The first and last trip of the “unsinkable” Titanic

-

December 1955

Volume7Issue1

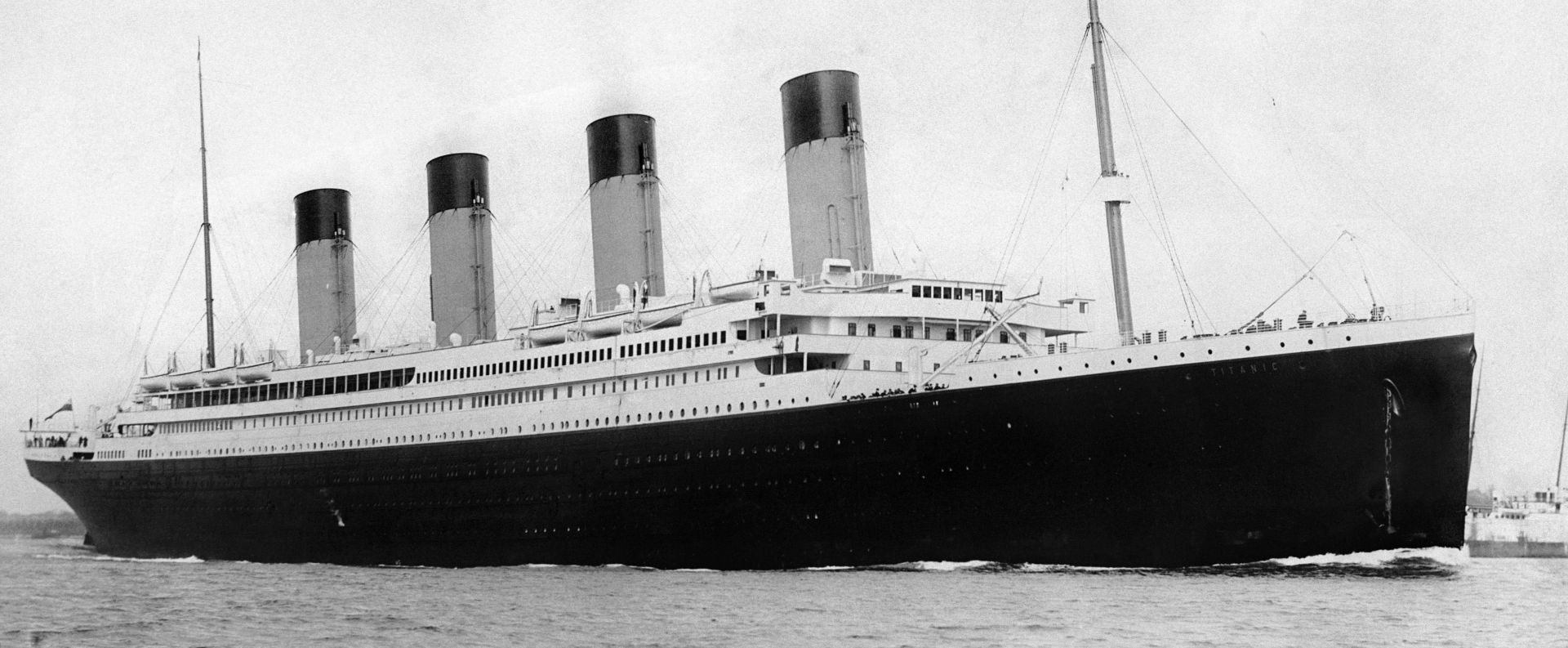

They were missing the maiden voyage to New York of the newest and largest ship in the world. Her weight: 46,328 gross tons, 66,000 tons displacement. Her dimensions: 882.5 feet long, 92.5 feet wide, 60.5 feet from waterline to boat deck, or 175 feet from keel to the top of her four huge funnels. She was, in short, eleven stories high and four city blocks long.

