Often thought to have been a weak president, Carter was strong-willed in doing what he thought was right, regardless of expediency or the political fallout.

-

Spring 2023

Volume68Issue2

Editor’s Note: Kai Bird won a Pulitzer Prize for American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. He adapted the following essay from his most recent book, The Outlier:The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter.

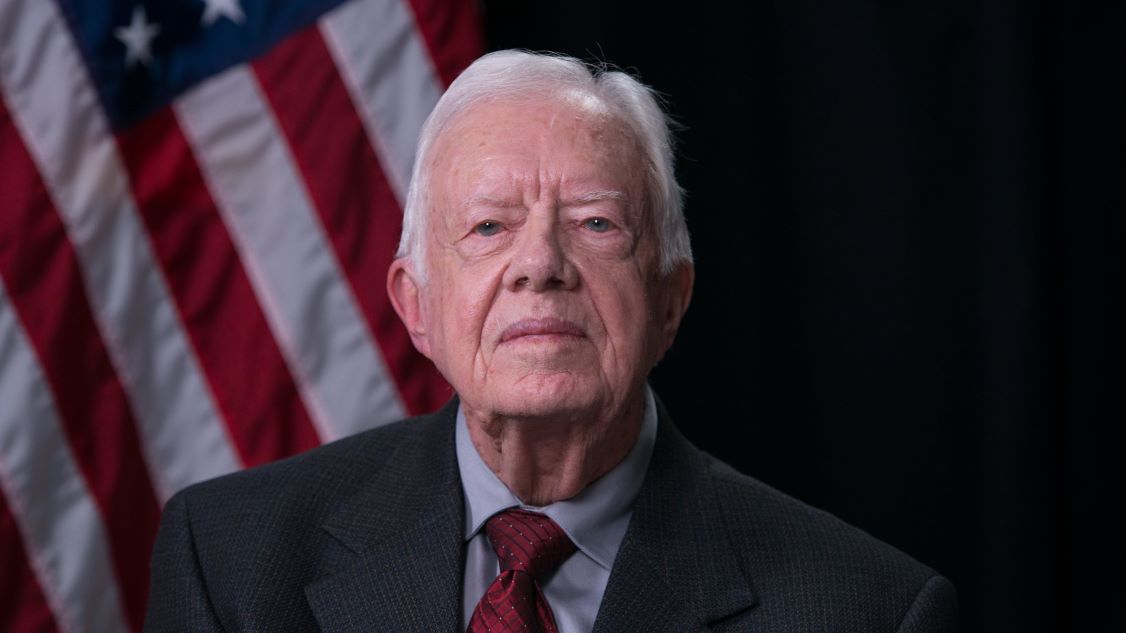

Jimmy Carter was perhaps our most enigmatic president. He is often celebrated for what he achieved in his four-decade-long post-presidency. Conservatives and liberals alike accord him the accolade of “the best ex-presi dent.” But most citizens and the punditocracy routinely label his a “failed” presidency, ostensibly because he failed to win reelection.

But in truth, Carter is sometimes perceived as a failure simply because he refused to make us feel good about the country. He insisted on telling us what was wrong and what it would take to make things better. And, for most Americans, it was easier to label the messenger a “failure” than to grapple with the hard problems. Ultimately, Carter was replaced by a sunny, more reassuring politician who promised that he would “make America great again.”

Conventional wisdom has not given high marks to Carter’s presidency. One historian described him as an “utter failure as a national leader.” Another labeled his a “mediocre presidency.” He was “long on good intentions,” complained this writer, “but short on know-how.” Gore Vidal called him “a decent man, if an inept politician.”

Carter is also perceived as having been a “weak” or hapless executive — the victim of runaway inflation, a militant ayatollah, and even a “killer rabbit.” Much of this is a simplistic caricature. No modem president worked harder at the job, and few achieved more than Carter in one term in office. Both his domestic legislative record and his radical foreign policy initiatives made his presidential term quite consequential. As a politician, most of the time, he was a non-politician, uninterested in the cajoling and dealmaking of Washington. This made him both an outsider and an outlier — “a person or thing situated away or detached from the main body or system.”

Far from being weak or indecisive, Carter repeatedly demonstrated his willingness to make tough decisions, despite the predictable political consequences. It may have been naiveté, but he invariably rebuffed his advisers when they cautioned him to do something because it was politically popular. They knew he was just as likely to do the opposite.

