Why the UN was in trouble from the start

-

August/September 2003

Volume54Issue4

In the months before the war to overthrow Saddam Hussein, two words kept cropping up in the vocabulary of its opponents: sovereignty and legitimacy. The war, they said, would threaten the sovereignty of an autonomous state (the Ba'ath party’s Iraq), and it would lack the legitimacy conferred by the backing of the United Nations. As one journalist put it, an invasion would be “the first test of the new doctrine … that the United States has the right to invade sovereign countries and overthrow their governments. … At stake is not just the prospect of a devastating war but the very legitimacy of an international system built over the past century that—despite its failings—has created at least some semblance of global order and stability.”

Such concerns were very widely felt. Robert Kuttner, the co-editor of The American Prospect, wondered if “other sovereign nations [are] prepared to accept the status of cattle.” Jacques Chirac, president of France, warned against “throwing off the legitimacy of the United Nations.” Even Colin Powell conceded that the UN would have to become involved in rebuilding Iraq for the sake of “international legitimacy.”

There is a problem with these concerns, a contradiction at the heart of the United Nations. It’s a paradox with roots that stretch back to Woodrow Wilson’s 1918 plan for a world without war and to Eleanor Roosevelt’s valiant struggle after World War II to place the rights of individuals above the rights of states. The problem is simply stated: Sovereignty and legitimacy are crucial to modern liberal internationalism, and so is the defense of human rights. Yet they can be completely at cross-purposes. Suppose a sovereign state willfully violates the human rights of its citizens and the legitimate international community fails to intervene? Which is more important, international law and the equality of states or the rights of individuals?

The principle of sovereign equality can be traced back across more than three centuries to 1648 and the Treaty of Westphalia. Besides bringing an end to the Thirty Years’ War, Westphalia formed the cornerstone of what became the modern system of states. In giving independence to the nations that had made up the Holy Roman Empire, Westphalia went a long way toward establishing a general belief that the internal affairs of a country—the religion it favors, the freedoms it allows—were the legitimate concern only of its own government. According to this modern notion of sovereignty, a prince was constrained in what he could do outside his nation but essentially enjoyed free rein within it.

This ideal of state sovereignty endured a grave threat during World War I, when the competing interests of Europe’s great powers erupted in a clash that introduced new levels of violence and destruction. In response to the carnage, President Woodrow Wilson sought to create a world order that would ensure a durable peace. In 1918 he surprised a joint session of Congress with a number of bold proposals known as the Fourteen Points. The most important was a call for a “general association of nations” that would safeguard “the independence and territorial integrity [of] great and small states alike.” The result was the League of Nations, the forerunner of today’s United Nations. Senate resistance prevented America from joining the League, but Wilson’s faith in international cooperation struck a chord among many at the time, and it continues to resonate today. As the historian Alan Brinkley explains, it was a vision “strongly rooted in the ideas of progressivism, that the world was as capable of just and efficient government as were individual nations—that once the international community accepted certain basic principles of conduct, and once it constructed modern institutions to implement them, the human race could live in peace.”

Also central to Wilson’s public philosophy was an appreciation of democracy and human rights. “No peace can last, or ought to last,” he declared, “which does not recognize the principle that governments derive all their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The following year the President called for the “destruction” of “arbitrary power anywhere in the world.” He apparently didn’t notice any contradiction between the independence “of great and small states alike” and opposition to “arbitrary power anywhere.”

Thirty years later the world had occasion to revisit Wilson’s principles. If World War I challenged international leaders to uphold the integrity of sovereign states, World War II introduced a new imperative, safeguarding the rights of human beings. The German and Japanese race-cleansing campaigns were not entirely unprecedented (the Armenian genocide of World War I stands out as an earlier example), but they were certainly unprecedented in their awful magnitude.

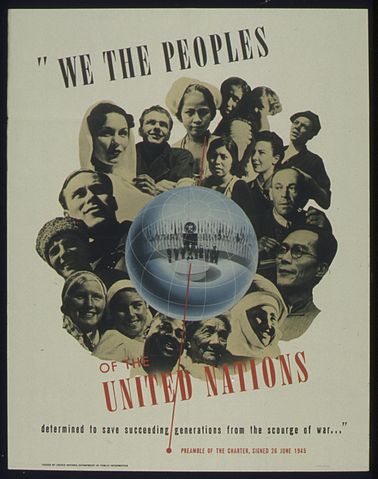

In the spring of 1945 representatives of 50 nations gathered in San Francisco to finalize a charter for the United Nations. Like the League of Nations, the UN was created as a guard against regional conflict. Rooted in Wilson’s conviction that small wars were bound to ignite global ones, the UN created a more sophisticated set of mechanisms to enforce the integrity of borders and state sovereignly. But the new organization went a step farther. It realized it must also protect individuals from their own leaders.