Burgess’ reflections are typical. The Titanic has cast a spell on all who built and sailed her. So much so that, as the years go by, she grows ever more fabulous. Many survivors now insist she was “twice as big as the Olympic.” Actually they were sister ships, with the Titanic just 1,004 tons larger. Others recall golf courses, regulation tennis courts, a herd of dairy cows and other little touches that exceeded even the White Star Line’s penchant for luxury.

No wonder the maiden voyage of this breath-taking ship proved irresistible to so many people—the Countess of Rothes, off to visit her husband’s new fruit farms in California; the George Wideners, who had been shopping for art treasures and Eleanor Widener’s trousseau; sportsman Clarence Moore, who had been buying up foxhounds for the Loudoun Hunt; Major Archibald Butt, President Taft’s military aide, who had just delivered a White House message to the Pope; and so on.

Along with the great came the not even near-great: businessmen; department store buyers; quiet, middle-class English families moving to America; teachers; clergyman; 78 Finnish immigrants bound for new homesteads in the West.

One and all, they trooped aboard throughout the morning of April 10. Meanwhile the windlasses clanked and the winches rattled away, as the last of the Titanic ’s cargo was swung aboard. It was worth only $420,000, but in its way it matched the passenger list—a priceless jeweled copy of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam; 30 cases of golf clubs and tennis rackets for A. G. Spaulding; a cask of china for Tiffany’s; a case of gloves for Marshall Field; a new English automobile for passenger William E. Carter; 76 cases of something called dragon’s blood consigned to Brown Brothers, Harriman.

Now it was almost noon, and Captain Edward J. Smith prepared to cast off. As senior captain, he always took the big White Star ships on their maiden voyages. But this time was something special. He had been 38 years in the company’s service — he was almost 60 — and would retire after this final, crowning trip.

At 12 he ordered the lines freed and rang the engine room telegraph. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the huge Titanic inched away from her dock. As people realized that the gap was growing between the liner and her pier, yells of good-by filled the air. But there was no special ceremony signalizing the maiden voyage, and Second-Class passenger Lawrence Beesley felt mildly cheated.

Slowly the Titanic moved down the harbor. As she passed the American liner New York, there was a series of loud reports. The New York snapped her moorings and drifted out toward the Titanic , irresistibly drawn by the suction of the great liner’s propellers. For a moment, collision seemed certain, but Captain Smith quickly rang off his engines, and tugs dragged the New York back to her berth. The Titanic ’s passengers went down to lunch, excitedly rehashing the narrow escape.

The meal — Potage Hodge Podge, beefsteak and kidney pie, rice pudding — was richly appropriate to the surroundings. The main saloon, a sort of bastard Jacobean in style, was a labyrinth of fluted white columns and heavily carved alcoves. In an adjoining semi-Jacobean room, passengers quickly caught the habit of sipping after-dinner coffee under a big Aubusson tapestry called “Chasse de Guise.”

But on the afternoon of the tenth, they had little time for coffee. Some lined the rail as the Titanic moved down Spithead and passed the Isle of Wight. Others explored the ship — especially the gym, where instructor T. W. McCawley benignly presided over the mechanical horses, camels and bicycles that seemed to fascinate everybody.

Others began to unpack. As First-Class passenger Marguerite Frolicher put her things away, she noticed a life belt tucked between the ceiling and the top of a wardrobe. “What’s that for,” she teased her steward, “if the ship is meant to be so unsinkable?”

At suppertime, the Titanic dropped anchor off Cherbourg and picked up another collection of glamourous people. It took some time to load them all — not surprising, considering that the Arthur Ryersons alone had sixteen trunks for more comfortable traveling. But by nine o’clock everyone was aboard, the tenders bobbed off into the night, and the Titanic turned west towards Queenstown.

It was nearly 1 P.M. , April 11, when the great ship nosed into Queenstown harbor. Again the anchor chains rattled down, again the tenders chugged alongside; but this time there was nothing glamourous about the people who climbed aboard. Patrick Dooley, Kate Hagardon, Jim Kelly, Denis O’Brien, Bridget O’Neil, Pat Shaughnesay — their names gave them away. They were young Irish emigrants, who had bet everything on a steerage ticket to the New World.

