In the blackest days of the Great Potato Famine in Ireland, Americans responded by organizing the first international humanitarian mission, sending food and provisions in the refitted warship USS Jamestown.

-

Winter 2020

Volume64Issue1

Editor’s Note: Stephen Puleo is the author of seven books of history including the bestseller Dark Tide, The Boston Italians, American Treasures, and The Caning. His most recent, Voyage of Mercy, from which this essay is adapted, tells the dramatic story of the American efforts to save the Irish people suffering from famine.

The destruction of the potato crop had occurred — or, rather, revealed itself — almost overnight. The Reverend Theobald Mathew, a priest based in Cork city, Ireland, was one of the first to observe and report on the disaster. In late July, he was traveling from Cork to Dublin and saw fields of potato plants blooming “in all the luxuriance of an abundant harvest;” a sight that heartened him after widespread potato crop failure a year earlier had resulted in severe food shortages, but not full-scale famine.

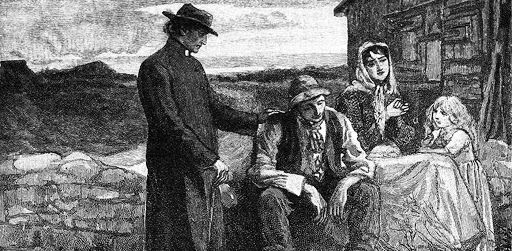

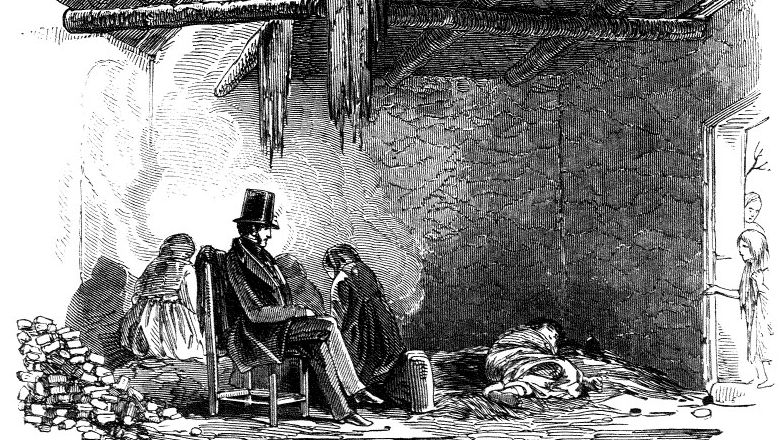

But six days later, August 3, 1846, during his return trip to Cork, Mathew’s spirit was shattered when he “beheld, with sorrow, one wide waste of putrefying vegetation.” The blight, caused by a fungus that thrived and multiplied in Ireland’s damp climate, had reproduced with lightning speed. In many places along the road, “the wretched people were seated on the fences of their decaying gardens, wringing their hands and wailing bitterly against the destruction that had left them foodless.”

Four days later Mathew expressed the worst in a letter to Charles Edward Trevelyan, assistant secretary to the Treasury in London: “I am grieved to be obliged to tell you that the distress is universal. Men, women, and children are gradually wasting away.”

Mathew, known best as Ireland’s “Temperance Priest;’ was a heroic and indomitable figure fighting — though mostly in vain — to save the lives of his starving countrymen. These imperiled citizens were not anonymous “famine victims,” but people he knew and loved — neighbors, parishioners, followers, friends. At this point, more than one-third of the entire Irish population depended exclusively on the potato for food and as a cash crop, but among poor tenant farmers, the proportion was even higher; a strong potato crop was their only hope for sustenance, for nourishment, for life itself.

Despite this backdrop of nearly unfathomable despair, the remarkable and unprecedented relief effort by the government and citizens of the United States to assist Ireland during the terrible famine year of 1847 is a story of hope, generosity, and soaring goodwill.

The mission undertaken by Captain Robert Bennet Forbes and the crew of the USS Jamestown to deliver tons of donated food to Ireland was the first step in a monumental effort that involved contributions from citizens of virtually every community in the United States and with the official imprimatur of the U.S. government.

Relief committees were established in key cities, and financial donations followed from Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Charleston; Baltimore’s relief committee noted that the bulk of the contributions were made by “many hard-working Irishmen, who earn their bread by the sweat of their brow.” New York quickly raised funds for Irish relief among both its Catholic and non-Catholic residents, with a promise for additional relief in succeeding weeks.

Smaller cities followed; relief committees were organized quickly in Albany, Chicago, Rochester, Richmond, Louisville, Providence, Natchez, Alexandria, and many others. Hamlets and small towns also took heed. The committee in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, raised money, and in Galena, Illinois, local women — who were praised as “Sisters of Charity “ in one newspaper — led the donation effort on behalf of Ireland. In Cooperstown, New York, author James Fenimore Cooper, a celebrity since his publication of The Last of the Mohicans in 1826, presided over a fundraising meeting, while students at Georgetown University organized a school-wide collection for famine relief.

But nowhere was the response as multipronged and vociferous as in Boston, whose reach included efforts across Massachusetts and New England. This was partly because the region’s already large Irish Catholic population increased its donations through parish fundraising efforts, encouraged by the sermons and pleadings of priests; partly because Massachusetts progressives felt that strong support for a humanitarian effort would serve as a salve for their anger about the Mexican War; and partly due to the guilt felt by Boston’s literati and intellectual core about the mistreatment of Irish immigrants who had already arrived in Boston.