Indeed, Carter displayed an unbending backbone and moral certitude in dealing with such politically fraught issues as the Israel-Palestine conflict, the Panama Canal, nuclear weapons, the environment, and consumer protection. His greatest foreign policy triumph — the Camp David Accords, which led to a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt — never would have happened but for Carter’s vision.

Carter’s insistence on lecturing the Soviet apparatchiks about human rights may have contributed more to the disintegration of the Soviet system than did Ronald Reagan’s spending on Star Wars. He anticipated the end of the Cold War and proclaimed an end to our “inordinate fear of communism.” He asked us to think critically about the hubris of American exceptionalism. In the aftermath of defeat in Vietnam, he asked us to beware of foreign interventions. Carter refused to take us to war — even when the Iran hostage crisis posed an existential threat to his own reelection.

He was, as Garry Wills has argued, the “first American president to take seriously the entire post-colonial era that has remade the globe since World War II.” This was why he was willing to ram through the unpopular Panama Canal Treaty; he understood that America could not engage with this new post-colonial world without relinquishing its own colonial outpost in the Panama Canal Zone.

Against the advice of his inner circle, he hired Paul Volcker to strangle inflation, knowing full well that the Princeton-educated economist intended to make the economy scream as he faced reelection. Carter antagonized entrenched corporate interests by deregulating the airlines, the trucking industry, and railroads. Deregulation benefited millions of consumers — but it also tended to weaken labor unions, a core constituency of the Democratic Party. He forced through auto-safety and fuel-efficiency standards over the opposition of the Detroit auto companies. Seatbelts and airbags would become mandatory — and save thousands of lives each year. Environmentalists cheered when he placed millions of acres of Alaskan wilderness under federal protection — even as he accepted the fact that most Alaskans were outraged. For Carter, it was simply the right thing to do.

He stubbornly spent much of his political capital in his first term, acting as if he were a second-term president, which helps to explain the outcome of the 1980 election. His relentless pursuit of what he thought was a virtuous agenda made him plenty of political enemies. Southern conservatives turned on him for his determination to remake the judiciary, elevating more African Americans and women to the federal bench than all previous presidents combined.

Carter’s obvious compassion and affinity for the poor, disenfranchised Blacks of his south Georgia childhood made many white working-class citizens uneasy. If race is the third rail in American society, Carter never hesitated to touch it. He was a southern white man — but he was the first president to feel entirely comfortable worshipping and speaking in a Black church.

Core constituencies within the Democratic Party did not understand this southern man and distrusted his political pedigree. He presented himself not as a liberal per se, but just as a good-government progressive. He promised never to lie and campaigned in the wake of the Nixon-Ford era on the notion that the country needed a government as good as the American people. His message was integrity.

All of this sounded suspiciously naive. Many in the Washington pundit class ridiculed his soft Georgia twang and peanut- farmer persona. It was an unfortunate cultural disconnect — as if Carter had arrived from a foreign country. His religion was also seen by the establishment as a curiosity. He personally disapproved of abortion, but he always defended a woman’s right to choose and lobbied for passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. He criticized busing as a tool of integration, but ardently supported affirmative action. He was a southern Baptist who believed in the separation of church and state — and so, he refused to subsidize private Christian academies with all-white student bodies.

His social liberalism was tainted by a small-town fiscal provincialism, but Carter’s political sensibilities as a liberal on social issues were authentic. Historically, he was a product of the southern populist outlook that helped to build Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition. He was a southern liberal quietly but adamantly opposed to segregation, and, as governor of Georgia, he proclaimed an end to racial discrimination minutes after taking the oath of office.

During the 1976 campaign, the New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis found himself listening to Carter on the stump and concluded, “Jimmy Carter really does see himself fighting entrenched power, the status quo. He resents privilege, official arrogance, unfairness. He thinks of himself as one of the outsiders, those without power in society.” Lewis thought Carter was channeling an authentic “modern voice of that old American strain, populism.”

Carter presented himself as an outsider, running against Washington. In 1976, in the wake of the Watergate scandal that brought down Richard Nixon, this populist branding aided his rise to power. His timing was impeccable. At no other moment in American political history could such an improbable candidate have won the presidency. But governing was another matter. No one understood it at the time, but the mid-1970s marked a turning point in the country’s political economy.