With them came a group of visitors burdened with bundles and bulging grips. These were Irish lace merchants, hoping to make a killing during the hour or so the Titanic lay in the harbor. Within minutes the promenade deck looked like an Eastern bazaar, as the merchants and the First-Class passengers haggled back and forth over the wares. John Jacob Astor, perhaps the most magnificent of all the ship’s company, bought a beautiful lace jacket for $800.

While the passengers haggled, a different kind of discussion was going on one deck below, J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, had called Chief Engineer Bell to his suite, B-52. Now they were going over some plans for the trip, Ismay said it was silly to arrive in New York Tuesday night as originally planned; better make it Wednesday morning instead. He also wanted to see how fast the Titanic would run, so he told Bell to open her up Monday or Tuesday.

It was a strange conversation, typical of Ismay’s ambiguous role on board. He liked to picture himself merely a passenger, just going along for the ride. Yet here he was deciding what time to reach New York and how fast to run the ship. Nor did he bother to consult Captain Smith on any of this.

At 1:45 the Chief Engineer, now thoroughly briefed, went back to his engines; the lace merchants packed up their grips; and Fireman J. Coffy, perhaps lured by the green hills of his native Queenstown, deserted ship. Along with the visitors, he marched down the gangway and steamed off home in the tender.

With a long blast from her whistle, the Titanic weighed anchor, swung in a quarter-circle toward the open sea, and moved slowly out of the harbor. All afternoon she steamed westward along the Irish coast, while the gulls wheeled and screamed in her wake. As dusk settled, the coast fell behind and the Titanic was alone in the open sea.

Thursday turned to Friday, and Friday to Saturday, while shipboard life took on its normal pattern. The usual cliques formed. The worldly group—Archie Butt, Clarence Moore, painter Frank Millet—liked to sit around the smoking room and talk politics. Philadelphia Society—the Wideners, the Thayers, the Carters—liked to dine together in the à la carte restaurant; Monsieur Gatti’s continental cuisine made them easily forget they were passing up a free meal in the dining saloon. The gay young set—typical was Lieutenant Bacon Bjornstrom Steffanson, a dashing Swedish officer attached to the Embassy in Washington—went in for lighthearted card games and late evening refreshments in the Café Parisien. The department store buyers—Spencer Silverthorne of Nugents, Ed Calderhead of Gimbels, Tim McCarthy of Jordan, Marsh—weren’t quite as stylish, but that great American institution, the expense account, was already making its presence known.

Life was a good deal duller down in Second Class, where science teacher Lawrence Beesley and the Reverend Ernest Carter liked to discuss the shortcomings of British universities in preparing young men for the church. But Third Class couldn’t have been livelier. The lovely colleens and the strapping Irish boys carried on uproarious hopscotch games in the after well deck while a strolling bagpipe player-children trooping along at his heels—seemed to be everywhere at once.

Meanwhile the crew wrestled with all the minor troubles that beset a new ship. Down in the Turkish bath, Masseuse Maud Slocombe struggled to clean up the mess left behind by the builders. There seemed to be a half-eaten sandwich or empty beer bottle in every nook and corner. “They were Belfast men,” she mischievously explains today. In the engine room, men from the Harland & Wolff shipyard endlessly checked the valves and dials, getting everything in perfect order. In cabin A-36, Thomas Andrews, the builder himself, worked over the ship’s blueprints far into the night—trouble with the restaurant galley hot press, his plan to change part of the writing room into two more staterooms.

On top of the usual troubles a small fire broke out in one of the stokeholds. All Friday and Saturday the stokers shoveled away, trying to get to the source. With one thing and another, nobody paid much attention to the wireless message received Friday night from the French liner La Touraine, warning of ice ahead. Fourth Officer Boxhall dutifully plotted the position on the map in the chart room, but it was over a thousand miles away, and everyone went on with his work.

