Few episodes in the long, bloody chronicle of the subjugation of the Indian were more violent than the Pueblo uprising of 1680, the one completely successful revolt against the rule of the white man in American history.

-

June 1961

Volume12Issue4

Editor's Note: Few episodes in the long, bloody chronicle of the subjugation of the Indian were more violent than the Pueblo uprising of 1680. Organized and led by the mysterious medicine man, Popé, the New Mexico Indians drove an entire Spanish colony from their land- the one completely successful revolt against the rule of the white man in American history. The story of Popé and the struggle of his people Is taken from Alvln M. Josephy, Jr.’s book on great Indian chiefs.

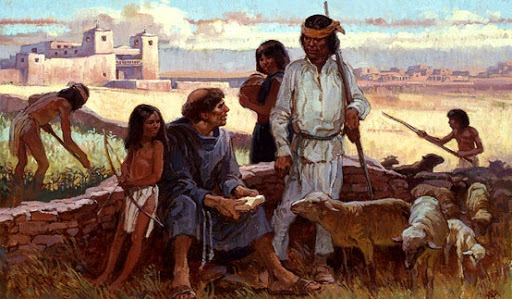

In the year 1598, two decades before the English Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, an expedition of several hundred Spanish colonists—led by Don Juan de Ofiate, and complete with eleven Franciscan friars, a herd of seven thousand bawling cattle, a column of helmeted troops in metal and leather armor, and a long, creaking line of supply carts—lumbered north across the burning deserts of Mexico to the fabled Rio Grande. On the banks of that river, on April 30, slightly south of the future townsite of El Paso, they paused in a sheltering grove of dusty cottonwoods, and before a cross and the royal standard of the king of Spain took possession “once, twice, and thrice,” of all the “lands, pueblos, cities, villas, of whatsoever nature now founded in the kingdom and province of New Mexico … and all its native Indians.”

For eighty-two years thereafter, in that remote and curtained part of the continent far beyond the horizon of the European colonies being created on the Atlantic seaboard, successive generations of Spanish governors, priests, troops, and settlers extended their reign over a beautiful but harsh wilderness of mesas, plateaus, and river valleys, forcing Indians to submit to the two majesties of church and state, and impressing thousands of them into a cruel encomienda system of serfdom. Then, suddenly, in 1680, it was all over. In one of the most dramatic uprisings in American Indian history, the oppressed natives struck furiously for their freedom. Streaming from pueblos and cornfields in every part of the province, they slew 400 Spaniards, drove 2,500 others in shock and terror back to Mexico, and in a few weeks swept their country clean of the white man’s rule.

Their stunning triumph, never again matched by natives in the New World, was organized and led by a shadowy Pueblo Indian medicine doctor called Popé, who is still little known to history. To the battered Spaniards, who spent the next twelve years trying to regain the province, defeat was humiliating enough. But it was added gall that an idolatrous medicine man, obviously an agent of the powers of darkness, had been the instrument by which the might and power of the Spanish Crown and the True Faith had been overthrown and chased in ignominious flight from the land.

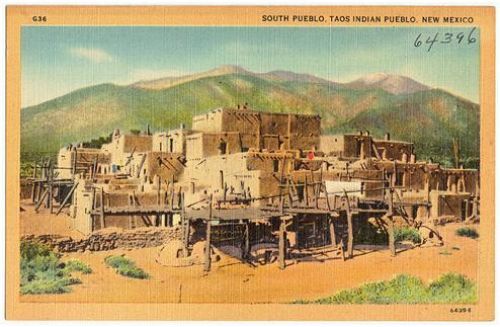

During their long rule, the Spaniards thought they had come to understand the Pueblo people. There were more than sixteen thousand of these Indians, occupying about seventy different sites, some widely separated, on the tops of steepwalled mesas and in the plains and valleys from present-day Arizona to the mountains east of the Rio Grande. Each settlement, originally something of an independent city-state, was gathered around a single communal hive of apartment-like rooms, made of adobe and joined together in a sprawling building that rose several stories high and looked like reddish-brown cubes set back on terraces, one above the other. Despite the similarity of their homes, not all the natives were alike in customs, backgrounds, or languages. In the chromatic, rocky desert of the West were Zunis and Hopis, and along the Rio Grande were Keres, Tewas, and others among whom the Spaniards settled, calling all of the Indians Pueblos (the word in Spanish means town, or village) for the city-like aspect of their terraced buildings.

All of them, as they sometimes demonstrated, could fight fiercely in defense of their homes, but generally they were a peaceful and mild-natured people, sometimes superstitious and troublesome to their Spanish masters, but more often docile and obedient. It was inconceivable to the conquerors that so pacific a subject nation, which had never waged a war of aggression against other Indians, would seriously rise against a colony of Spain, whose armies of conquistadors had crushed the empires of powerful caciques and sun gods everywhere south of the Rio Grande; and even as they fled back to the safety of Mexico after the revolt, the refugees from Santa Fe blamed it all on the single satanic instrument, Popé, who in some terrible way had been able to stir up the gentle Pueblos and under his spell “had made them crazy.”

Who Popé was in the secret and awesome scheme of native life, and how he had managed to arouse his people in such a sudden and concerted uprising throughout the province, was beyond the comprehension of the desperate Spaniards, who asked every friendly Indian along their escape road, “What was the reason for it?” Even when one old native, whom they dragged from his horse, told them that the Indians resented what the Spaniards had taken away from them—their ancestral ways of life and the right to their own beliefs—they thought he was bewitched. Like other white men in generations still to come, they shrugged off as savage stubbornness man’s longing to be free, and the patriotic motive behind the hatred and terror of Popé and his wildly screaming Indians eluded them entirely. The uprising was a simple struggle to restore the past, but the Spaniards could not understand it because they could not abide what had been.