The 1973 Middle East oil embargo led to surging energy costs and stimulated inflation. Simultaneously, global markets expanded dramatically, leading to the export of manufacturing jobs to the less-developed world. De-industrialization began to eliminate middle-class American jobs. In retrospect, it is clear that the liberalism of the New Deal era was under siege. The grand liberal coalition was falling apart—just as Carter was dealt the most difficult economic hand of any post-World War II president.

His response was complicated. He was for the poor and underprivileged. But his fiscal instincts were conservative. As a pragmatist and an engineer, he paid more attention to details and facts than to politics and ideology. He valued competency and expertise. He read all the papers and concluded — as did most economists — that the country faced a unique situation: a dismal combination of rising budget deficits, rising unemployment, and rising inflation.

As stagflation persisted, Carter insisted that the right response was to prioritize the fight against inflation by cutting the federal budget deficit. Inflation, he insisted, hurt the working classes more than the investor class. Following this logic, he was willing to sacrifice some social programs — but not the defense budget — in an effort to control what he thought were inflationary budget deficits. Naturally, this proved to be extremely unpopular with the liberal base of the Democratic Party — and, in retrospect, history suggests that the American economy could have sustained much larger deficits. Liberals complained that he could have spent more on social programs to stimulate job creation and less on a defense budget still premised on Cold War assumptions.

In any case, Carter was not adept at selling his fiscally conservative policies. He didn’t have the personality of a natural politician. He tended to think that he was the smartest fellow in the room. And he probably was. But he also had a stubborn streak and a surprising audacity. His self-confidence bordered on arrogance. As a southern Baptist, he was painfully self-aware that his pride was the deepest of sins. And so, he tried to compensate for his overweening intelligence by working hard to be humble and transparent. But inevitably, this cauldron of pride, self-confidence, and principled problem-solving came across as sanctimonious.

Republicans and Democrats alike were annoyed when he refused to barter with them. Liberal Democrats controlled both the House and the Senate and expected a conventionally liberal presidency — one who would endorse federal spending on a broad range of domestic programs, from pork-barrel water projects to national healthcare. But Carter looked at the budget numbers and determined that the country could no longer afford each and every liberal program. In his memorable but gloomy “malaise” speech, he lectured Americans that “too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption.” And when he said no to the liberals, he was accused of being a bland technocrat, self-righteous, and simply not a team player.

His arguments with the liberals in his own party came to a head over the fundamental issue of health care. By 1978, the idea that every American deserved national health insurance became a key issue within the Democratic Party. Senator Edward Kennedy championed this cause and used it to challenge Carter for the 1980 party nomination. Carter was as committed as Kennedy to the New Deal dream of bringing national health care to every American. But he looked at the numbers and made the political calculation that the liberal senator’s universal-health care bill didn’t have the votes. Neither did he think that Congress had the tax dollars to fund it without fueling inflation. Carter offered to crack the door open to universal health care with a bill to provide universal catastrophic care to every American. Kennedy, the labor unions, and the liberal wing of the Democratic Party rejected this compromise, and the senator from Camelot announced his run for the presidency.

Initially, Kennedy and his supporters were confident that they would prevail. But they had not reckoned with the unbridled self-confidence of the Georgia peanut farmer. Carter announced that he was going to “whip his ass.” And he did, ruthlessly doing what was politically necessary to turn back the challenge. Rolling Stone’s gonzo journalist, Hunter S. Thompson, once described Carter as one of the “meanest men” he had ever met. By this, Thompson meant that he saw in Carter a man marked by a certain righteous determination.

See also George Washington Carver and the Peanut by Barry Macintosh

Carter fended off the Kennedy challenge from his left — but he was not able to defeat the rising challenge from the right. The tragedy for this decent politician who believed in the power of government to help people was that he was eventually defeated by Ronald Reagan — who, upon taking the oath of office, proclaimed that “government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem.” The Carter White House years thus turned out to be a tipping point toward a profoundly conservative era. To Carter’s enduring regret, America became more partisan and more unequal. His presidency was all about personal character and decency. But, instead of becoming transformational, Jimmy Carter’s presidency marked a transition to decades of divisive politics.

