The daughter of a Gaelic-speaking fisherman on a remote Scottish island emigrated to New York, worked as a maid in the Carnegie Mansion, and married Fred Trump. Her son would become President.

-

September 2020

Volume65Issue5

Editor's Note: Nina Burleigh was National Political Correspondent for Newsweek and has written for numerous publications including Time, The New York Times, New Yorker, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. She is the author of seven books including a biography of James Smithson, The Stranger and the Statesman. Portions of this essay appeared in her most recent book, The Trump Women: Part of the Deal, about the women who have had the most profound influence on President Trump's life (formerly published as Golden Handcuffs: The Secret History of Trump's Women by Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster).

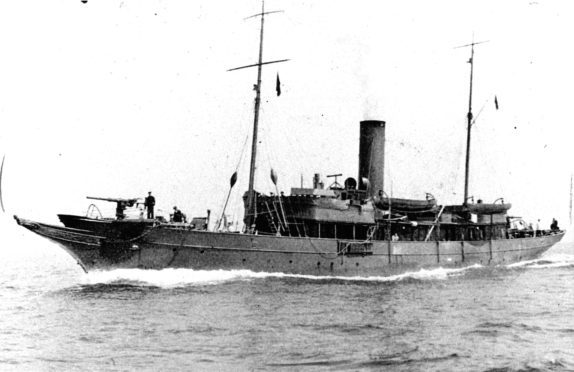

Mary Anne MacLeod was the tenth and last child born to a fisherman and his wife, on May 10, 1912, in the tiny town of Tong on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. She was just a wee thing, as the islanders would say, only seven years old, when a catastrophe struck that would mark her people and her generation. Two hundred of the island’s finest young men drowned in the wreck of HMY Iolaire within sight of the village. The ship was bringing veterans home from World War I when it struck rocks in a storm early in the morning on New Year's Day and sank. The poor men who had survived years of combat died within sight of the harbor lights.

The tragedy was probably one of Mary's earliest memories. In the way that history shapes individuals, who then unwittingly shape history themselves, the disaster was a catalyst that ultimately sent the girl who would give birth to a president far away from her home.

The Isle of Lewis, a windblown speck of rock and peat at the northerly edge of the Hebrides, had been controlled by local clan chiefs, the MacLeods, MacDonalds, Mackenzies, and MacNeils. In the nineteenth century, the English and their allies the landed Scottish lords instituted a brutal policy called the Highland Clearances, expelling peasants from farms and communities all over northern Scotland in order to empty the land for sport hunting and sheep grazing. Crofters, who had lived for centuries on the land, eking out a bare subsistence from the rocky soil by constructing “lazy beds” on which to grow potatoes and other crops that could withstand the fierce and ever-changing weather, lost everything.

Genealogists believe that Mary Anne MacLeod’s ancestors were among the poor farmers kicked off their plots by the landowners, and forced to live for generations in destitution in the small towns to which they had migrated seeking food, shelter, and work. Her branch of the MacLeod family had remained on Lewis through the hard years of the 1800s, while tens of thousands of mainland Scots and Hebrideans, facing starvation, emigrated to Canada — some under threat of force.

When Mary Anne was born, the remaining islanders maintained ancient traditions, crofting as tenants, fishing on all but the stormiest of days, and speaking Gaelic at church and school even as the English overlords discouraged it.

Mary Anne was born in a croft house, which her father had owned since 1895. The two-bedroom house had been converted from an ancient and indigenous island “blackhouse” — constructed of stone and with a thatched roof, which let smoke from the open peat fire seep out without need of a chimney. Ten siblings, the two MacLeod parents, and probably some grandparents, all shared the cottage.

Mary Anne learned speech, songs, and psalms in a Gaelic-speaking household. When she was old enough, she studied English, her second language, along with other fishing and crofting children at the little Tong school. On an American immigration form, Mary Anne reported that she was educated to the equivalent of America’s eighth grade, meaning she left school at around age thirteen or fourteen, presumably to work on the croft or in some other job to help boost the family income.

The Isle of Lewis was and still is deeply religious, and at the time it was experiencing a series of hard-core revivals with a tinge of popular rebellion against the establishment. Church was serious business. Women and men both wore black to services, and four Sunday services made the Sabbath a daylong affair.

