Our classrooms are failing to pass down the essentials of what it means to be an American, a citizen of the United States.

-

Spring 2023

Volume68Issue2

Editor's Note: Richard Haass was a senior diplomat in the State Department and has been president of the Council on Foreign Relations since 2003. A frequent television commentator, Haass has written over a dozen books including the recently published The Bill Of Obligations: The Ten Habits Of Good Citizens, from which this essay was adapted.

No people should assume that their history, their heritage, is automatically handed down to the next generation. Collective identity, along with an appreciation and understanding of what lies behind it, is a matter of teaching, not biology.

This is true of particular groups of people, be they defined by religion or gender or race or geography or history. It is no less true of a people who constitute a nation — in this case, the American nation.

What worries me is that we are failing to fulfill the obligation to pass down the essentials of what it means to be an American and a citizen of the United States of America. Ironically, this does not apply to the newest citizens, immigrants. They often understand this country and its worth as much as or more than anyone. After all, they chose to come here. They studied to pass the exam required for citizenship. They often escaped a country where economic opportunities were limited, where they did not have the freedom to speak their minds or practice their religions. In many cases, they voted with their feet so they could vote.

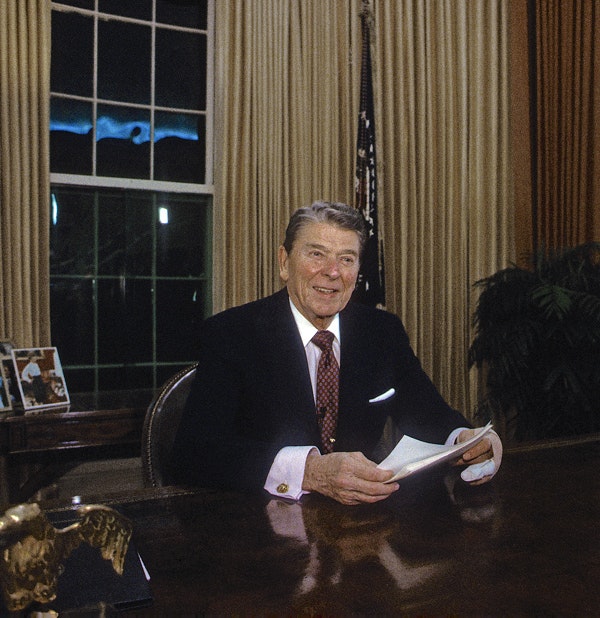

Instead, I am alluding to the many Americans who were born and grew up here but never received a proper understanding of their heritage, or forgot what they once knew. It is instructive that Ronald Reagan devoted the traditional warning found in many presidential farewell addresses to just this point. He began by noting his satisfaction with the “resurgence of national pride,” what he called the “new patriotism,” that occasioned his presidency, but then added this: “This national feeling is good, but it won’t count for much, and it won’t last unless it’s grounded in thoughtfulness and knowledge. An informed patriotism is what we want. And are we doing a good enough job teaching our children what America is and what she represents in the long history of the world?”

For Reagan, the answer to his question was an emphatic “No.” How did this come to be? Many schools do not take it upon themselves to teach about this country, possibly because some assume that the transmission of our past and its relevance to the present is automatic and already happening. Or they are not familiar with the central elements of the tradition. Or they do not value or agree with it. Or they have other priorities. Or they cannot agree among themselves as to what needs to be taught.

The United States is particularly vulnerable to this failure to educate its citizens about their heritage, as this is a country grounded not on a single religion or race or ethnicity (as are so many other countries) but on a set of ideas. These ideas are rooted in our history. Delineated in the Declaration of Independence, the new country made its case for breaking free from British rule as a means of creating a society in which all men are created equal, endowed with certain unalienable rights, including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. For its part, the government of the newly independent country would derive its mandate from the consent of the governed.