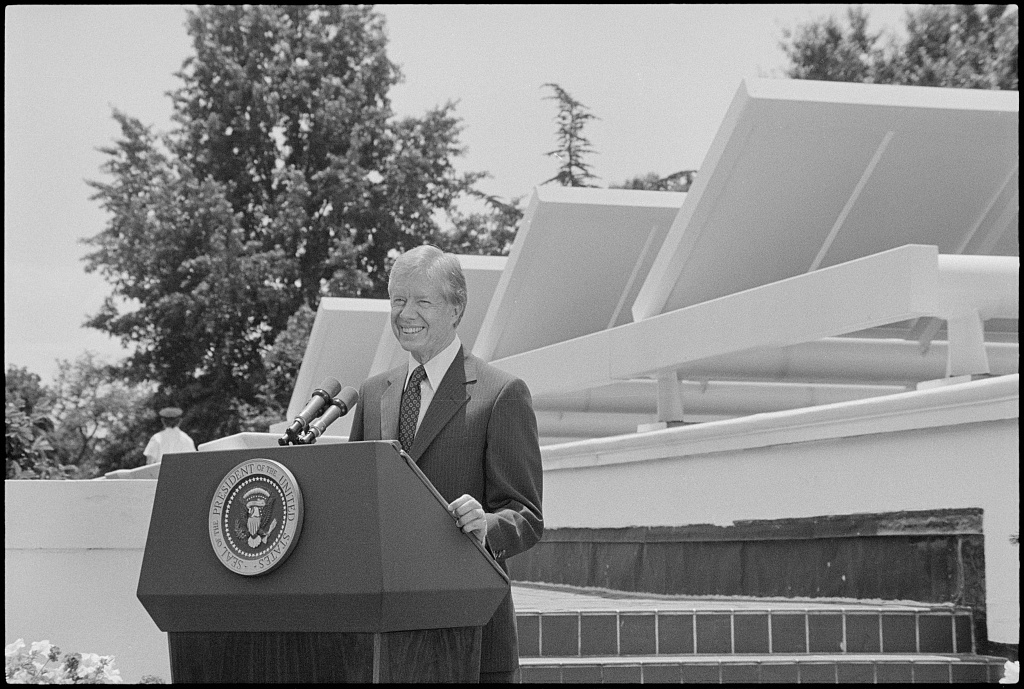

History will judge Carter as a president who was ahead of his time. In an age of limits, he asked us to conserve energy. He put solar panels on the roof of the White House before they were economical. He talked about climate change before it was ever fashionable. He was a “premature” environmentalist.

After the scandals of Watergate and Agnew, he scorned the trappings of an imperial presidency. Most Americans in the 1970s were not ready for this spartan vision of limits. Carter understood that the country had not recovered from the divisiveness of the Sixties. “These wounds are very deep,” he told us. “They have never been healed.”

Neither was the country ready for his message on the core issue of racism. As a white boy growing up in south Georgia, Jimmy Carter lived a childhood steeped in segregation and white supremacy. And yet his childhood playmates were mostly African Americans. His only neighbors were Black tenants. He experienced from the ground the great chasm between America’s beliefs about itself and the reality of inequality, poverty, and racism.

Carter was the rare southern white man who saw what African Americans saw — that America was not that “city on a hill.” He understood that the myths were myths and that America, both north and south, was in fact a country in need of serious healing. This was his strength as a politician and ultimately the source of his unpopularity in 1980. America was not ready for a politician who could engage in such truth-telling.

Indeed, as evidenced by the country’s reaction to the “malaise” speech given from the Camp David retreat, many Americans were perplexed and even unnerved to see a president willing to engage in such ruthless introspection and self-criticism. His efforts to persuade the country to confront its original sins were somehow both heroic and ill-fated.

“Our society is steadily growing more racially and economically polarized,” Carter wrote in 1996. “One reason is that many poor and minority Americans are convinced, with good reason, that the basic system of justice and law enforcement is not fair.” He said exactly the same thing in his famous “Law Day” speech in Georgia in 1974. Few listened.

Sadly, a far more divided America is today having to deal with many of the issues Carter grappled with forty years ago: environmental limits, national health care, the racial divide, income inequality, Middle East wars, and an excess of presidential powers. His was a decidedly unfinished presidency in practical terms, but also philosophically.

If Carter was ahead of his time, both his post-presidency and the story of his White House years now seem all too relevant.