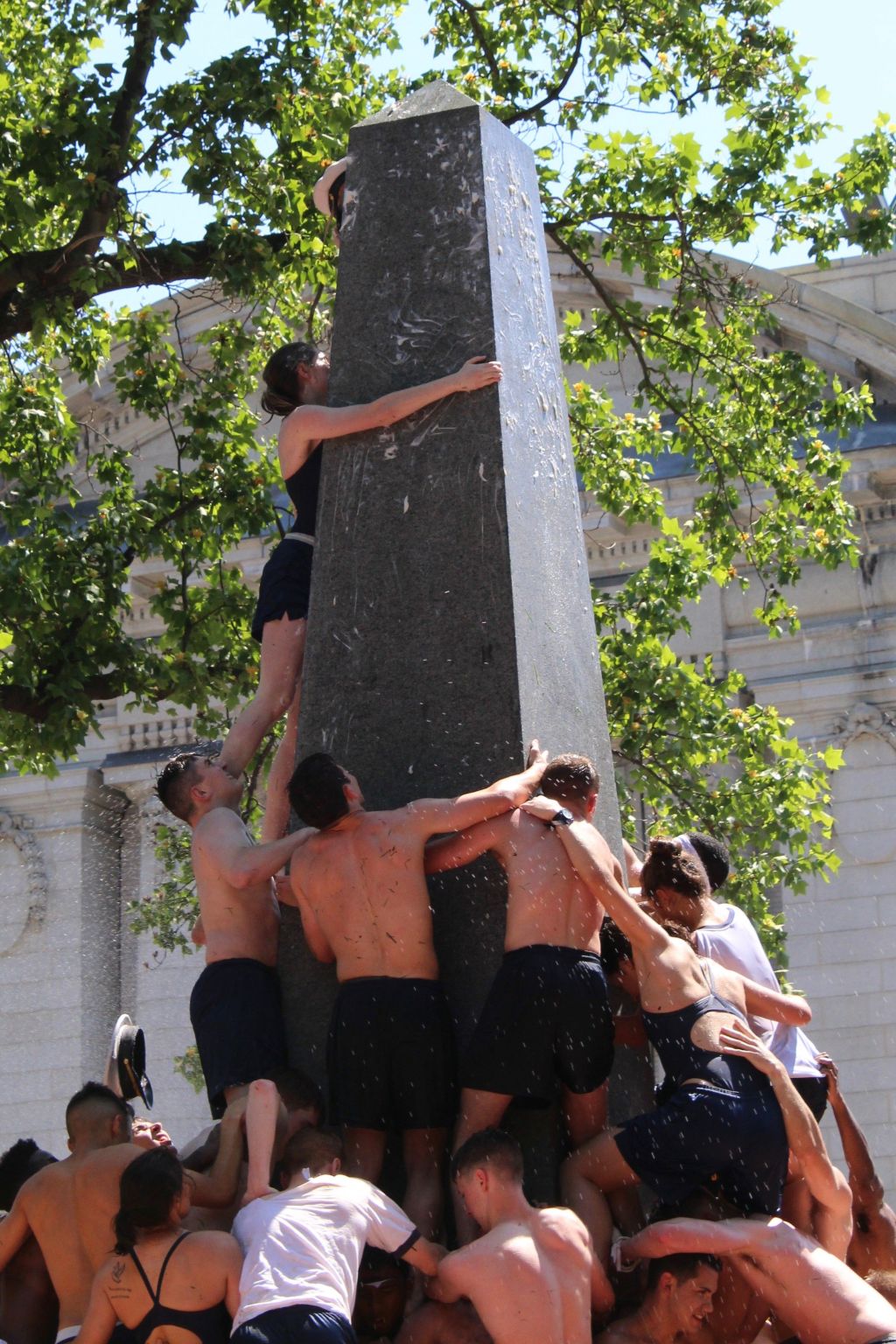

In an annual ritual, Naval Academy plebes must work together to climb a greased obelisk that honors the captain of the SS Central America.

-

June 2021

Volume66Issue4

Editor's Note: Gary Kinder is author of the New York Times bestseller Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea: The History and Discovery of the World’s Richest Shipwreck. He wrote the introduction for a book recently published by the Naval Institute Press, The Herndon Climb: A History of the United States Naval Academy's Greatest Tradition by Rear Adm. James McNeal, SC, USN (Ret.) and Scott Tomasheski, from which this essay was adapted.