Sunday, April 14, dawned crisp and clear on a calm, blue sea. Colonel Archibald Gracie, an amateur military historian by way of West Point and an independent income, bounced out of bed for a pre-breakfast warm-up with Fred Wright, the Titanic ’s squash pro. Then a dip in the swimming pool, and up for a huge breakfast.

Others less vigorous lolled in their cabins until time for divine service. Captain Smith conducted and was reasonably brief. He led the passengers in the “Prayer for Those at Sea” and closed with Hymn 403, “Oh God Our Help in Ages Past …”

After services, many of the passengers took their morning walk on A deck (four and one-half times around was a mile), but others preferred to read or write letters. It was getting uncomfortably nippy outside. Mr. and Mrs. Isidor Straus sent a wireless greeting to their son Jesse, who was passing eastbound on the liner Amerika.

Wireless messages were also coming in. At 9 A.M. the Caronia had reported, “Bergs, growlers and field ice in 42° N, from 49° to 51° W.” At 12:45 Captain Smith gave the message to Second Officer Charles Lightoller on the bridge and told him to read it. Now it was after one o’clock, and another warning was coming in. The Baltic reported, “Icebergs and large quantities of field ice … 41° 51′ N, 49° 52′ W.” This meant the ice was about 250 miles ahead.

Captain Smith took the Baltic message and started down for lunch. On the promenade deck he ran into Bruce Ismay, who was taking a pre-lunch constitutional. They exchanged greetings, and the Captain handed the managing director the Baltic ’s ice message. Ismay glanced at it, stuffed it in his pocket, and went on down to eat.

Sunday luncheon was on the heavy side—cockie leekie, Chicken à la Maryland, mashed potatoes, custard pudding. It was a meal that left few passengers in the mood for anything very energetic that afternoon. The French aviator Pierre Maréchal browsed through The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes . Spencer Silverthorne dipped into a new best-seller, The Virginian. Colonel Gracie finished and returned to the ship’s library Mary Johnston’s Old Dominion. He had planted his own book, The Truth about Chickamauga, in the hands of Mr. Isidor Straus, who was dutifully wading through it.

Down in Second Class, Lawrence Beesley struggled with his baggage declaration, and the Reverend Mr. Carter tapped people for a hymn-sing that evening in the Second-Class dining saloon. Third Class was the usual beehive of swarming children, but there were few grownups on deck, because the temperature had fallen to around 45°.

Late in the afternoon the Strauses had an unexpected treat—a wireless from their son on the Amerika, returning their greeting and wishing them love. About the same time the Amerika sent another wireless message, asking the Titanic to relay some information to the Hydrographic Office in Washington: “Passed two icebergs in 41° 27′ N, 50° 8′ W.”

By now the ice was news to hardly anyone on the Titanic. Colonel Gracie heard reports late in the afternoon. And Mrs. Thayer and Mrs. Ryerson got the word straight from Bruce Ismay himself. The managing director, always fond of reminding people who he was, waved at them the Baltic message that Captain Smith had given him.

Dinnertime. As Bugler Fletcher blew first call, Steward Cunningham laid out Thomas Andrews’ evening clothes … the more worldly passengers assembled in the smoking room for cocktails … and Emil Brandeis, the Omaha department store man, held a small party for the buyers in his deluxe suite on B deck. Brandeis’ accommodations cost $4,350 for the six-day trip. They were the most luxurious lodgings afloat, but the pièce de résistance, his own private promenade deck, couldn’t be used this evening. It was by now much too cold.

Up on the bridge Second Officer Lightoller beat his arms to keep warm. He was due to take thirty minutes off for dinner, but before going, he asked young Sixth Officer Moody to compute when they would be “up to the ice.” Moody scribbled away and came up with “about eleven o’clock.” Lightoller, who had by now worked it out in his head, decided the time would be much sooner—probably around 9:30. Then he went below to eat.