Prior to the revolt, the Spanish authorities had hardly known Popé. He had been only one of many obscure medicine men who, despite the friars’ stern proscriptions of native beliefs, had continued to defy the white men with secret religious practices in the pueblos. After the uprising had occurred, the gulf between the Spaniards and the Indians kept them from learning much more, and when they were finally able to reconquer the New Mexican province Popé was dead, and other Indian leaders had taken his place. Under the new Spanish regime, the officials were anxious to eradicate the memory of the revolt and the idolator who had led it, and in time even the little that was known about Popé became hazy and uncertain in the white men’s chronicles of the province. Today, from the documents of the governors and priests, from contemporary declarations of settlers, soldiers, and witnesses of the events, and from a few frightened narratives of Indians who gave the Spanish leaders accounts of what had transpired on the native side, history can piece together more about him.

The roots of what ultimately occurred in 1680 reached far back in antiquity to the original forming of the Pueblo people’s beliefs and civilization. Their history began in the very dawn of the habitation of the New World by men. In days the Spaniards knew nothing about, thousands of years before, the earliest ancestors of the Pueblos had come down from the North, hunting mastodons, camels, and outsized bison with long spear-throwers called atlatls that hurled points of flaked stone into the animals. As the ancient beasts had become extinct, the people had gradually learned to gather fruit and roots; to plant corn, beans, and cotton; to weave cloth from fibers; and to settle down in pit houses and grass shelters. In time, other migrants and traders from more developed areas in Mexico and elsewhere settled among them and brought them new skills, and by approximately 700 A.D. , they had become accomplished potters and basketmakers. After 800 A.D. , they developed the beginnings of their modern pueblo buildings, fashioning one-storied mud structures of many rooms joined together, and turning their round, cistern-like pit houses into secret ceremonial chambers called kivas.

The first great Pueblo culture reached its peak between 1050 and 1300 A.D., when large numbers of people took to living together in many-tiered communal dwellings built in the open or in arched recesses part way up the steep walls of cliffs. In the valleys near the pueblos, the Indians tended their fields, practicing both dry-land and irrigation farming, and storing then-surplus crops in special rooms against times of drought and famine. All across the high plateauland, the people prospered.

In one of the great mysteries of prehistoric America, this first Pueblo era came to a sudden and unexplained end late in the thirteenth century. A devastating drought occurred in part of their country from 12761299 A.D., but neither it nor any other reason yet known fully accounts for a wholesale trek by all the Pueblo people, who abruptly abandoned the high plateau sites they had inhabited for centuries. Leaving their towns and buildings standing empty and silent, they moved south and eastward to mesa tops on the desert and to the Rio Grande Valley, where they established brand-new settlements in which the Spaniards later found them. There, in a new homeland, they continued their cultural rise, weaving legends and sacred beliefs around fast-receding memories of olden days, and endowing their civilization with endless cycles of colorful and mysterious rituals.

The philosophic base on which they constructed their society was a conviction, permeating all phases of their life, that everything they could possibly comprehend—the rocks and natural forces around them, the ideas in their heads, distances across the land, animals, birds, reptiles, every action, thought, and being in their consciousness—was part of a great living force and contained a spirit that existed everywhere; this spirit behaved alike in everything in which it dwelled. In their view of their own position in the world, moreover, whatever existed on earth came from an underworld to which it even tually returned in death. Passage between the two regions was through the waters of a lake; the first men had originally emerged in the world, bringing spirits with them from below, at a mysterious place in the north called Sipapu. Once on the earth, men thought of everything as radiating from central points of awareness—themselves, a family group, or an entire pueblo; and all beliefs were bound to Sipapu, where man had first entered the world, and which all communities constructed symbolically within their kivas. Such stone-lined pits in the center of their round ceremonial chambers were regarded as the actual passages between the lower world and the earth above, and the kiva, as a powerful and awesome symbol, was looked upon by the town as the place where the two worlds joined.

Since the people’s welfare and good fortune demanded harmonious attunement to the spirit world around them, Pueblo society was tightly knit and rigidly conformist. Most towns were headed by a single leader who served for life, and all the people under him were divided into cults and secret societies, each of which had its own duties and sacred kiva. Every cult, in turn, had a head man who was in charge of its ceremonial activities. Only men were allowed inside the kivas, which were sometimes underground but more often were built above ground like round towers and entered by ladders dropped to the interior from a hatch in the roof. Inside the chambers, the cult leaders kept their fetishes and other sacred objects, including brilliantly painted and feathered masks and costumes for kachina dances—group prayers in which the wearers of the masks believed they possessed the spirits and powers of the gods they impersonated.

At the times of such dances, the men of a cult disappeared into their kiva, and when they came crowding back up the ladder and over the roof, wearing their great masks, the people of the pueblo participated with them, certain that the gods had come to town from the sacred lake through the passageway in the kiva. The most important dance was that of the rain gods, the givers of life to the people of the desert, and there was no deception involved in their appearance because everyone, including the portrayers of the gods, understood that the masks actually conveyed their spirits. Nevertheless, the mysteries attending the arrival of the gods inside the kivas could not be witnessed by women or children.

Before the boys of a pueblo were nine years old, they were taken into the secret chambers and brought face to face with the masked kachinas, who proceeded to whip them furiously, trying to drive the badness out of them and prepare them for their important future roles. At adolescence, the boys were again given a lashing in the kivas, but this time the kachinas suddenly unmasked in front of them and, threatening quick punishment if they failed to keep the secret, showed them that after all it was the real men of the village who turned miraculously into gods when they put on the masks. After this terrifying initiation, the youths received long training in the rituals and secrets of the cult and, when they married, were finally ready to become kachinas themselves.