It hardly seems a fair fight: twelve hundred buff plebes against one skinny obelisk. And the goal is simple: Lift a plebe’s cap — a “Dixie Cup” — off the pointy top and crown the obelisk with a peaked officer’s “cover.” So why does it take an hour or two, and sometimes four? And an even bigger question: Why at all?

It is May and it is hot. There is little shade, but squeezed into whatever shadows they can find, in a typical year thousands of spectators unpack picnics. Many have watched the Herndon Climb every spring for decades. A few have even participated. Next to graduation, “Herndon” is the most significant experience in Academy life.

To begin the event, a small brass cannon fires a shotgun shell, and while the plebes race toward the monument, let’s look at the bronze plaque at its base, which the plebes have never seen. Until the Herndon Climb, they have not been allowed to approach the grass or walk on the paths that surround the monument. And the plaque is too small to read from even a few feet away. Had they been allowed closer, the plebes would have seen the name “HERNDON” in raised letters on the back side, and they could have read the one sentence cast on the plaque in 1860: “Forgetful of self, in his death he added a new glory to the annals of the sea.”

That is not the full sentence, mind you, but that’s all that was cast on the plaque. It will do for now.

A more immediate concern: Do the plebes running toward the monument know that Cdr. William Lewis Herndon is the only officer in the United States Navy ever to be honored with a monument in time of peace? And do they realize the irony that the Herndon Call they are about to answer differs only in degree from the Herndon Call once answered by five hundred steamship passengers returning from the Gold Rush in 1857?

The sentence abbreviated in the casting originally read: “Forgetful of self; mindful of others, his life was beautiful to the last; and in his death he has added a new glory to the annals of the sea.” The words were part of a eulogy written by the father of modern oceanography, Matthew Fontaine Maury.

When Herndon went down with his ship after battling a hurricane for four days, Maury wanted the world to know that a man had once stood flatfooted on the hurricane deck of a sinking ship carrying the souls of six hundred people and lived an oath he had taken on a calm, sunny day years before: that regardless of danger, he would never abandon his ship.

As Maury knew, many had taken the oath, but few had lived it. Just before he wrote the final sentence above, Maury had written, “A cry arose from the sea, but not from his lips. The waves had closed about him, and the curtain of night was drawn over one of the most sublime moral spectacles that the sea ever saw.”

Maury probably did not know that Capt. Herndon had taken the oath a second time, too, during a genteel dinner at the captain’s table as the SS Central America steamed toward the edge of the storm. He was dining with several guests when convivial conversation turned to a topic popular at the time: shipwrecks.

Three years earlier, the crew of a sinking steamer had abandoned their ship to rescue themselves, leaving the passengers to perish. One of the dinner guests later recalled Herndon’s charming segue from sinking ships to more pleasant topics: “Well, I’ll never survive my ship,” he told his guests. “If she goes down, I go under her keel.”

The story of Herndon and the SS Central America is one of the great epics of American maritime history. It begins with the founding of a new American territory, California, and a discovery of the one thing there besides land that everyone wanted: gold. Within a few short decades, the California Gold Rush fundamentally transformed the new territory, drawing tens of thousands of hopeful pioneers to the west coast and turning small coastal outposts like San Francisco into major seaports. And to facilitate that explosive growth, new steam ship routes were established, including one across Panama that represented the fastest and easiest way to get from one end of the continent to the other.

From 1849 to 1869, 410,000 passengers traveled west over Panama and another 232,000 journeyed back east. Of those who crossed the Great Plains on foot, the second easiest route, most returned by sea. The ships carried passengers of means, persons helping to shape the American West, and for the first twenty years they carried nearly every ounce of California's precious export.

Officially cataloged, duly recorded and delivered, $711 million in gold passed over the Panama route, and $46 million went via another route later established across Nicaragua. Every two weeks, a steamer departed San Francisco, with cargo and passengers bound for the East, and carrying a commercial shipment of gold weighing close to three tons.

One of those ships was the SS Sonora, which departed San Francisco Bay in July 1857 carrying five hundred passengers, thirty-eight thousand letters, and a consigned shipment of gold totaling $1,595,497. In Panama, the ship’s passengers would cross the isthmus and board the SS Central America, a 280-foot Atlantic steamer that would make the final trip of nine days across the Caribbean and up the East Coast to New York, with an overnight call in Havana.