The passengers were moving down to the dining saloon too—the ladies resplendent in silk and lace; the gentlemen mostly in tails, although some had switched to that daring innovation, the tuxedo. As Bruce Ismay emerged from the smoking room, Captain Smith asked him to give back the Baltic ice message. Ismay fished it out of his pocket and gave it to the Captain. Then everyone went down to dinner.

In the First-Class dining saloon the buyers had a friendly meal together. The Canadians on board—Major Arthur Peuchen, the Hudson J. Allisons, Markland Molsom—formed another little knot. The Strauses ate quietly alone at a table for two.

It was much gayer in the à la carte restaurant. The Wideners gave a small dinner for Captain Smith, attended by the Carters, the Thayers and Archie Butt. Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon graced a nearby alcove. Bruce Ismay was dining with 62-year-old Dr. O’Loughlin, the ship’s surgeon and a beloved landmark on White Star liners. Other diners were scattered here and there around the walnut-paneled Louis Seize room. The thick vieux rose carpet, the tapestry-covered chairs, the rose-colored shades on the little table lights made the scene an impressive display of post-Edwardian elegance.

Up on the bridge, Second Officer Lightoller returned from his supper break to find the weather colder than ever. In the half-hour he was gone, the temperature had dropped four degrees, from 43° at 7 o’clock to 39° at 7:30. At the same time, another ice message was picked up. The Leyland liner Californian—position 42° 3′ N, 49° 9′ W—reported “three large bergs five miles to southward of us.” This meant the ice was about 100 miles ahead.

By 8:45 the temperature was down to 33°, and Lightoller decided it was time for some special precautions. He sent word to Carpenter J. Hutchinson to watch his fresh water supply—it might freeze up. And he warned the engine room to keep an eye on the steam winches.

In the tropical warmth of the steam-heated Palm Court, few First-Class passengers thought about the cold. They were enjoying after-dinner coffee and a concert by the ship’s band. Everyone agreed that Leader Wallace Hartley’s men were in fine form. When Dr. Will Minahan suggested going to bed around 9:25, Mrs. Minahan begged to hear one more number. So they stayed on, while the band closed with the Tales of Hoffmann.

In Second Class the Reverend Mr. Carter’s hymnsing got under way in the dining saloon. The numbers were selected by popular choice, and it was surprising how many wanted For Those in Peril of the Sea.

In the Third-Class lounge, a lively session of folk dancing was in full swing. The strolling bagpipe player never sounded better. At one point a rat scurried across the room; the music stopped; the girls squealed with excitement; and the young men gave chase. Then the party was on again.

In the bitter cold of the bridge, Captain Smith and Second Officer Lightoller peered into a black, cloudless night. Smith had excused himself from the Wideners’ dinner around nine o’clock—he wanted to go over the ice problem with Lightoller.

The conversation was pretty laconic. Smith remarked it was cold. Lightoller: “Yes, it is very cold, sir. In fact, it is only one degree above freezing.” And he told the Captain about warning the carpenter and the engine room. Smith got back to the weather: “There is not much wind.”

“No, it is a flat calm, as a matter of fact.”

“A flat calm. Yes, quite flat.”

Lightoller remarked it was rather a pity the breeze didn’t keep up while they were going through the ice area. Icebergs were so much easier to see at night, if the wind whipped up waves to dash against them. But they decided that even if the berg “showed a blue side” they would have enough warning. At 9:25 the subject was exhausted and the Captain turned in: “If it becomes at all doubtful, let me know at once. I’ll be just inside.”

Lightoller resumed studying the empty night. At 9:30 he told Sixth Officer Moody to phone the crow’s-nest to keep a sharp lookout for ice, “particularly small ice and growlers.” Moody phoned but didn’t mention growlers. Lightoller, listening, told him to do it again correctly. Moody did. Lightoller nodded, finally satisfied. He wanted no chance of a slip.

