After we published the Papers at the Washington Post, the Supreme Court decision in our favor has underpinned American freedom of the press.

-

Summer 2021

Volume65Issue5

Editor’s Note: Leonard Downie Jr. was a reporter and editor for 44 years at the Washington Post and now teaches journalism at the Cronkite School. During his 17 years as executive editor, the Post won 25 Pulitzer prizes. Mr. Downie has adapted the following essay from his recent book, All About the Story: News, Power, Politics and The Washington Post.

In June 1971 I was working as a city editor at the Washington Post when publication of the Pentagon Papers by the New York Times and our paper created a nationwide furor.

Although I wasn’t directly involved, I had a ringside seat as the publication of the papers shook all branches of the government, and there was a nationwide debate on what constituted “classified” material and how much should be made public.

What became known as the Pentagon Papers was a secret, 7,000-page study of U.S. involvement in Vietnam commissioned by President Lyndon B. Johnson’s secretary of defense, Robert McNamara, and carried out by the Defense Department. It documented a history of missteps and lies by the Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations as they escalated American involvement in what became the costly, lost-cause Vietnam War.

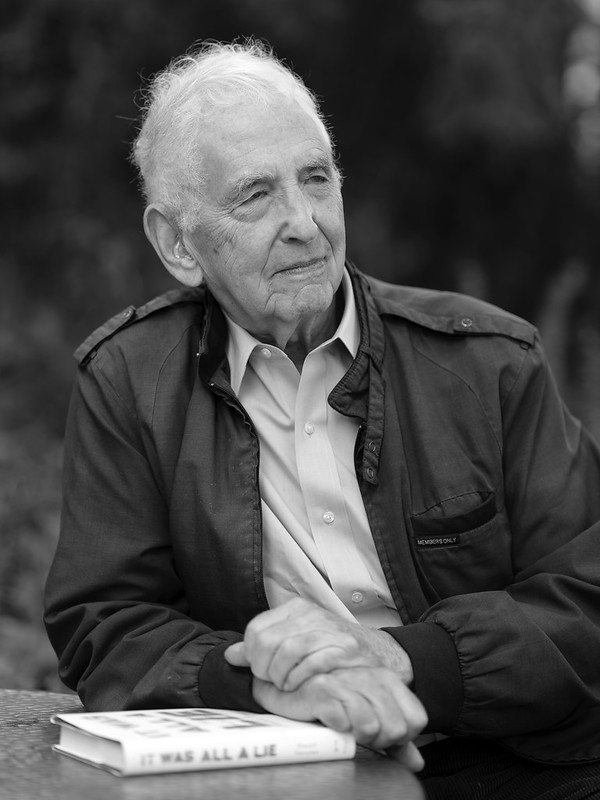

Military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, who had worked on the classified study and evolved into an opponent of the war, spirited a copy out of his office safe at the Rand Corporation in Los Angeles and painstakingly photocopied it page by page over many weeks. After he failed to find interest in it among several Washington officials and politicians, the report made its way to the New York Times.

The first anyone else knew about this was when the Times published its initial story on June 13, 1971. President Richard Nixon, who was already worried about mounting American opposition to the war, asked the Justice Department to seek a court order stopping the Times from publishing top-secret information that, his administration argued, could cause irreparable harm to the United States. An injunction was granted stopping publication, for the first time in American history, after three days of Times stories.

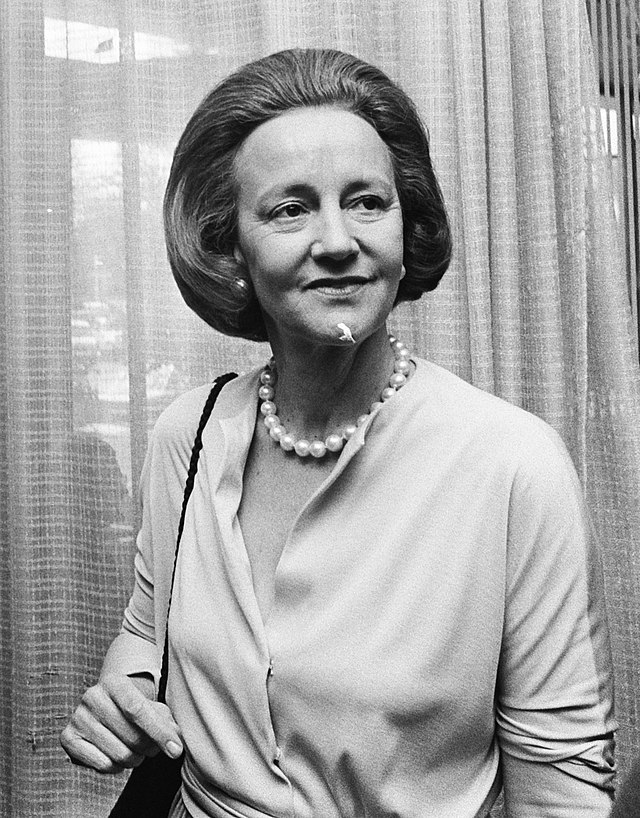

Ellsberg then gave 4,000 pages of the study to Post national editor Ben Bagdikian, who had also once worked at Rand. As depicted in the 2018 film The Post, Executive Editor Ben Bradlee had Bagdikian bring the papers to his Georgetown home, where he assembled a group of Post reporters and editors to produce a story for the next day’s newspaper. The Post’s lawyers and some of its business executives tried to persuade Katharine Graham to stop publication because of the risks of criminal prosecution, loss of the licenses of television stations the Post owned, and damage to the newspaper’s first sale of shares to the public.