In addition, that same group of educators, writers, religious leaders, and abolitionists prided itself on its support of progressive causes in general, including prison reform, mental health reform, and, of course, the growing anti-slavery movement. Writers in Boston, Concord, and across Massachusetts — Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville, John Greenleaf Whittier, Louisa May Alcott, and Emily Dickinson — all gave voice to Boston’s Irish relief efforts, as did abolitionists Charles Sumner, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and William Lloyd Garrison.

Ordinary Boston citizens also picked up the cry for residents of all backgrounds and faiths to come together to address a crisis unlike any they had seen. A letter to the Boston Post urged the writer’s fellow citizens to lay aside political differences and blame for the crisis, and to act upon the age-old biblical precept that “from those to whom much is given, much shall be required.”

It was unprecedented not only for the size and scope of American participation, but also because it was the first time the United States — or any nation, for that matter — extended its hand to a foreign country in such a broad and all-encompassing way for purely humanitarian reasons.

More than 5,000 ships would leave Ireland during the famine era carrying passengers fleeing utter destitution in their home country. The Jamestown was the first to travel in the opposite direction, laden with food and supplies for Ireland, and its celebrated mission provided the catalyst, the symbolic and physical impetus, that injected further momentum into the nationwide American famine-aid movement.

Prior to 1847, the bulk of interaction between nation-states consisted mainly of warfare and other hostilities, mixed with occasional trade; the entire concept of international charity existed neither in the moral consciousness nor as part of the political strategy of monarchs or elected leaders. If anything, such a gesture toward a foreign nation would likely have been viewed as a sign of weakness.

The Jamestown mission was, in modern parlance, the “tip of the spear,” the most visible and most celebrated component of America’s first full-blown charitable mission. The U.S. relief effort encompassed far more than the Jamestown, but it was the historic voyage of a retrofitted warship embarking on a mission of peace that most visibly symbolized the widespread willingness of the American people to offer up enormous stores of food and provisions to assist victims of the Irish famine.

For the first ten days of the voyage, however, Forbes and his officers worried that the Jamestown might not even reach Ireland. Snow, sleet, dense fog, ice, howling gales, and then “rainy dirty weather and variable winds” made navigation risky, especially with the ship’s inexperienced crew, and slowed the Jamestown’s progress early in the journey. The men struggled with new riggings stretched by constant dampness, and several of the sheets-the ropes attached to the lower corners of the sail-parted in the gale-force winds, keeping the crew busy night and day reattaching them.

The Jamestown’s large square sails were difficult to set amid drenching rain and unpredictable winter gales; unwilling to trust his green crew in the rough weather, Forbes often ordered the main sails reefed, a process of rolling a sail in on itself to reduce its area and stabilize the ship. Crashing waves, freezing temperatures, the spray of salty spume encasing ropes in a veneer of ice — all dangerous enough, Forbes knew, but even more so with a skittish crew.

Despite these adversities, exactly fifteen days and three hours after leaving Boston, the Jamestown came to anchor off the lighthouse in White Bay, in the outer part of Cork Harbor.

Like almost every captain, Forbes had relished the idea of piloting his vessel into Cork Harbor, the deepest and one of the largest in all of Europe — some said large enough to accommodate the entire British navy. From the Jamestown’s decks Forbes and his crew stood in awe at the scene before them.

Thousands of people lined the hillsides and the wharves. Men and children cheered wildly, women “waved their muslin;” and many people wept openly. An Irish band onshore played “Yankee Doodle;” while men in small boats waved their hats and shouted their greetings as the Jamestown passed.

The town of Cove and County Cork had expected the arrival of the Jamestown, but to actually see the big American sloop, the first foreign warship to enter a British harbor since the War of 1812, produced a mixed reaction of joy, gratitude, and disbelief

When news reached Cork city that the Jamestown had dropped anchor, bells rang out across the city to welcome the American vessel. Forbes and his crew were greeted by a jubilant reception committee “before the anchor had fairly bitten the soil.” Despite the deplorable condition of the country and its people, “the national heart yet can throb with gratitude for real kindness;” one journalist noted.

The voyage itself and the subsequent outpouring of charitable relief captured hearts and minds on both sides of the Atlantic, of wealthy and poor, of royalty and commoners, of poets and politicians. In addition, the events of 1847 have served as the blueprint and inspiration for hundreds of American charitable relief efforts since, philanthropic endeavors that have established the United States as the leader in international aid in total dollars and enabled it to assist millions of people around the world victimized by famine, war, and catastrophic natural disasters.

Today, of course, organizations from the Red Cross to Catholic Charities to the Salvation Army and hundreds of others participate with the United States government in providing food, medical aid, and supplies to disaster victims inside the United States and around the world.

Decades after the historic Jamestown mission, Robert Bennet Forbes wrote that the expedition “will be remembered in the history of philanthropy; and as the servant of generous people who gave their mite to the alleviation of the suffering poor of Ireland.”

From Voyage of Mercy by Stephen Puleo. Copyright © 2020 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.