In addition to the cults, each pueblo’s secret societies were charged with specific community functions, such as the prosecution of defensive warfare, the hunting of game, the appointment of nonreligious officers, and the training of masked clowns who cavorted in the ceremonial dances and served as town disciplinarians Martians by raffishly ridiculing, censuring, or whipping those who had been guilty of offensive behavior. There were also important curing societies, composed of powerful doctors who kept watch over a pueblo for the evil spirits that brought sickness and death to their people. As recipients of the great knowledge of the medicine men of the spirit world, the doctors were believed able to recognize and do battle with witches that no one else could even see. They used their gifts to unmask the invisible evildoers, and with prayers, chants, and mystic paintings of colored corn meal, which they sprinkled on the ground in curative designs, worked hard to charm away the spirits and save their patients. The medicine men, of whom Popé was one, were the people’s daily guardians of life and health, and their unique position, constructed on centuries of faith, often gave them influence in political as well as medical matters.

Though possibly past their cultural peak, the people of the pueblos were suddenly faced in the sixteenth century by two developments that threatened their future. From the north there appeared dangerous Ute marauders and wandering bands of fierce Apache hunters, who had left their Athapascan relatives in Canada not long before and had migrated to the Southwest, where they began to harass the peaceful and productive towns of the Pueblos. Though their numbers and power gradually increased, the ultimate threat of these nonagricultural nomads was abruptly eclipsed by another invader who appeared without warning from the south and eventually cut short with finality all chance of further Pueblo development.

The discovery of the Pueblos by the Spaniards, though an inevitable consequence of their conquest of Mexico in 1521, stemmed from the reports of Cabeza de Vaca, who had wandered through the Southwest in the 1530’s ( see “The Ordeal of Cabeza de Vaca,” AMERICAN HERITAGE, December, 1960). His tales of fabulous new lands that lay just to the north of his route had fired the imaginations of the Spaniards, and in 1539, the first Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, selected a Franciscan, Fray Marcos de Niza, to reconnoiter the northern territory to discover if it was, indeed, another fabulously rich native kingdom, worthy of a new expedition of conquest.

Imbued with an enormous imagination of his own, Fray Marcos set off for the distant land, guided by Estevanico, the Moorish slave who had accompanied Cabeza. Estevanico traveled ahead of Fray Marcos and, accompanied by some loyal Indians of northern Mexico, reached an adobe pueblo of Zufiis at the base of a butte in the western desert of what is now New Mexico. Adorned with feathers and bells and taking seriously the character of a god with which the Indians had endowed him during his journey with Cabeza de Vaca, Estevanico sent to the Zuni chief a ceremonial gourd rattle he had picked up during his earlier wanderings. The Zuni, in a rage, recognized it as belonging to people who had been his enemies, and he apparently ordered Estevanico to leave the country. The Moor refused and instead sent back glowing reports to Fray Marcos, who was still following hard on his trail, that he had reached a wonderful city of a great and wealthy land called Cibola. It was his last report. Soon afterward, the survivors of his party came flying back to Fray Marcos with news that the Zunis had attacked them and slain the Moor with arrows.

The Franciscan hesitated, then with two Indians stole forward for a swift, secret look at the Zuni pueblo. From a distance, the terraced city seemed to confirm what he wanted to believe, and he hastened back to the Spanish settlements in Mexico, reporting that everything that Cabeza and Estevanico had said was true and that with his own eyes he had actually seen “house doors studded with jewels, the streets lined with the shops of silversmiths.” Moreover, he said, the Indians with Estevanico had told him that this was only the first and smallest of seven cities.

The friar’s news was what Viceroy Mendoza was waiting to hear, and the next year, 1540, he dispatched the young, hot-blooded governor of the North Mexican province of New Galicia, Francisco de Coronado, with an expedition of 230 mounted troops, 62 foot soldiers, a company of priests and assistants, and almost 1,000 friendly Indians to explore and seize the new territory of Cibola. Guided by Fray Marcos, the army of conquistadors followed a rough and difficult route northward across hot and waterless deserts and finally reached the Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh. The Spaniards were appalled to learn that the miserablelooking mud pile of ladders and adobe walls was Fray Marcos’ idea of a sumptuous city of gold and jewels, and the angry Coronado wrote to Mendoza that the “priest has not told the truth in a single thing he said.” But the army was starving after its long, wearying march, and at least there were Indian supplies of corn and beans stored in the pueblos.

At first, Coronado’s signs of peace were ignored by the frightened inhabitants, who were stunned by the sudden appearance of the strange host and its fantastic animals and equipment. For the first time the Indians were seeing horses, whose long heads and big teeth made the natives certain that they ate people. It was no reassurance to them, either, that the newcomers in shining helmets and suits of armor sat unconcernedly on the snorting beasts, and the alarmed Zunis made a line of sacred corn meal on the ground and warned the Spaniards not to cross over it with their animals. When the invaders ignored the warning and started forward, the panicky Indians sounded their war horn and let fly a hail of arrows. The sudden answering explosions of Spanish guns and the fierce charge of horses and men with long lances routed the natives, who fled to their pueblo, and the battle was quickly over. While the Spaniards broke into the Zunis’ stores and appeased their hunger, the defeated Indians sent runners to other pueblos with amazing tales of the power of the newcomers, and chiefs from other towns soon arrived with gifts for what the Indians began to suspect were the white gods who, ancient legends had dimly suggested, would some day appear among them from the south.