But after a tense day of listening to arguments as the journalists worked, Mrs. Graham told Ben in an evening telephone call to his Georgetown home from hers, “Okay. . . . Let’s go. Let’s publish."

Most of us in the newsroom knew little about all of that, even after we saw in the next morning’s newspaper the first of several days of Post stories about the Pentagon Papers.

We never saw what went on at the Bradlee home among Ben, the journalists, the lawyers, Post business executives, and Mrs. Graham. She was still a distant figure to me. There was no sign that her son, Don Graham, a reporter on my city staff, was involved.

Those rushed Post stories about the Pentagon Papers were not the best possible accounts of what was in the report, but they put a marker down. The Post also was forced to stop publishing and to join with the Times in the case that soon went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On June 30, 1971, the Post’s then managing editor, Eugene Patterson, a World War II tank commander who had previously won a Pulitzer Prize crusading for civil rights as the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, stood up on a desk in the middle of the Post newsroom. As we gathered around him, he announced that the Supreme Court had ruled 6-3 that the newspapers could resume publication of stories about the Pentagon Papers.

The federal government was not justified under the First Amendment to engage in prior restraint of publication. And the government never did it again.

The Post and the Times resumed their series of stories about the Pentagon Papers. Even while the Supreme Court appeal was still pending, other newspapers around the country had also started writing about portions of the study circulated by Ellsberg. I could feel in the newsroom a sense that the Post was moving up in class.

The Supreme Court decision would underpin American freedom of the press ever afterward.

Publication of the Pentagon Papers, along with the growing antiwar movement in the country and increasingly skeptical media coverage of the war on the ground in Vietnam, accelerated the erosion of what had been a cozy relationship between the press and the government.

I was still primarily focused on local news.

But the Nixon administration’s efforts to stop publication of the Pentagon Papers — and the decision by Ben Bradlee and Mrs. Graham to defy it — would loom large for me and the newspaper a little more than a year later.

The following year, reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein began their investigation of the break-in at the Watergate Hotel. As Bradlee later wrote, “You had a lot of Cuban or Spanish-speaking guys in masks and rubber gloves, with walkie-talkies, arrested in the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at 2 in the morning. What the hell were they in there for? What were they doing?”

Woodward had a source who told him that there was virtually nothing about the cover-up that Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, had not approved.

Bernstein and Woodward’s April 20 front-page story said that “Dean is prepared to tell a federal grand jury all that he knows about the Watergate bugging and that he will also allege that there was a cover-up by White House officials, including H. R. Haldeman, President Nixon’s principal assistant.”

Even with belated competition from the rest of the news media, the Post owned the story. More sources were becoming more helpful to Woodward and Bernstein by the day, settling scores, and trying to protect themselves, friends, and legal clients, so long as they would not be identified in the published stories.

As I became increasingly involved in editing them, Woodward and Bernstein produced one front-page story after another with new in-formation from their sources. I was becoming experienced and adept at supervising their use of confidential sources, making certain that all important information was corroborated by multiple knowledgeable sources. I knew their stories were more important than ever.

On April 22, Woodward and Bernstein reported that money from the president’s reelection campaign had been set aside to buy the silence of the Watergate burglars. On April 23, they reported that Nixon had been warned that some of his aides were involved in the burglary and cover-up.

On April 27, they reported that acting FBI director L. Patrick Gray had destroyed documents from Howard Hunt’s White House safe after being told by Dean and John Ehrlichman, assistant to the president for domestic policy, that the documents should “never see the light of day”;

Gray resigned that day.

On April 29, Bernstein and Woodward reported that Dean would testify that Haldeman and Ehrlichman were supervising the Watergate cover-up.

And on April 30, they reported that Charles Colson, special counsel to the president, had approved the Watergate bugging.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles on April 27, where Daniel Ellsberg was being tried under the Espionage Act for his release of the Pentagon Papers, the federal judge in that case, Matthew Byrne, announced that the Watergate prosecutors had informed him that Hunt and Liddy had previously supervised a burglary of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in 1971. The burglary was part of illegal surveillance by the White House “Plumbers” unit to combat Nixon’s “enemies” and use wiretaps to find leaks to the media, which Woodward and Bernstein had touched on in earlier stories.

On May 11, Byrne dismissed all the charges against Daniel Ellsberg because of government misconduct.

The next big move was President Nixon’s.

On Wednesday, April 30, he announced on national television that Haldeman and Ehrlichman had resigned and Dean had been fired. Nixon said he accepted responsibility for actions they took in “an effort to conceal the facts from the public, from you, and from me,” without specifying what the facts were. He also replaced the attorney general, Richard G. Kleindienst, with Defense Secretary Elliot Richardson.

Nixon said he gave Richardson the responsibility for “uncovering the whole truth” about the Watergate scandal. The next day, in a grudging answer to a reporter’s question at his press briefing, Ron Ziegler said, “I would apologize to the Post, and I would apologize to Mr. Woodward and Mr. Bernstein.”