There are obviously major problems both with these words (the Declaration speaks of men, not people) and with the disconnect between the words and the American reality at the time — above all, slavery, limits on rights for women, the treatment of the Indigenous peoples who were living here when the colonists arrived, and subsequent discrimination against multiple waves of immigrants.

Nevertheless, the ideas represented a major step forward when they were articulated and they remain crucial today. The notion that a person’s fate is not determined by the circumstances of birth over which he or she had no control is radical, as is the idea that government derives its legitimacy from those it governs, not from a hereditary family or a self-appointed few.

In a more perfect world, a book such as mine would not be necessary because every American would get a grounding in the country’s political structures and traditions, along with what is owed to and expected of its citizens, in elementary school, in high school, and, if they go further, in college. These lessons would be reinforced by parents, family, and friends, along with community, religious, corporate, labor, and political leaders. Journalists would likewise play a constructive role.

Alas, that is not the world we live in. There is a good deal of talk about the budget deficit. It may be that our civics deficit is of even greater consequence.

Only eight states and the District of Columbia require a full year of high school civics education. One state (Hawai`i) requires a year and a half; thirty-one states half a year; and ten states little or none. And if you are somehow reassured at all by these numbers, don’t be, as the breadth and depth of what is taught is so uneven.

Things are little better at the next level. Less than a fifth of more than one thousand colleges and universities examined in one study require any civics education as a condition of graduation. The elite schools, including the Ivy League, are no better, and in fact tend to be worse, as many shy away from defining what it means to be educated.

Unlike high schools, the problem is not that courses are not offered, but, rather, that they are not required, and many students choose not to take what is available to them. Interestingly, the principal exception to this pattern is to be found in the service academies that educate future military leaders.

It should not surprise anyone that surveys suggest that many Americans know and understand little about their own political system. Many do not value it highly. One-third believe that violent action against the government is sometimes justified. These numbers suggest that the civics deficit will not turn into a balance, much less a surplus, if left to its own devices.

The question then is what to do about it. A basic idea is that no one should be able to graduate from a high school or college or university without a meaningful exposure to civics.

I write this in full knowledge that it is far easier to call for than to bring this about. At the high school level, there is the problem of limited time and resources and the requirement that other subjects be taught. It is essential to teach core intellectual skills—critical thinking, along with the ability to perform basic math and learning to read, as well as speak and write clearly—along with what are often described as non-cognitive skills such as punctuality, perseverance, discipline, and the ability to work with others. Other subjects, be they science, physical education, language, and music and art, for good reason have powerful advocates and constituencies. Less so with civics.

There is the additional problem that few teachers are sufficiently trained to teach civics well. And, on top of all this is the sheer scale and decentralization of American public schools: there are over thirteen thousand districts, 130,000 K-12 schools, three and a half million teachers, and tens of millions of students. Still, it is essential that public schools take on this task, as the one thing almost all Americans have to do is attend a school through the age of sixteen.

The problems at the country’s approximately four thousand two- and four-year colleges and universities (attended for at least some time by about 60 percent of high school graduates) are different, in that most colleges and universities enjoy great discretion as to what they offer to students on campus and what they require of students before they can leave campus with a diploma under their arm. There are a handful of institutions that have a core curriculum with a significant number of required courses, and a few at the opposite end of the spectrum that give students a free hand to determine what they study.

But the most common approach is to have distribution requirements and to allow the individual student to choose among dozens of courses to fulfill each of those broad requirements, in addition to what they need to do in their major area of study.

The problem is that most students get through their college years with no exposure to civics, as studying it is not essential to graduate and can be easily avoided by choosing other courses to fulfill the distribution requirements. The president of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore could hardly be clearer about the result: “Our curricula have abdicated responsibility for teaching the habits of democracy.”

Resistance comes from many directions. Professors tend to dislike teaching basic courses, preferring more specialized offerings reflecting their research. Students want to exert control over what they study; the priority for many, not surprisingly, is to take courses in those areas they see as practical and relevant in terms of their future career and compensation. There is also pressure on students to devote the bulk of their course work to their major area of concentration, something that leaves only a limited amount of time for other pursuits. Administrations and boards of trustees have failed to make the teaching of civics a priority, and they shy away from introducing core curricula, lest they scare off students who do not want to be meaningfully constrained.

