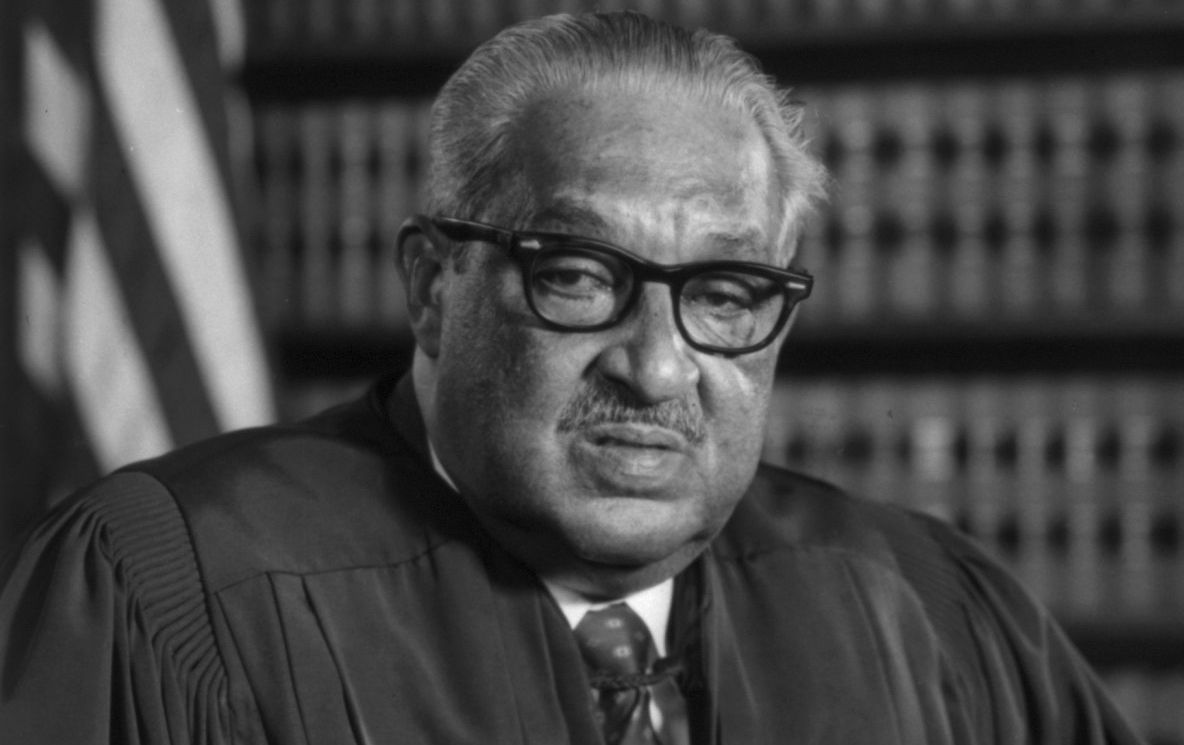

The architect of American race relations in the twentieth century, he ended legal segregation in the United States and became the first African-American on the Supreme Court.

-

Winter 2020

Volume64Issue1

Editor's Note: Juan Williams is a journalist and political analyst for Fox News and writes for The Washington Post, The New York Times, Atlantic Monthly, and other publications. He interviewed Justice Marshall extensively while he was still alive and published a biography, Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary, from which this was adapted.

Rumors flew that night. Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark had resigned a few hours earlier. By that Monday evening, Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall and his wife, Cissy, heard that the president was set to name Clark’s replacement on the Court the very next morning.

At the Marshalls’ small green townhouse on G Street in Southwest Washington, D.C., the phone was ringing. Friends, family, and even politicians were calling to see if Thurgood had heard anything about his chances for the job. But all the Marshalls could say was that they had heard rumors.