One of a new generation of sidewheel steamers, the Central America departed New York Harbor on the twentieth of each month, bound for Panama, where she traded New York passengers bound for San Francisco for California passengers returning east. Since her christening in 1853, she had carried one-third of all consigned gold to pass over the Panama route. And in quantities rivaling her official gold shipments, unregistered shipments of gold dust and gold nuggets from the Sierra Nevada, and gold coins struck at the new San Francisco Mint and gold bars, some the size of building bricks, had traveled aboard her in the trunks and pockets, the carpetbags and money belts of her passengers.

For many of her passengers, the final five days to New York would be the last leg of a long journey that began when news of the rich gold strike in California had first trickled east. On Tuesday, September 8, 1857, at 9:25 A.M., the Central America crossed the Tropic of Cancer, and with the green hills of Cuba shrinking behind the whitened wake, the captain took her into the Gulf Stream, which he would follow most of the way to New York.

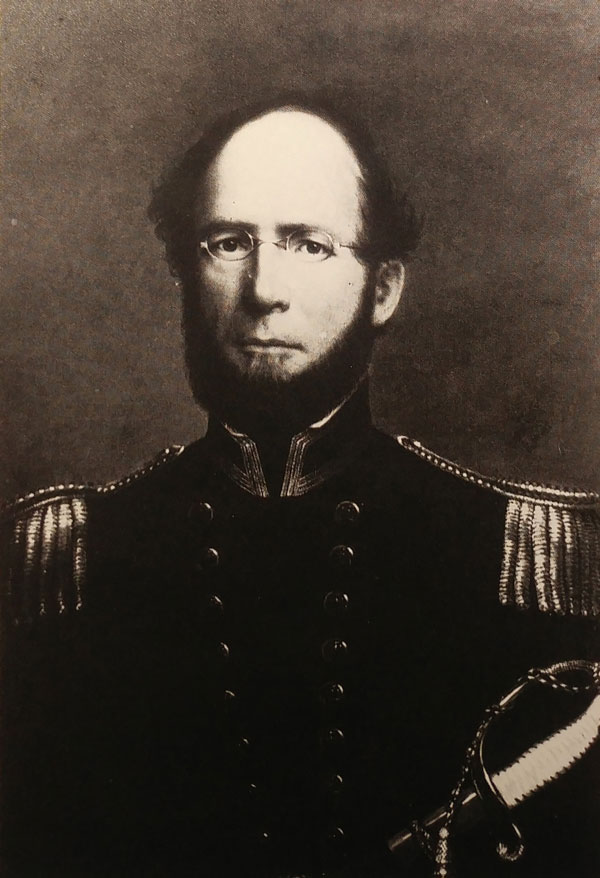

At the head of the captain’s table sat Herndon. Married and the father of one daughter, he was slight, and at forty-three balding; a red beard ran the fringe of his jaw from temple to temple. Though he looked like a professor or a banker more than a sea captain, Herndon had been twenty-nine years at sea, in the Mexican War and the Second Seminole War, in the Atlantic and the Pacific, the Mediterranean and the Caribbean Sea. He knew sailing ships and steamers and had handled both in all weather. He was also an explorer, internationally known and greatly admired, who had seen things no other American and few white men had ever seen.