Moving to the Rio Grande country which the Indians called Tiguex, the Spaniards established winter headquarters in the pueblo of Alcanfor and ordered all the Indians to evacuate it. Abuse of native women and brutality toward several chiefs brought matters to a head, and before Christmas, revolt flared in some of the settlements, whose outraged inhabitants were now sure that the newcomers were mortals like themselves. For more than three months, the Spaniards faced resentment and hostility, and again and again, with wild battle cries of “Santiago,” launched furious assaults against the walls of defiant cities, cutting down their defenders by the hundreds and burning captured Indians at the stake. Abominable cruelties and atrocities mounted on both sides, until at length the chastened Tiguas of the area abandoned their villages and stole away to other pueblos in the north.

In the spring, with authority established over the region, the Spaniards re-formed their ranks for another long march. Leaving the silent Indian towns, they headed for the northeastern plains, where brandnew rumors hinted of a province called Quivira, whose lord “took his afternoon nap under a great tree on which were hung a number of little gold bells, which put him to sleep as they swung in the air,” and where “everyone had their ordinary dishes of wrought plate, and the jugs and bowls were made of gold.” It was another will-o’-the-wisp. When Coronado reached Quivira on the plains of Kansas and found it to be an impoverished settlement of grass huts belonging to Wichita Indians, he had had enough. His army returned to another bitter and profitless winter in the empty pueblos of Tiguex. In the spring, with all their high hopes of two years before turned to frustration and disillusionment, they abandoned the Rio Grande and straggled gloomily back to Mexico.

Their unhappy reports discouraged further Spanish interest in the northern country, where it was now proved that there was neither gold nor other treasure, and for almost forty years the Pueblos saw no more of white men. Gradually, the Indians came back to their Tiguex settlements, filled with bitter memories of the invaders. Coronado, however, had had no idea of establishing a colony among them, and the Span iards had created no lasting damage to the Pueblos’ civilization. Once again, the Indians were masters of their homeland, leading the centuries-old lives of their ancestors, and as time went on, the wounds of their first contacts with the Spaniards were overshadowed by a growing desire for the metal tools and other goods of the white man’s civilization that Coronado’s men had brought among them.

In the south, meanwhile, a new generation of Spaniards began to talk again of the strange lands and peoples whom Coronado had visited. There were rumors of rich mines that the conquistadors had missed, and fortunes to be made in Tiguex and in the mysterious countries that lay beyond the Rio Grande. New Spain was still filled with adventurers, restless to repeat the glorious triumphs of Cortes and Pizarro, and by 1580 eager petitioners were again asking the king of Spain for permission to bring the northern countries under Spanish domination and convert the natives who lived in the terraced cities in those regions.

The latter aim, a holy one, though a cover for personal greed, was more immediately appealing to the authorities, and in July, 1581, three Franciscan friars, accompanied by nine soldiers and sixteen Mexican servants, traveled back to Tiguex along the newly discovered Conchos River route that led from northern Mexico to the Rio Grande. The Pueblos received the new white men without enmity, eyeing their goats and horses and packs full of trade goods, and allowing them to move freely through their country. One of the priests resolved to return to Mexico alone to report what he had seen, and the rest of the party explored east and west, visiting the different pueblos and coming again upon the Zunis. Returning at length to the Rio Grande, the other two priests and several of the Mexicans decided to settle among the Indians and try to convert them to Christianity, and the rest of the group headed back to Mexico.

The following year, another missionary party rode north to Tiguex and, arriving among the Pueblos, found to their horror that all three of the priests who had entered the country the previous year were dead. The Indians, it appeared, had slain them for their possessions and trade goods. After fighting several battles with the Pueblos, the members of the new group returned to Mexico with romantic tales of what had happened to them, but the stories they told only served to quicken interest in the region. Impatient adventurers, still waiting for permission to lead official expeditions to what was now being called the province of New Mexico, were sure that they could conquer the unruly inhabitants of the north for cross and crown, and incidentally find fame and riches for themselves.

Finally, in 1590, one of them, Caspar Castano de Sosa, lieutenant governor of the province of Nuevo Leon, without waiting for word from Spain, organized a colonizing expedition of 170 people, equipped it with two brass cannons and a long train of supply carts, and started off for Tiguex. The group reached the Pueblos without serious difficulties and established a camp near an Indian town that was later called Santo Domingo. The Indians watched the new arrivals sullenly, giving them food when they asked for it, but otherwise having little to do with them. After sending a message to the viceroy in Mexico City announcing his success in establishing a colony, Castano de Sosa went off exploring the countryside. Soon after his return to the Rio Grande, he heard that a party of Spanish troops was marching up the river to Tiguex. Thinking that they were reinforcements for his people, he went out to meet them and was promptly arrested for presuming to erect a colony in New Mexico without royal permission. The soldiers dispersed the settlement, and the people gradually made their way back to Mexico. In the capital, Castano was tried, convicted, and exiled to China, where he was later killed. Other men secretly, and without success, continued after him, trying to steal into the country of the Pueblos, but eight years after Castano’s short-lived colony, the Spanish court finally authorized the scion of one of the wealthiest families in Mexico, Don Juan de Oñate, son of a governor and husband of a granddaughter of Cortés, to occupy the land of the Pueblos for the king and establish a permanent frontier settlement in the province. Onate, a vigorous and capable man in middle life, was a worthy successor to the long line of ambitious conquistadors who had preceded him. Spending a fortune of his own, which he fully expected would be repaid with dividends by the still undiscovered riches of New Mexico, he organized a huge expedition and in 1598 led it north to the Rio Grande. Marching under clear, brilliant skies, he reached the first of the pueblos on June 24. As he moved from one town to another, the size of his force awed the natives, and chiefs came forward solemnly to offer friendship and, at the direction of the governor and his host of Franciscan friars, to pledge allegiance to the king of Spain and to his Christian religion.