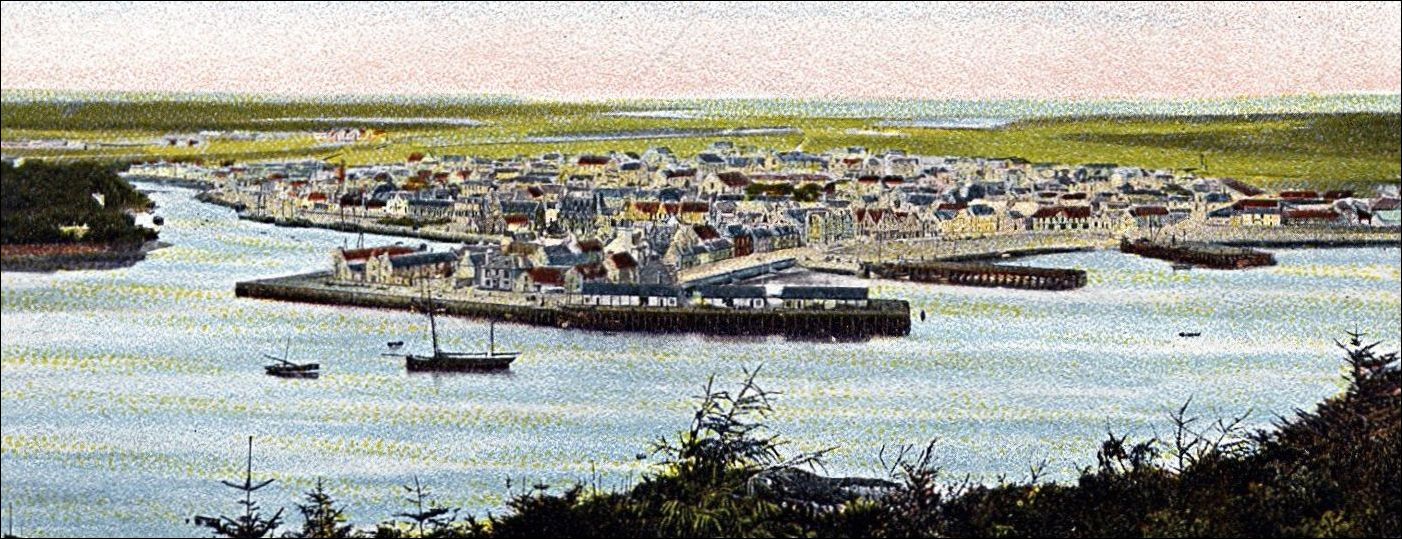

The MacLeod family belonged to the Scottish Free Church, a relatively more conservative congregation, in the nearby town of Stornoway. The dignified gray stone structure was planted on the gentry’s street, Matheson Road, lined with handsome brick mansions built by and for the families of the local merchants and wealthier landowners. To distinguish the residents of Matheson Road from the rest of sheep-and fish-smelling islanders, in their muck boots and oilers, the town forbade the poor from walking on the street.

The ban would have included the fishing MacLeods.

The MacLeods lived on the edge of what the locals called “the saltings,” a several-miles-square tidal flat between the hamlet of Tong and the larger town, that at certain times of the day turned into quicksand as the tide rose. To get to church, the family would pick its way across the flat in muck boots—a perilous journey that only the fishing families who lived on its edges would attempt. Even with their knowledge of the safest route, people were regularly lost.

As a girl growing up in Tong, Mary Anne had a single example of a more opulent way of life, in the gray, three-story Tudoresque Lews Castle, perched on a hill across a tidal inlet from the main harbor. Built in the mid-1800s by the same Matheson after whom the high road was named, the turreted and perfectly intact castle was surrounded by sprawling manicured woods and a great green lawn, all of it long since scraped free of peat-smelling crofters and their sheep. From any point along the harbor, the little girl could look across the muddy inlet and up at the crenellated turrets and beveled, jewel-like windows, portholes into a life of elegance, wealth, and ease.

After the clearances, the First World War devastated the community’s population. The Isle of Lewis and the fishing town of Tong were a long way from the trenches of the Great War, but they gave a higher percentage of young men to the effort than most places, having been promised they would get land in return for men. (When the owners did not keep that promise, Lewis men rebelled, and won back their crofts.)

The island’s surviving soldiers were further decimated by the shipwreck in which more than two hundred of them returning from the war drowned on New Year’s night 1919, during a storm and within sight of Stornoway. The captain and the soldiers had been celebrating and drinking, and failed to notice the harbor rocks until it was too late.

Because of war and that disaster, by the time Mary Anne was old enough to notice boys, the women of Tong dramatically outnumbered the men. Without available husbands, Tong offered the MacLeod girls no future. They left for the United States, one by one. Mary Anne’s older sister Catherine left first, fleeing the scandal of having become pregnant out of wedlock. She gave birth and left her newborn daughter at home before setting sail for New York in 1921. Within a few years, two more sisters, Christina and Mary Joan, emigrated.