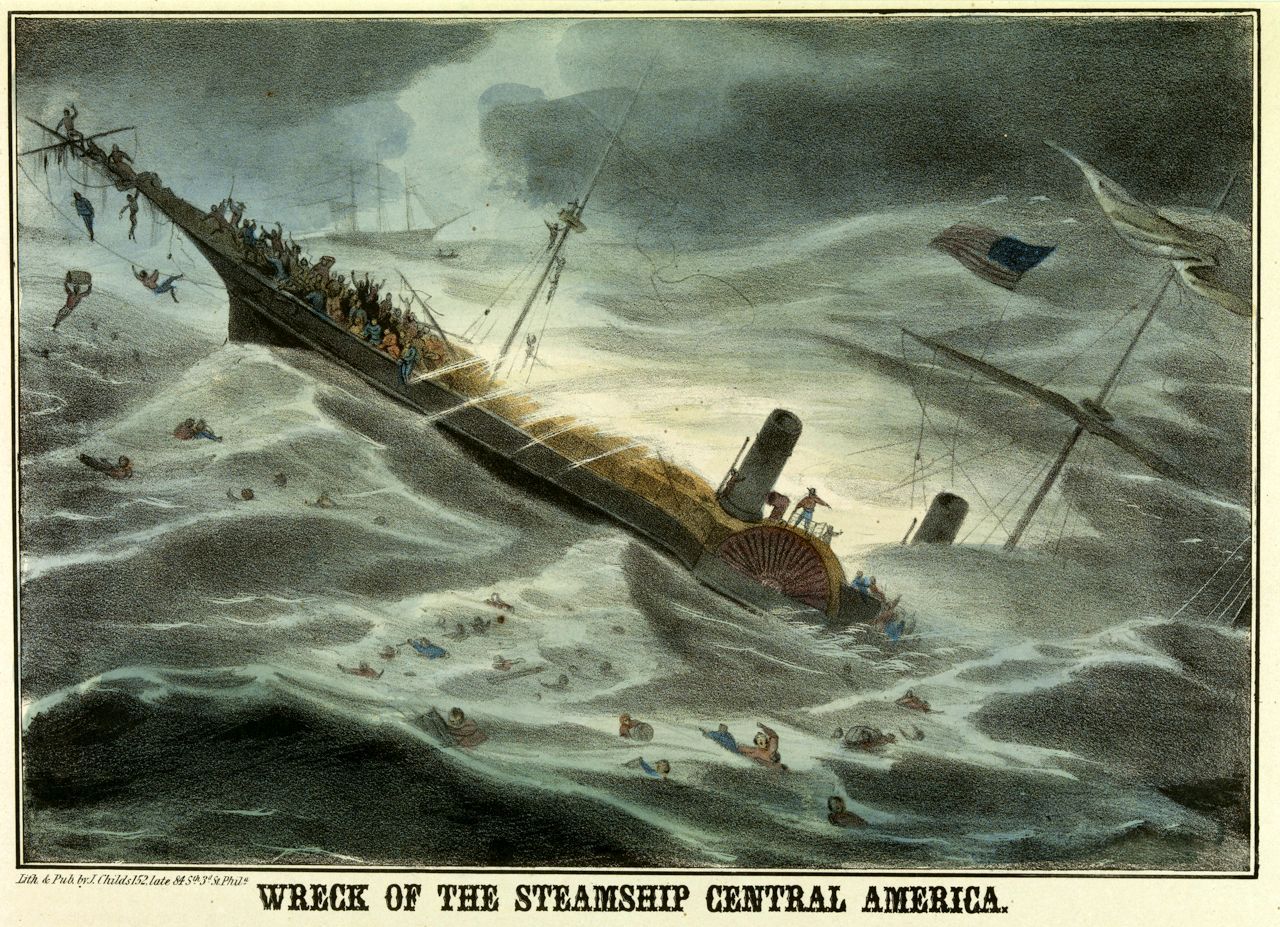

By Thursday morning the Central America had veered two hundred miles east of St. Augustine. High seas broke over the bow, sprayed across the decks, and splashed against the staterooms. Sometimes the steamer heeled so far that the housing over her paddle wheels rolled under water. Soon a full-blown hurricane swept in, which grew worse and worse over the ensuing hours. Even more dire, the ship sprung leaks, eventually disabling its steam engines and leaving it stranded and adrift as the wind and waves mounted. The Central America was sinking.

In the early 1900s, the ritual of climbing “Herndon” began with plebes snake-dancing around the monument, celebrating having survived a grueling first year at the Academy. The dance would have been the first time they had been allowed on the monument’s surrounding lawn and the adjacent path, “Lover’s Lane.” Eventually, the ritual dance would end with one plebe climbing the obelisk, which officially marked the end of their “plebe” status and provoked hundreds of voices chanting “Plebes no more!”

Later, an officer’s “cover” would be placed at the top for the climber to retrieve, a symbolic touch; and later still, another symbolic touch: a plebe’s cap, or “Dixie Cup,” would be placed at the top for the climber to replace with the officer’s cover. As McNeal and Tomasheski write, “The exchange of caps at the apex further cemented the profound meaning of the Climb as an important step in the life of every midshipman.” With that, the Herndon Climb became “a ritual in Academy culture second only to graduation.” And that was the last change to the Herndon Climb. Except for one that greatly evened the odds.

Right now, the first plebes have reached the monument and have begun forming a human scaffold around the base, linked arm-in-arm, like a rugby scrum, on top of a rugby scrum, on top of a rugby scrum, with the monument in the middle. And on top of that last scrum a few “monkeys,” the lightest, scrappiest, most agile of the soon-to-be-plebes-no-more, will inch their way toward the top, each balancing a cover to replace the Dixie Cup.

To them all, “Herndon” is the name of a long-forgotten someone who did something once upon a time, but few know what or when. For them, “Herndon” has become an event: a rite of passage, a line to cross from being an absurdity—less than nothing-to being persons; from being plebes to being plebes no more. To be one, but become the other, they must do Herndon.