At the pueblos of Unquiet and Unique near the juncture of the Chapman River and the Rio Grande, Donate halted and, like Coronado before him, told the natives to evacuate one of the towns for his men. The Indians moved out peaceably, and the Spaniards renamed the village San Juan and designated it as the capital of the new colony. Irrigation works were begun and a church built, and on September 8, the first mass was sung in the new building. The Spaniards had invited the heads of all the pueblos to witness the colorful ritual of the Catholic religion, and the next day Donate assembled the chiefs again, once more pledged them to be loyal to the Spanish king, whom he represented, and then, through the Father President of the friars, proposed to them that they and their people receive the great joys and benefits of the true faith by accepting the white man’s God.

The chiefs were confused, but after discussing it among themselves agreed to allow the newcomers’ priests to come and visit them in their pueblos and instruct their people, with the understanding, however, that if the Indians approved of what they learned, they would adopt the Spaniards’ teachings, but if they did not like it, they would not be forced to accept what they heard. It was good enough for Donate and the friars, who divided the pueblos among themselves and departed for the lonely mission work at the different villages. Meanwhile, with his mind on material rewards, Donate was restless to find the riches that Coronado had missed, and on October 6 he rode out of San Juan at the head of an exploring party. While he was gone, the priests erected crosses at the different villages and began their work of telling the natives about Christ and the religion of the white men. Their work was suddenly interrupted by an outbreak of resistance that occurred at the sky city of Tacoma and almost threatened the future of the entire colony. A body of Spanish troops, marching westward one day, sighted the pueblo perched 400 feet above them on a steep-walled mesa. Faced by a shortage of food, the men followed a path up the high, rocky cliffs and entered the adobe town. At first, the Indians seemed peaceful, and the Spaniards broke into small groups and poked through the different apartments. What offense they gave the natives is not known, but suddenly a war cry rose through the village, and angry Indians came pouring out of holes in every rooftop, ready for battle.

The small band of Spaniards tried to gather in one of the streets, but in a moment, a screaming mob of almost one thousand natives, firing arrows and swinging clubs and lances, came at them from every side and cut them off. The wild combat lasted for three hours, and most of the Spaniards were hacked to pieces. Several of them managed to escape down the sides of the mesa, while others jumped to their deaths from the cliffs. Four of the soldiers miraculously survived the 400-foot fall, landing in sand banks at the base of the mesa, and with the other survivors got back to San Juan with news of the catastrophe. Wondering if all the other pueblos would now turn on them, the fearful colonists set a twenty-four-hour watch and dispatched messengers to the isolated priests, warning them to abandon their lonely missions and hasten back to the capital.

Shortly before Christmas, Donate returned home, disillusioned at having found nothing but a harsh and empty wilderness, and aroused by the sudden threat to the future of his colony. Determined to punish the offending Indians, and by a swift and terrible example frighten any other pueblos that might be planning a challenge to his authority, he proclaimed “war by blood and fire” against Acoma, and sent a force of seventy men, heavily armed with hand weapons and two cannons, against the people of the mesa-top city. Reaching their goal, the avenging troops divided their forces, a part of them pretending to attack up one side of the cliff, while another stole unobserved up the opposite side.

The battle raged fiercely for three days, and at last the Spaniards got their whole force on top of the mesa and dragged their cannons into position against the pueblo. Loading the guns with two hundred balls apiece, they fired them point-blank into the natives’ ranks, piling up masses of Indian dead and wounded. Other soldiers set fire to the pueblos, and in the confusion and smoke of their burning village, the Indians gradually gave up the fight, throwing themselves from the cliffs or retreating to their fiery apartments to hang themselves. Almost a thousand Indians perished in the fight, and the Spaniards dragged a host of burned and wounded prisoners back with them to San Juan. Two of the captives managed to cheat their conquerors. In the Spanish capital they fastened nooses around their necks in a gesture that awed the colonists, and scrambling to the top of a tree, cried bitterly to the Spaniards, “Our towns, our things, our lands are yours,” and hanged themselves. The other prisoners were not so fortunate. The Spaniards herded them into a mock trial that found them guilty, then cut off the hands and feet of many of the adult male captives, and sentenced the women to “personal service” in the colony, a polite term for slavery.

Soon afterward, the Spaniards sacked two more pueblos that made a show of resistance, killing nine hundred Indians in one of them and returning to San Juan with a string of two hundred more captives whom they tortured or sentenced to slavery. At length, the savage destruction of the native villages and the harsh fate of the defenders cowed the rest of the pueblos, as Onate intended, and peace, enforced by Spanish arms, settled over the Rio Grande Valley, lasting uneasily under the oppressor’s hand for more than eighty years.

The governors who succeeded Onate abandoned all hope of finding treasure cities in the province, and, establishing a permanent Spanish capital city which they built of adobe in 1610 and called Santa Fe, they turned their energies to grinding profits from the only source of wealth available to them in the country, the enforced labor of the subjugated natives. To favored men around them, the governors granted encomiendas , bodies of land that they seized from the Indians, and to which they bound the native inhabitants as serfs. In addition, they ordered every native in each pueblo to pay annual tributes of cloth, maize, and personal labor to the colony, and Indians were soon working the white men’s fields, tending their goats and cattle, and manufacturing, as slave laborers, cotton shirts and numerous articles of cloth, wood, and hides which the colonists sold for themselves in the markets of Mexico.

The most relentless exploiter was the governor himself, who used his autocratic powers to amass a personal fortune before his term in office ended. With the help of a retinue of spies and assistants who encouraged graft and corruption on every hand, he demanded a share of each encomendero ’s profits, imported goods from Mexico which he forced Indians and colonists alike to buy from him at high prices, and sent back to the south long pack trains of Indianmade products which his agents sold for his personal account.