Mary Anne arrived in New York on May 11, 1930 (some reports suggest November 29, 1929), after nine days on the steamship Transylvania. In paperwork, she declared her intention to file for US citizenship.

Although her son Donald would later claim she came to New York on a holiday, papers show that she listed her occupation as “domestic” and had no intention of going back. On one passenger list for all aliens—anyone not a US citizen—she declared that she intended to seek American citizenship, and in answer to “whether alien intends to return to country whence he [sic] came,” she wrote, “no.”

For girls from the fishing hamlet of Tong, the swells under the steamship churning westward would have been familiar. But the first sight of New York City from the harbor was not. Smokestacks poured black coal pollution. The air was hazed with it and with wood smoke from fires. Horses and carriages were still in use, but so were cars and trucks, so the noise of braying and horns and engines added to the cacophony of men shouting in multiple languages.

The magnitude of the metropolis overwhelmed all newcomers, but it also offered a chance to remake oneself. Mainland Scots and those already in the US considered Mary Anne MacLeod a bit of a hick, raised so far from cosmopolitan people and attitudes, undereducated and speaking the Gaelic language. But she had an advantage. Immigrant country girls rendered anonymous in a city so vast and so full of dark alleys might go astray. But the MacLeod girls did not, thanks to a network of recently arrived British, Irish, and Scottish butlers, maids, and footmen all employed in the homes of some of the wealthiest New Yorkers. When Mary Anne arrived, her sister Catherine was married to a butler named George A. Reid. Her sister Mary Joan also worked as a domestic and was married an English footman named Victor Pauley.

Upon arrival at New York, Mary Anne informed immigration officials that she would be staying with the butler’s wife, Mrs. Catherine Reid of Astoria, Long Island. But Mary Anne was soon residing as far from Astoria as it was possible to get — at least in terms of the American class hierarchy. She settled in at 2 East 91st Street in Manhattan, a maid in the service of the widow of the richest Scotsman in the world, Andrew Carnegie.

By 1930, Andrew Carnegie had been dead almost a dozen years, but he was a legend in his native Scotland and the United States. Born in Dunfermline, Scotland, to a politically radical mother and a weaver father in 1835, he emigrated to the United States as a boy in 1848 with his parents. Thanks to a combination of resourcefulness, audacity, and fortuitous timing, he manifested the notion that America could turn any man into a king.

Carnegie’s first job was as a bobbin boy in a Pittsburgh textile mill. He went on to build a vast empire of coal, steel, and real estate. In 1901, he sold his company, Carnegie Steel, for $480 million, the equivalent of about $13 billion today. Among the Gilded Age robber barons who accumulated wealth on a scale comparable to the global oligarchs, Wall Street tycoons, and tech billionaires of today, Carnegie stood out for his community spirit, having vowed to give away as much of his fortune as possible before he died. By the time of his death in 1919, he had donated $350 million—about 90 percent of his fortune. “The parent who leaves his son enormous wealth generally deadens the talents and energies of the son,” he said.

While Mary Anne MacLeod was growing up in Scotland, Andrew Carnegie was already famous and had been handing out millions to libraries, auditoriums, educational institutions, and teachers. Still, he had more of it left over, and in 1901, he built himself an American palace on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, where his widow, Louise Whitfield Carnegie, lived when the teenaged Mary Anne arrived at her doorstep.

Like a character out of Charles Dickens, crofter child Mary Anne landed with the Carnegies, almost magically transported from gazing across the water to the Lews Castle in Stornoway, straight through its windows and into the interior of an even larger castle, this one all-American. Her live-in maid’s position meant she spent her days—and presumably nights (she is listed in the census as a household member)—in an American palace, rubbing shoulders with the closest thing Americans had to royalty, during the depths of the Great Depression.

The Carnegie Mansion was a sixty-four-room gray stone and brick Georgian Revival building, four stories high, covering more than an acre of land on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Among its Trumpian excesses: a hand-carved staircase leading to a massive foyer, a dining room that could accommodate three hundred, multiple fireplaces of Carrara marble, Persian rugs, an art gallery, and a library. Carnegie’s personal favorite after-dinner room was paneled entirely in hand-carved teakwood.

A massive Aeolian pipe organ, its pipes extending three floors, held pride of place on the first floor. During Carnegie’s final years at the house, he hired an organist to play it every morning as his wake-up call. A renowned church organist arrived before the household was up, and, “the music drifted to the second floor bedrooms of the Carnegies where they were gently wakened by their favorite tunes,” wrote one historian. Then the mansion’s twenty servants—of whom Mr. Carnegie wrote, “No man is a true gentleman who does not inspire the affection and devotion of his servants”—went to work organizing the day.