At a height of twenty-one feet, the monument is hardly imposing. The first officially timed Herndon in 1962 was over in twelve minutes. But over the years, the great leveler “grease” became a tradition, and the time slowed from minutes to hours as the plebes tried to climb twenty-one feet of granite slicked with fifty pounds of lard. And the plebes’ only resource, as the authors explain, is “the combined strength of their own bodies” and the ingenuity and teamwork of classmates. And that’s where the Herndon Call of today ironically begins to overlay the Herndon Call of 1857.

As seawater pouring into the hold silenced the Central America’s steam engines on the third day, Captain Herndon appeared in the dining salon, where the passengers huddled, and called for volunteers to keep the three-hundred-foot steamer afloat like they would a rowboat: by bailing. With passengers hardened by years in the gold fields and packing weapons, mutiny was common, but five hundred men obeyed Herndon, because he did nothing to save himself.

From first class to steerage, from miners to carpenters to vaudevillians, they formed three lines from the hold almost four stories up to the deck and passed buckets, basins, and pitchers filled with water throughout the night and into the next day, thirty-six hours, some passing out from exhaustion. Herndon seemed at once in all parts of the ship, cheering the men beyond what they thought they could do. “Work on, m’boys,” he would say. “We have hope yet.”

Though few passengers had family with them, their selfless teamwork in answering Herndon’s call bought just enough hours to transfer all sixty women and children and a hundred men to another ship that appeared miraculously out of the storm. To this day, that rescue two hundred miles at sea is one of the finest hours in American history.

Each year in May, several hundred plebes answer the other Herndon Call. No one’s life is at stake, but they can accomplish the Climb only by building a broad human scaffold nearly three stories high with nothing to hold on to but each other, and with their granite nemesis and themselves slippery with lard. One graduate who placed the cover in his plebe year told the authors, “You get a little disappointed when you all crumble down the greasy thing and start going again, but the feeling you have when it’s over is like no other.”

A few superintendents have tried to tame Herndon, to make it less difficult, less dangerous, but for what are our finest military women and men preparing if not the difficult and the dangerous? The superintendent in 2010 outlawed using grease, but the “scaler” scrambled to the top in two minutes and five seconds. Not much of a challenge and little need for teamwork. The following year, a new superintendent, more concerned about instilling “spirit and camaraderie” within the plebe class and between that class and the classes before who had done Herndon, ordered the grease back on the granite. Exhausted but gratified, the plebes that year took two hours and forty-one minutes to place the cover on top.

One commander acknowledged there will always be strains and sprains and cuts and bruises suffered in the Herndon Climb. “But we also don’t want to develop a fighting force that we’re unable to send out into the desert, send to the front lines, because we pampered them.... We’ve got to have people that are used to doing this kind of thing. [The Climb] is that same kind of teamwork building, even though it isn’t combat. It’s about the mental fortitude, accepting challenges and getting out of your comfort zone.”

“Herndon” has grown beyond a monument, even beyond an event: It has become a metaphor for life in the military — selflessness, perseverance, and teamwork — the ultimate test of a mass of women and men figuring out how to work together toward a common goal, no one caring who gets the glory.

As Adm. McNeal and Scott Tomasheski write in their book The Herndon Climb, “The Climb is generally viewed as an exercise in cooperation and team building as much as it is a grueling physical challenge for those who throw themselves into the crowd, putting their bodies on the line, and pushing the limits of their strength and endurance.”

Watch a Herndon Climb on YouTube. It will make you groan and gasp at the near misses and cheer at the small and ultimate triumphs. As you watch, know that much of Capt. Herndon’s charm was his self-mocking humor: He loved to regale an audience with punch lines that underscored that the joke was on him. Were he to witness the plebes doing “Herndon” today, I am certain he would laugh the longest and cheer the loudest.

I hope that none of these plebes will be tested as Herndon was, and that if they are, they will remember the example he set and the legacy he left behind.

I also hope people outside the Naval Academy learn more about the Herndon tradition. It deserves such a following. Because Admiral McNeal went through the Herndon climb at the end of his own plebe year — a body in the bottom scrum — his experience informs the firsthand accounts in their book that he and Tomasheski teased out of others who have done “Herndon.”

Even if you didn’t attend the Academy and don’t know anyone who did, the personal stories of victory and sacrifice on the Climb and later on duty inspire. When so many of our leaders show little regard for integrity, selflessness, and honor, we need to be reminded of real heroes, like these young women and men and like William Lewis Herndon.