When they were not working for the governor and settlers, the natives were busy paying tribute in goods and services to the Franciscan friars whom they were forced to accept and support in their pueblos. Guarded by soldiers, the priests had courageously returned to the villages after the Acoma revolt and had stood with their wooden crosses among the Indians, preaching boldly to them about Christ. Gradually, their dedication and bravery stirred the Pueblos and gained respect and safety for them, and as the Indians moved closer about them and listened with hushed attention to their dramatic tales and heavenly promises, the friars’ faith seized the natives’ imaginations.

Despite the angry opposition of the medicine doctors, large numbers of Pueblos knelt for conversion in the sunlight, accepting, with more curiosity and expectancy than understanding, the strange ideas and rituals of the white men, and in time grafting them onto their own ancient beliefs and ceremonies in a bizarre mixture of Christianity and spirit worship. As the priest became one with his converts, the natives eagerly accepted everything else he taught them, using the new tools he gave them, learning music, crafts, and Spanish methods of agriculture, and feeling strength and pride in their new knowledge and possessions. Eventually, at the edge of each pueblo, they helped the friars rear a village church, fitting for the awesome processions, ceremonies, and worship of their new faith and symbolic of the power and wealth of their new life.

With the passage of time, reinforcements from Mexico increased the size of the Spanish colony, and the conquerors’ hold over the Indians, aided by the supervisory offices of the friars in the pueblos, gave the conquerors an illusion of security. The entire economy of the valley rested on the exploitation of the natives, who were not allowed to ride horses or use firearms, and the uncomplaining fashion in which the gentle Pueblos responded to demands for labor and tribute made it seem that they, like the Indians of the Caribbean and Mexico, were thoroughly subjugated. From a number of directions, however, disaster was looming for the Spaniards. Many Indians were still unconverted, and even among those who were called Christians, the white man’s religion had often not penetrated far below the surface. The friars banned the kachina dances wherever they felt strong enough to do so, but it was another thing to drive a centuries-old faith out of people’s minds and hearts. In the recesses of the pueblos, the cult leaders kept alive old ways, telling the people that the kachinas were still in the kivas, and even the converted Indians still called on their medicine men, who smouldered with deep resentments over the presence of the friars.

The white men, too, did not help their own cause. An increasing drive for profits led to greater pressures on the Indians, and conflict broke out over policies that would have rushed the natives into total slavery and doomed them to extinction. Many of the Spaniards seriously believed that Indians were animals rather than rational humans, for unlike civilized men, they seemed indifferent to the ambitions and desires of thinking persons, had no greed for such things as jewels and gold, and appeared content simply to eat and sleep. Despite the fact that, in their own way, the friars too were instruments of native suppression, demanding faith and obedience from the Pueblos and undermining their powers to resist the lay conquerors, they could not, at least, agree that Indians did not possess souls, and their protection of their charges against excessive exploitation brought them into conflict with the lay officials.

Though other factors broadened the struggle, the question of whether the governor or the Franciscans had ultimate authority over the Indians divided the colony into two camps and rocked it with turmoil that grew worse under each succeeding governor. From the adobe palace in Santa Fe, the governors issued orders to the Indians, which the priests in the pueblos promptly countermanded. The governors flew into rages of jealousy and pettiness, sometimes spitefully urging the Indians to put on public kachina dances to defy their friars and at other times sending troops to invade the sanctity of churches and arrest the priests. The latter retaliated with fury of their own, condemning the governors as corrupt heretics and sending frightened squads of soldiers to seize the rulers for crimes against the Church.

Still the Spaniards continued to fight among themselves, and as the confusion worsened, their authority over the Indians was undermined. Many of the converted Pueblos were appalled by the hostility with which the white rulers treated their own priests, and their respect for the brown-robed friars waned sharply. During the second half of the seventeenth century, new difficulties suddenly struck the people of the villages, and for the first time in many years they began to wonder if they had offended their ancient gods. Beginning in 1660, serious droughts settled over the Southwest, bringing famine and disease with them. In one year, it was recorded, starvation was so bad that people were forced to eat hides and cart straps.

As the Pueblos suffered, their troubles were increased by bands of hungry Apaches, who could find no food on the plains and launched desperate raids against the agricultural settlements for supplies. Fighting hunger and sickness themselves and forced to defend their towns against the fierce attacks, the Pueblos became certain that they had displeased their gods, and in the dark kivas and mud-walled rooms the cult leaders and medicine doctors raised their voices with mounting boldness against the friars, urging their people to return to the ways of their ancestors before it was too late.

At this juncture, the fierce and mysterious figure of Popé suddenly appears in the reports of Spanish authorities. Popé was an old but vigorous Tewa medicine doctor in the San Juan pueblo. There is no record of his exact age, but it is apparent that all his life he had resisted the Christian religion and had struggled bitterly to keep alive the traditional Indian beliefs among his people. Again and again the Spaniards had denied him the right to conduct his rituals and finally, as punishment for his stubbornness, had seized and enslaved his older brother. The act had only enraged Popé further, and gradually he had become a symbol of uncompromising hostility to the conquerors.

With the coming of the drought, his religious activities began to take on political coloring. He held secret meetings in the pueblo and told the people that the gods were speaking against the friars, that the Spaniards must leave the land of the Indians. In time his audiences grew larger, and his influence spread, and soon word of his new activities reached the mayor of Santa Fe, who twice had him arrested and flogged.

It did the Spaniards little good. Popé’s warnings were already being repeated in pueblos throughout New Mexico, and the flames of the fight for religious liberty that he had started were setting fires in Indian towns everywhere. In alarm, the Spanish governor ordered his troops to visit all the settlements, halt the renewal of Indian dances and rituals, and arrest as many of the medicine doctors as possible. Forty-seven native leaders, including the furious Popé, were seized in the drive, and dragged into Santa Fe, where they were charged with witchcraft and sorcery. Three of the doctors were hanged as examples, and Popé and the rest were whipped and jailed.