Now it was 9:40, and in the wireless shack Operator Jack Phillips jotted down a message from the steamer Mesaba: “Ice report in Lat. 42° N to 41° 25′ N; Long. 49° to 50° 30′ W. Saw much heavy pack ice and great number of large icebergs. Also field ice.” Phillips was busy sending passengers’ messages, so he put the Mesaba ’s report aside until he had a free moment to take it to the bridge. He was no navigator, and it never occurred to him that the Titanic was already in the rectangle indicated by the Mesaba ’s message.

Down below the passengers were going to bed—the perfect solution to a cold, dull Sunday night. The concert over, the Minahans went to their stateroom around 9:45. Colonel Gracie, wanting to be in shape for another pre-breakfast squash match, retired about the same time. Major Peuchen’s Canadian friends went down to bed, and he wandered into the smoking room searching for company.

There he found a few people still up. The remnants of the Widener party sat around one table, winding up the evening with a nightcap. Spencer Silverthorne was buried in a leather armchair, still ploughing through The Virginian. Near him Philadelphian Lucien Smith puzzled over a bridge game with three Frenchmen. A little later Lieutenant Steffanson, Hugh Woolner and some of the young set wandered up from the Café Parisien and began playing bridge too.

In the Second-Class smoking room the card players were quieter and less colorful. Charles Wilhelm, foreman of a London glass factory on a trip to visit his father, played whist with three other men. Steward James Witter hovered nearby, still on duty because Chief Steward Latimer had waived the usual White Star rule of no card playing on Sunday.

On the bridge First Officer William Murdoch arrived at 10 to take over Lightoller’s watch. His first words: “It’s pretty cold.”

“Yes, it’s freezing,” answered Lightoller, and he added that the ship might be up around the ice any time now. The temperature was down to 32°, the water an even colder 31°.

In the crow’s-nest Lookouts Jewell and Symons turned over the watch to Lookouts Fleet and Lee. Symons dutifully passed the word along to keep a sharp lookout for small ice and growlers. The new men nodded and took over. Visibility was good. There was no moon, but the sky blazed with stars. The sea was like glass—not a ripple on its slick surface.

At 11 P.M. Wireless Operator Phillips was still busy sending passengers’ messages to Cape Race for relay to New York—arrival times, requests for hotel reservations, instructions to business associates. Suddenly the steamer Californian broke in: “I say, old man, we’re stopped and surrounded by ice.” She was so close her signal almost blasted his ears off. He shot back sharply: “Shut up, shut up. I’m busy. I’m working Cape Race.” Then he asked Cape Race to repeat the last message, explaining he had been jammed. Little wonder, for the Californian was less than twenty miles away.

Quiet settled over the great ship as the clock moved toward midnight. Major Peuchen left the smoking room around 11:20, and only the die-hards remained. Through the long white corridors that led to the staterooms came only the murmur of people talking behind closed cabin doors, stewards chatting in the deck pantries, occasional “good nights.” Down below, the rhythm of the engines sounded faster and surer than ever. Three new boilers had been lighted that morning in preparation for Monday’s speed trials, and the ship was knifing through the sea at about 22 knots.

Topside, all was alert. On the after-bridge, at the very stern of the ship, Quartermaster Rowe noticed what he and his mates called “whiskers ‘round the light”—tiny slivers of ice in the air that gave off a myriad of colors when caught in the glow of the deck lights.

On the bridge First Officer Murdoch studied the night with equal care. At one point he ordered a fore hatch closed — the glow of light interfered with his vision, and he wanted to take no chances.

In the crow’s-nest Lookouts Fleet and Lee also searched the night. There was little conversation; they were keeping an extra-sharp lookout.

At 11:40 Fleet suddenly spied something directly ahead. It was black, about the size of two tables put together. Quickly he banged the crow’s-nest bell three times and rang the bridge on the phone. Three words were enough to explain the trouble: “Iceberg right ahead.”

Thirty-seven seconds later the new Titanic sideswiped the iceberg, ripping a 300-foot gash in her hull, which opened six watertight compartments and instantly doomed the “unsinkable” ship.