This can and should be fixed by simply introducing a required civics course for all students in high schools and universities. Such a commitment and mandate are likely to come about only from external pressure: from state governments that oversee high school funding and requirements, from parents who pay for education, from school administrations who are unafraid to define what they judge to be an adequate education (and to differentiate themselves by doing so), even if it means that some students will not apply to those bodies that certify institutions of higher education.

I would like to think that requiring civics might actually become a selling point for those private and charter schools, along with the colleges and universities that do it. If some schools introduce the requirement and it flourishes, this could set in motion a truly healthy competition.

There is, though, what might be an even bigger problem: What to teach under the banner of civics? It is one thing to agree in principle that every student must study it and to make available the resources to teach it. But just what is “it”?

Recent disputes over how to teach matters relating to race, which at times have degenerated into violent confrontations, are an indication of how charged it can be to determine what children learn in schools. This is much more likely to be a problem in public high schools and publicly funded institutions of higher education, which suggests that experimentation might best begin in private and charter high schools and private colleges and universities, and gradually cross over into the public realm once they are shown to be desirable.

A solid civics education would provide the basics as to the structure of government (the three federal branches, and state and local government, along with their scale and cost), how it operates (or is meant to operate) within and between the branches, and those terms and ideas that are fundamental to understanding American democracy, including democracy itself - representative versus direct democracy, republics, checks and balances, federalism, political parties, impeachment, filibusters, gerrymandering, and so on. Both the rights and obligations of citizenship need to be highlighted.

Such a class should expose students to the basic texts of American democracy, including the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, pivotal Supreme Court decisions, major presidential speeches, and a handful of books that have stood the test of time. The curriculum should include the basics about American society and the American economy and how these facts have evolved over time. Teachers should emphasize the behaviors that democracy requires, i.e., the need for civility, the importance of compromise, the centrality of facts and where to find them.

Far more difficult is what to include in the way of history. There are any number of difficult questions: What events to include? What to emphasize? How to treat or cast certain historic phenomena or events? The “battle” between the 1619 and 1776 projects, two widely divergent narratives about the arc of American history, and, subsequently, over “critical race theory,” highlights just how controversial and divisive history can be because of how it frames the past.

My instinct here is to suggest that the major debates, events, and developments be studied, that any single framing be avoided, and where there is disagreement, that the various perspectives be presented. One possibility is for students to be assigned a range of readings and then asked to debate the competing interpretations of the past. The “Where to Go for More” section at the end of this book also includes a list of resources that can provide a foundation for such inquiry.

As a rule of thumb, the curriculum should not try to settle contentious matters of history or the present or advocate any particular policy, so much as present facts, describe significant events, and set forth what were and are the major debates over analysis and policy prescriptions. Simulations, in which students participate in a model Congress or policy-making activity, could prove particularly useful. One could similarly imagine a mock press conference or Supreme Court hearing, or structured debates of every sort. Simulations offer an opportunity not just to encourage students to learn more about issues and institutions, but also to put into practice democratic behaviors.

Over time, it would be ideal if something of a consensus emerged over what should be taught. Think about it: it seems borderline crazy that there would be competing approaches taught in different states or educational institutions if the goal is to build a common understanding of citizenship and the rights and obligations associated with it.

But this is where we are, and an attempt to install a single national curriculum for high schools and another for colleges would surely fail. It tells you something when a principal piece of legislation meant to address this problem, the Civics Secures Democracy Act of 2021, explicitly states, “Nothing in this Act shall be construed to authorize the Secretary of Education to prescribe a civics and history curriculum.”

But the time is right to have a debate over making civics required and to determine what might constitute a curriculum that would be both useful and broadly acceptable. It is difficult to imagine a more urgent and critical need if American democracy is to survive.