The Governor’s action made matters worse for the Spaniards. Without their doctors, the people in the pueblos believed that they were defenseless against the invisible powers of evil that brought sickness and death to them, and from town to town native runners carried appeals for united action. At length, a determined delegation of seventy Christianized Indians from the Tewa pueblos on the Rio Grande marched on the Governor in Santa Fe and announced that unless the prisoners were turned over to them by sundown, the Indians would rise in revolt throughout the provinces and kill every Spaniard in New Mexico. The Governor consulted his advisers, and after anxious deliberation, decided that the natives were in dead earnest and that the colonists in New Mexico, who numbered about 2,800, could not hope to defend themselves for long against some 16,000 Indians. Reluctantly, he freed the doctors.

Hate and anger had spread everywhere now, and the fact that the Governor had shown weakness when threatened with revolt was not lost on the Indians. But Spanish authority was still strong, and most of the people were mortally afraid of the friars and their spies and soldiers, who still demanded obedience and inflicted stern punishments on offenders. In Santa Fe, the natives had won an opening skirmish, and the momentum of events was on their side, but if a revolt were to come, it would require more than hate in men’s hearts. To Popé, the bruised and smouldering medicine man, the time had come for Indian organization, leadership, and a magical spark with which to set the country aflame; and he moved quickly to provide his people with all three.

Traveling to the different pueblos, he held secret meetings with other medicine doctors and chiefs and soon won their loyalty to his plans. Their first duty, he impressed upon them, was to strengthen the courage of the Indians by cleansing their ranks of informers. As an example, he dramatically announced at one meeting in San Juan that he suspected his own son-inlaw, Nicolas Bua, the Spanish-supported Indian governor of the pueblo, of being a spy for the white men. The accusation had its desired result. The next day, the Indians stoned Bua to death in a cornfield, and though Popé had to flee from San Juan and hide in the kiva at the Taos pueblo to evade Spanish questioners, news of the incident spread rapidly among the towns and frightened the natives who had been acting as informers for the priests.

In the Taos kiva, Popé continued to meet with other chiefs and prepare plans for a general revolt. In the midsummer of 1680, he decided that the time for action had come and summoned his principal followers to him. To battle the Christians, he called upon the mystic powers that he possessed through his close relationship with the spirit world and before the eyes of his entranced audience, conjured up in the gloomy ceremonial chamber the wrathful spirits of native gods.

In feathers and shining paint, the gods breathed fire from every extremity of their bodies and announced that they were working for a revolt of the Pueblos. They had been sent to warn the Indians, they said, that the time was ripe for killing all the Spaniards and ridding the land of the oppressors, and as the chiefs listened to them in dread silence, they commanded Popé to set the date of the uprising and to send to each pueblo a cord of maguey fibers with a number of knots tied to it to signify the days left before the revolt.

The news of what had transpired in the secret chamber spread wildly among the people, and Popé dispatched his knotted maguey cords to the excited villages, calling for a concerted uprising on August 11, 1680, but slyly sending a later date, August 13, to several Christian chiefs whose loyalty he questioned. As he suspected, informers soon revealed the wrong date to the Spanish friars and notified them that old men in pueblos in the north were plotting a revolt after having received a letter from a lieutenant of their war god. The lieutenant, they told the priests, “was very tall, black, and had very large yellow eyes, and everyone feared him greatly.” This might have been a description of Popé himself: at any rate, on August 9, priests from three towns sent hurried word to Governor Antonio de Otermin in Santa Fe that “the Christian Indians of this kingdom are convoked, allied and confederated for the purpose of rebelling, abandoning obedience to the Crown and apostatizing from the Holy Faith. They plan to kill the priests, and all the Spaniards—even women and children—thus to destroy the total population of this kingdom. They are to execute this treason and uprising on the igth of the current month.”

The Governor immediately dispatched warnings to the Spanish officials at every pueblo and ordered the arrest of all suspected ringleaders. His warnings were too late. At seven o’clock the next morning, a panicked soldier came galloping into Santa Fe with news that the Indians at the nearby Tesuque pueblo had painted themselves for war, had killed the priest and a resident white trader, and were marching to join the natives at San Juan, armed for battle with bows, arrows, lances, and shields. The Governor ordered every Spaniard in Santa Fe to gather in the public buildings and sent soldiers scurrying through the countryside to round up whites who were out attending their fields and cattle. Setting a guard around the capital, he distributed arms to everyone capable of bearing them and waited for further news. It was not long in coming. During the afternoon, reports came in of uprisings in Taos, Santa Clara, Picuris, Santa Cruz, and other pueblos. Frightened soldiers rode back with tales of dead Spanish ranchers in the fields, smoking buildings, and armed Indians moving across the hills.

For the next three nights there was little sleep in Santa Fe, as the Spaniards waited for an Indian attack on their capital. In the surrounding country, the news grew steadily worse. Pecos, Galisteo, San Cristobal, San Marcos, La Cienega, Popuaque, and other pueblos had all joined the revolt, and reconnoitering squads of soldiers reported a growing trail of bloodshed and horror against isolated Spaniards who had been caught in their haciendas and estancias. On August 14, news came that a war party of five hundred Indians was finally marching on Santa Fe, and the next day small groups of them began to be seen moving through the cornfields around the city. More and more of them appeared, and as they pressed closer, filtering into the abandoned homes of Mexican Indians on the edges of the town, they called insultingly across to the defenders and danced defiantly on the rooftops of the flat adobe buildings.

