would she reveal the identities of her prominent customers to save her own neck?

For six weeks, the drama played out. Newspapers speculated over who had been seen most recently at Restell’s house, or whom she might blackmail to escape conviction. But times had changed. She hired a few top defense lawyers, but the publicity turned so hostile that no man in New York would sign her bail bond. She spent weeks in jail while raising the money for her release.

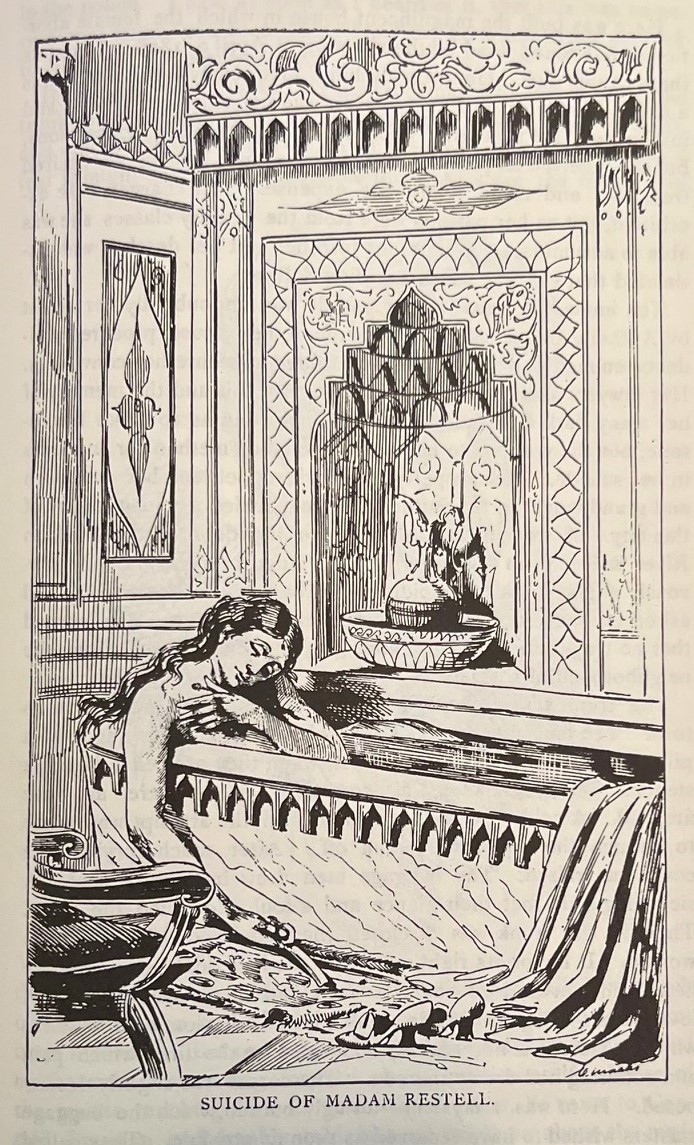

Beyond her show of bravado, stress had taken its toll on Madame Restell. Now 65 years old, Restell dreaded her upcoming court appearance; the prospect of being forced to reveal secrets, particularly the names of high-profile clients; and possibly wrecking the lives of dozens of women who’d trusted her discretion, let alone spending her old age behind bars. She privately fumed at how friends had abandoned her. In the pre-dawn hours of April 1, 1878, hours before the opening of her criminal trial, Restell made her choice. Rather than face public cross-examination, she decided to slit her throat with a carving knife in the bathtub of her Fifth Avenue mansion.

“A bloody ending to a bloody life,” Comstock crowed when word reached the courthouse. He would go on to lead a high-profile and controversial life. He’d live until 1915, establishing himself as a world-famous symbol of prudish intolerance, fighting liberals, free-lovers, artists, and feminists, the “Roundsman of the Lord,” as the popular writers Heywood Broun and Margaret Leech would dub him in their 1927 biography.

The Comstock-Restell drama forced New York’s leaders to face their own hypocrisies. Restell’s death ended this era of relative tolerance for abortion in America. State legislatures quickly stepped in to enact more severe restrictions, soon making abortion illegal to varying extents in every state.

After the 1870s, abortion deaths largely disappeared from front-page headlines, but not because such deaths ceased to occur. Attitudes ebbed and flowed, but, for the next ninety-five years, until the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, thousands of women would resort to illegal providers, and public talk of birth control would become taboo. By 1955, one widely-cited panel convened by Planned Parenthood estimated that between 200,000 and 1.2 million women were getting illegal abortions in America each year, the wide range reflecting the difficulty of tracking such illegal actions with any accuracy. Annual deaths were estimated in the thousands through the 1940s, though levels dropped sharply after that - into the hundreds - with the introduction of better antibiotics, the increasing availability of legal options, better hygiene, and other improvements in medical care.

After Roe v. Wade, abortions continued at about the same rate, peaking at about 1.4 million, as reported to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in 1990, and falling to about 630,000 in 2019. But, also according to CDC, abortion-related deaths have continued to plummet, averaging about 10 per year since 1973 and just two in 2018.

The changes in medical practice, law, and social-support systems surrounding abortion since the 1870s have been profound. But what hasn’t changed is how the issue continues to roil the country, touching the most intimate aspects of the lives of affected girls and women, and sparking passionate debate over profound issues of life and morality, culminating in the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturning Roe v. Wade. Doubtless, this case will not be the last.