The house was large enough to host massive dinners, and guests from Carnegie’s vast and eclectic group of colleagues, friends, and associates were always in and out, from American writer Mark Twain to international heads of state.

After Carnegie died in 1919, his widow, Louise, remained in the great house, and when Mary Anne arrived to work as a maid, her mistress was in her seventies but still a very vigorous, civically engaged woman, passionate about church, music, dogs, travel, and her grandchildren. The mansion was always filled with music, from organ recitals every Sunday afternoon; to Toscanini, a favorite of the widow, who kept the radio tuned to broadcasts of his recorded concerts; to the Boston Symphony, often on the phonograph. Louise maintained an active social schedule, and Mary Anne watched her bustle in and out, decked in furs and finery, with footmen at her side, headed to operas at the Metropolitan, to dinners with foreign dignitaries, and to lunches with ladies with marquee names like Edison, Colgate, and Rockefeller.

Louise and her retinue also annually voyaged to the Carnegies’ Skibo Castle in Scotland in summer. It’s not certain Mary Anne traveled with them, but ship manifests indicate she did go back to Scotland more than once between 1930 and 1934 — a frequency of travel that would have exceeded the budget of a domestic, unless in service of someone paying for passage.

Ensconced in the Scottish-American community, polishing banisters and silver in a New York castle, one thing remained for Mary Anne MacLeod to do: find a husband.

She met the ambitious, mustachioed Frederick Christ Trump at a dance in Queens. He was six years older, and spoke, like her, with an accent. He owned a burgeoning New York-area building concern. “He was the most eligible bachelor in New York,” Mary Anne would recall, years later, in an interview with the BBC. The two fell in love. Fred Trump was, like Mary Anne, no stranger to hard work. He'd been laboring since his high school years, one winter even substituting his own back for the mules that hauled construction materials to icy job sites. Once out of high school, he went straight into business with his mother. Fred built his first home the year after he got out of high school, for $5,000, and sold it for $7,500. He turned that cash into more houses, and built as fast as he could, selling them before they were completed in order to get the cash to buy materials for the next. “Borrow, build, borrow, buy” became the Trump creed.

On January 1936, Mary Anne married Fred Trump at the Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, followed by a wedding reception for twenty-five guests at the Carlyle, a posh Upper East Side hotel now best known as the venue where Woody Allen liked to play the clarinet. The Stornoway Gazette, Mary Anne's hometown newspaper, published notice of the event. The bride wore a “princess gown of white satin with a long train and a tulle cap and veil,” and her bouquet was of “white orchids and lilies of the valley.” The matron of honor was Mary Anne's elder sister Mary Joan Pauley, and the best man was the groom's brother John Trump (who had by then earned a PhD in physics at MIT).

The couple honeymooned in Atlantic City, but only for two days, as workaholic Fred had deals to get back to in New York City. When the honeymoon was over, Mary Anne MacLeod was no longer living at the Carnegie Mansion, but was listed as a resident of the modest Trump family home at 175/24 Devonshire Road in Jamaica, Queens, the middle-class neighborhood where she was destined to spend the rest of her life. The household was still headed by Elisabeth. Fifteen months after the wedding, on April 5, 1937, Mary Anne gave birth to a daughter, Maryanne, the first of five children, to be followed by Frederick, Elizabeth, Donald, and Robert.

The home life of a Queens builder's wife was hardly high society, but it had its privileges. As Fred prospered, he moved his family into a larger house. By 1940, his wife, the former housemaid, had her own domestic from the British Isles, a naturalized Irish lass named Janie Cassidy. It was a houseful of immigrants. Besides Elisabeth flitting in and out and, eventually, an Irish nanny, there was Mary (she dropped the Anne after marriage), who remained a foreign national until 1942, when the US District Court in Brooklyn made her a naturalized citizen.

Fred's alien heritage was a problem, though. As Hitler rolled over Europe, a second wave of anti-German sentiment infused America. When America went to war against Germany again, Fred Trump declared himself to be Swedish, and he passed himself off as a Swede for the rest of his life, a lie that his son would double down on later, and which would even show up in Fred Trump's Daily News obituary in 1999. “He had thought, ‘Gee whiz, I'm not going to be able to sell these homes if there are all these Jewish people," Trump cousin John Walter, the self-appointed Trump family historian, told the Times later.

And once they started lying, they couldn't turn back. “After the war, he's still Swedish,” Mr. Walter said. “It was just going, going, gone."