Among the thousand Spaniards gathered in Santa Fe, no more than fifty were regular troops, and most of them were convicts conscripted in Mexico. But every able-bodied man was armed, and the Governor was confident that a determined attack by the Spaniards would scatter the Indian host and end the uprising. He tried first to negotiate with the natives, sending an escort of soldiers to provide safe conduct to the palace for one of the Indian leaders whom he recognized. The peace effort failed, and the next morning the soldiers attacked, attempting to dislodge the Indians from their threatening positions. The natives had never been allowed to use guns or own horses, but many of them were now supplied with both, and a furious fight lasted all day. By nightfall, however, the Indians had been pushed out of the fields and were fleeing to the foothills. Their flight was halted by the arrival of large reinforcements from San Juan, Taos, and Picuris, probably under Popé himself, and at dawn the Spanish capital was again under siege.

There was silence for two days as the Indians built up their strength. Then, on August 16, 2,500 natives charged at daybreak, sweeping out of the fields in huge masses that carried across homes and roads and broke over the ditch that supplied the Spaniards with water. Groups of Spaniards tried to regain the ditch but failed, and at noon the Indians swarmed around the walls of the palace itself, trying to burn the chapel at one end of the building. The entire garrison poured into the plaza to save the structure, and hand-to-hand fighting raged all afternoon. By darkness, the defenders had temporarily pushed the Indians back and barricaded themselves once more in the palace, which was now without water.

The next day, the battle began again. The desperate Spaniards, many of whom were wounded, had had a miserable night without water, but they met the attackers fiercely and in a number of sorties tried again to recapture the water ditch. Thrown back under a hail of arrows, stones, and gunshots, they almost lost the brass cannons that guarded the palace gates. They pulled the guns into the building’s patio with them, but had to fight off Indians all night, listening to native victory songs and watching the entire city of Santa Fe burn around them. Their anguish was increased by the groans of women and children for water, and at dawn, in a last savage attempt to drive off the natives, the garrison sallied out and took the Indians by surprise. The fighting was as bitter and fanatic as before, but fortune now favored the Spaniards, and after severe battling through the ruined town, the Indians finally abandoned the struggle and scattered into the hills, leaving behind three hundred dead and fortyseven prisoners.

Despite their victory, the shaken defenders were in no mood to remain in Santa Fe. The thirsty people gulped water, executed the Indian prisoners, and on August 21 began an exodus to the south, hoping to find safety in Spanish colonies lower down on the Rio Grande. Their hopes were dashed. Pueblo after pueblo stood emptied of Indians who had joined the revolt, and everywhere were only dead Spaniards and burned ranches. Carrying what small property they had been able to salvage, the long line of refugees reached El Paso, where they were finally able to rest in safety among friendly Manso Indians.

Behind them, the entire province of New Mexico was again in Pueblo hands. The native reconquest of the country had been complete. Some four hundred Spaniards had been killed, including twenty-one of the thirty-three Franciscan friars in the territory. Popé and his followers moved into the ruins of Santa Fe and after dividing the Spanish spoils, ordered the people to forget everything they had learned from the Spaniards and return to the ways of their ancestors. In each pueblo, the cult leaders conducted ceremonies in which the Christianized natives were washed clean of their baptisms with yucca suds. The use of both the Spanish language and Christian names was banned. Every object and relic of the Spanish days was ordered destroyed, and in 1681, the year after the revolt, the atmosphere was so changed that, from reports he received in his place of refuge, Fray Francisco de Ayeta, Commissary General of the Franciscan province of New Mexico, wrote that the Indians “have been found to be so pleased with liberty of conscience and so attached to the belief in the worship of Satan that up to the present not a sign has been visible of their ever having been Christians.”

And yet the Pueblo victory soon crumbled from within and turned to ashes. The people’s attempt to return to a manner of life that had existed before the coming of the white men proved impossible. With their oppression, the Spaniards had brought the material goods and culture of a higher civilization, and the natives could not easily abandon things which now seemed to them useful and desirable. Gradually, they began to oppose Popé’s stern injunctions, and he retaliated with executions and harsh punishments. Inevitably, he turned into a tyrant who even affected the hated ways of the conquerors whom he had ousted.

The records of his reign are scanty and rest almost wholly on testimony given to the Spaniards in later days by reconquered natives. But in the main, they each tell the same story. To show his power, Popé took to posturing like the Spanish governors before him, demanding that others bow in his presence, using prisoners as servants, and even riding about Santa Fe in the Spanish governor’s rattletrap carriage of state. In time, other problems beset the harassed people. Apaches showed up, stronger and more belligerent than ever, and without the Spaniards to help protect them, the Pueblos proved no match for the raiders. The Apaches laid siege to the towns, killed the Pueblos in their fields, and finally entered the defenseless villages at will, demanding tribute of maize, cotton cloth, horses, cattle, and Pueblo women. Their seizure of horses led to a revolutionary development among the Indian tribes west of the Mississippi River, for up to that time no natives in that part of the continent had possessed horses, and few of them had ever seen one of them. Now the Apaches spread them across the plains and into the Rocky Mountains, and tribe after tribe came into possession of them for the first time.

A few years after his triumphal revolt, Popé died. Like many revolutionists, he had successfully led his people in a popular cause, only to betray them. The despotism of his reign helped to cloud his memory and left to history the image of an autocratic fanatic. But it could not obscure the original patriotic motives of his uprising, nor the fact that for a brief moment he freed his people from the oppression of a foreign conqueror. After his death, the lot of the Pueblos continued to deteriorate. The unity among the different cities that Popé had formed collapsed amid rivalries and quarrels. The Apache raids increased, and in 1692 when a Spanish army under Diego de Vargas finally marched north again from El Paso, the country of the Pueblos offered little resistance. With the troops came new governors, friars, and colonists, and in time, no sign showed in the hot sun of the arid country that the Pueblos had ever fought for, and won, their right to be free.