As Marshall dressed for Clark’s retirement party on that muggy Washington night of June 12, 1967, he looked at his reflection in the mirror. He replayed all the rumors he had heard about why the president was reluctant to appoint him to the high court. Thinking about it, Marshall got grumpy, then angry. His chance to be in the history books as the first black man on the Supreme Court was fading, and he felt abandoned. The word around the capital was that the nomination would be announced tomorrow. Marshall had heard nothing from the White House.

At the retirement party President Johnson was his usual dominating self, alternately bullying and ingratiating himself with both justices and the politicians in the crowd. When Marshall made his way through the faces surrounding Johnson, the president quickly greeted him with a wide smile. The two men loved to drink bourbon and tell stories full of lies. They were the same age and had strong feelings for each other. So it was no surprise when the president threw a long arm around Marshall and briefly pulled him aside. Johnson bluntly told him not to get his hopes up because he was not going to replace Justice Clark.

Marshall played it off with a laugh. Standing to his full height, he reminded Johnson that he didn’t need a job and there had never been any promise he would get to the high court. Behind his bluster, however, Marshall felt a fierce determination to argue with Johnson right there. It was Marshall’s style to apply pressure and fight. But this time he bit his tongue. It didn’t make sense to think he could bully Lyndon Johnson in the middle of a party and win. He drove home, cutting across the Mall, with the U.S. Capitol’s magnificent white dome glowing to one side and the towering Washington Monument on the other. The nation’s grand symbols made him feel small, an outsider. He had missed his chance.

The next morning, Tuesday, June 13, Marshall was in his office at the Justice Department on Pennsylvania Avenue when his secretary got a call from the attorney general Ramsey Clark, who was also the son of the retiring Justice Tom Clark. It was just before 10:00 A.M., and Clark told her he was coming down to see Marshall and to keep everyone else out.

When Clark got into Marshall’s office, he asked him what he was doing later that morning. Marshall replied that he was going to the White House to speak with a group of students. Clark told him to go over fifteen minutes early and stop in the Oval Office. Marshall pressed Clark to tell him what was going on. Clark said he didn’t know. But given the spate of rumors over the last twenty-four hours and the disaster at the party, Marshall figured this trip was for Johnson to stroke him and tell him why he didn’t get the job.

When he was finally called into the Oval Office at 11:05, Marshall saw Johnson, all by himself, bent over the news service ticker-tape machine. While Marshall waited for the president to turn around, he quickly glanced about the Oval Office. In the far corner was a bronze caricature of a frenetic President Johnson running while holding a phone in one hand. On the marble coffee table Marshall could see a bunch of index cards and papers, some of which had spilled onto the green rug under the president’s rocking chair.

Nervously, Marshall coughed to get the president’s attention. Johnson spun around, as though surprised, and said, “Oh, hi, Thurgood. Sit down, sit down.” Marshall moved toward the couch and sat next to Johnson’s rocking chair. Johnson made small talk with the fidgety Marshall until he abruptly turned to him and said, “You know something, Thurgood? ... I’m going to put you on the Supreme Court.”

Marshall was stunned. All he could say was “Oh, yipe!”

Hearings for most Supreme Court nominees began within a week of the nomination. Byron White, President Kennedy’s first candidate for the Court, had been nominated and confirmed within eight days. Abe Fortas, President Johnson’s first, had to wait only fourteen days. Thurgood Marshall was different. It would be seventy-eight days before his name would come up for a vote of confirmation in the Senate, where segregationists like Strom Thurmond, James Eastland, and John Stennis held power.

In the two and a half months between the nomination and the vote on Marshall, his record as a lawyer, his writings, his drinking, the women he slept with, and his family came under the intense scrutiny of FBI and Senate investigations. Sen. Robert Byrd, Democrat of West Virginia, wrote to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, asking if there was information about Marshall’s ties to Communists. Another senator focused on uncovering evidence that Marshall hated whites; other senators loaded up on detailed legal questions, hoping to reveal gaps in Marshall’s knowledge of the law that would disqualify him for the high court.

But the larger topics for Marshall’s opponents were still left unanswered: Who was this man? How did a black man so despised by millions of segregationists rise past Jim Crow political power to become a federal judge, the first black solicitor general, and finally to stand at the door of the highest station of American law, the Supreme Court?

Simply put, where did this Negro come from?

All his life Marshall had been an integrationist. If black people could mix freely with white people, study and work together, he believed, there would be no racial problems in America. He had pushed that theory in courtrooms throughout the nation. His lifework made him one of America’s leading radicals.

As a suit-and-tie lawyer, however, Thurgood Marshall was the unlikely leading actor in creating social change in the United States in the twentieth century. His great achievement was to expand rights for individual Americans. But he especially succeeded in creating new protections under law for America’s women, children, prisoners, homeless, minorities, and immigrants. Their greater claim to full citizenship in the Republic over the last century can be directly traced to Marshall.

Even the American press has Marshall to thank for an expansion of its liberties during the century. But for black Americans especially, Marshall stood as a colossus. He guided a formerly enslaved people along the road to equal rights.

Oddly, of the three leading black liberators of twentieth-century America — Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X — Marshall was the least well known. Dr. King gained fame as the inspiring advocate of nonviolence and mass protests. Malcolm X was the defiant black nationalist whose preachings about separatism and armed revolution were the other side of King’s appeals for racial peace. But the third man in this black triumvirate stood as the one with the biggest impact on American race relations.

It was Marshall who ended legal segregation in the United States. He won Supreme Court victories breaking the color line in housing, transportation, and voting, all of which overturned the “separate-but-equal” apartheid of American life in the first half of the century.

It was Marshall who won the most important legal case of the century, Brown v. Board of Education, ending the legal separation of black and white children in public schools. The success of the Brown case sparked the 1960s civil rights movement, led to the increased number of black high school and college graduates and the incredible rise of the black middle class in both numbers and political power in the second half of the century.

And it was Marshall, once he became the nation’s first African-American Supreme Court justice, who promoted affirmative action — preferences, set-asides, and other race-conscious policies — as the remedy for the damage remaining from the nation’s history of slavery and racial bias. Justice Marshall gave a clear signal that while legal discrimination had ended, there was more to be done to advance educational opportunity for blacks and to bridge the wide canyon of economic inequity between blacks and whites.

Marshall’s lifework, then, literally defined the movement of race relations through the century. He rejected King’s peaceful protest as rhetorical fluff, which accomplished no permanent change in society. And he rejected Malcolm X’s talk of violent revolution and a separate black nation as racist craziness in a multiracial society.

Instead Marshall was busy in the nation’s courtrooms, winning permanent changes in the rock-hard laws of segregation. He created a new legal landscape, where racial equality was an accepted principle. He worked in behalf of black Americans but built a structure of individual rights that became the cornerstone of protections for all Americans. Marshall’s triumphs led black people to speak of him in biblical terms of salvation: “He brought us the Constitution as a document like Moses brought his people the Ten Commandments,” the NAACP board member Juanita Jackson Mitchell once said.

The key to Marshall’s work was his conviction that integration — and only integration — would allow equal rights under the law to take hold. Once individual rights were accepted, in Marshall’s mind, blacks and whites could rise or fall based on their own ability.

Marshall’s deep faith in the power of racial integration came out of a middle-class black perspective in turn-of-the-century Baltimore. He was the child of an activist black community that had established its own schools and fought for equal rights from the time of the Civil War. His own family, of an interracial background, had been at the forefront of demands by Baltimore blacks for equal treatment. Out of that unique family and city was born Thurgood Marshall, the architect of American race relations in the twentieth century.

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X both died young, the victims of assassins. They became martyrs to the nation’s racial wars. Thurgood Marshall lived to be eighty-four and was no one’s martyr. Given that Marshall laid the foundation for today’s racial landscape, his grand design of how race relations best work makes his life story essential for anyone delving into the powder keg of America’s greatest problem.

He was truly an American Revolutionary.