In 1947 a remarkable United Nations committee, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, convened in Paris to draft a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the first document of its kind in history. The task was not a simple one. Delegates from the four corners of the earth would have to agree on basic principles limiting how states could behave not only toward one another but also within their borders. Not surprisingly, the first sessions were contentious. The committee included Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, atheists, and agnostics; communists, socialists, liberals, and fascists; Western and Eastern nations; colonial powers and recently decolonized nations—all there to concur on a guiding set of ideals that would protect human dignity without compromising cultural differences.

Eleanor Roosevelt proved equal to the task. Armed with a kind and unassuming demeanor but also with a razor-sharp intellect and diplomatic skills that surprised even the greatest skeptics, she devoted months of study to the intricacies of international law and single-mindedly forged a compromise among the committee’s competing factions. For instance, she helped strike a critical balance between AngloAmerican notions of liberty, which exalted the individual, and Continental ones, which stressed a state’s obligation to ensure the economic and social well-being of its citizens.

Her efforts found reinforcement in the work of an extraordinary panel of philosophers gathered by the UN’s Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Under the capable direction of the Cambridge University historian E. H. Carr, the Committee on the Theoretical Bases of Human Rights asked a group that included Aldous Huxley, Mohandas Gandhi, the Jesuit philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the Confucian philosopher Chung-shu Lo, and the Bengali Muslim poet Humayin Kabir if it was possible to identify values that cut across all national, ethnic, religious, and regional boundaries. Much to the surprise of many, and to the delight of Eleanor Roosevelt, their answer was an emphatic yes.

“Varied in cultures and built upon different institutions, the members of the United Nations have, nevertheless, certain great principles in common,” the committee reported. It went on to identify specific values that were shared across cultures and continents. Mary Ann Glendon, a scholar of human-rights law, sums them up as “the right to live; the right to protection of health; the right to work; the right to social assistance in cases of need; the right to property; the right to education; the right to information; the right to freedom of thought and inquiry; the right to self-expression; the right to fair procedures; the right to political participation; the right to freedom of speech, assembly, association, worship, and the press; the right to citizenship; the right to rebel against an unjust regime; and the right to share in progress.”

These broad ideals ultimately guided Eleanor Roosevelt’s committee in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a nonbinding statement of principle that the participants in the conference ratified in 1948. One delegate wrote that the formal UN debate, held at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, was marked by a “great solemnity, full of emotion.…I perceived that I was participating in a truly significant historic event in which a consensus had been reached as to the supreme value of the human person, a value that did not originate in the decision of a worldly power, but rather in the fact of existing.”

After the 34 delegates had exhausted every possible angle of debate, the General Assembly voted to approve all 30 articles of the declaration, 23 of them unanimously. When the complete document came up for a final ballot, no nation voted against it. Only 8 abstained: Byelorussia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine, Yugoslavia, and their patron, the U.S.S.R.; Saudi Arabia; and South Africa.

However, its passage was largely symbolic. The problem was, and is, that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an assortment of non-binding principles that are fundamentally at odds with the binding rules governing the United Nations. Then, as now, in the perpetual tug of war between state sovereignty and human rights, state sovereignty almost always wins. Article 2 of the UN Charter is very clear on this point: The United Nations “is based on the sovereign equality of all of its members.” Which means that a brutal dictator has as much right to be there as the delegate from a democratically elected government that respects the Universal Declaration. Moreover, it has to be that way. Sovereign states are what the UN consists of.

Thus the fundamental contradiction of modern internationalism: It seeks to balance the rights of the state with those of the individual, but it often can’t. Eleanor Roosevelt understood this all too well, and she viewed the Universal Declaration as a necessary counterbalance to the UN’s interest in the preservation of sovereignty and stability. A 1947 political cartoon showed the former First Lady as a schoolteacher, telling her students—the other members of the declaration’s drafting committee—“Now, children, all together: ‘The rights of the individual are above the rights of the state.’”

But isn’t so. Increasingly in recent years, internationalists have stressed the latter at the expense of the former—inevitably to the detriment of the principle of human rights. The UN’s expression of concern can rarely be more than rhetoric. Today Libya chairs the UN’s Commission on Human Rights. The UN recognizes Libya and its government as sovereign and legitimate, and so investigations of matters from cases of torture and mass murder to extralegal confinement of dissidents are headed by Ambassador Najat Al-Hajjaji, a woman picked by CoI. Muammar al-Qaddafi.

As a result, nations and coalitions constantly have to work around the UN. It happened when the United States and Great Britain established a no-fly zone over northern Iraq in 1991 to stop Saddam Hussein’s attacks on the Kurdish population there. It happened when NATO forced Slobodan Milosevic to abandon his policy of “ethnic cleansing” of Albanians and Kosovars in 1999. It happened when Israel bombed Iraq’s Osiraq nuclear reactor in 1981, preventing Saddam Hussein from acquiring the ultimate weapon of mass destruction. And it happened when Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978 to overthrow Pol Pot, a man responsible for the death of as many as two million of his own citizens. Surely, if the principles of sovereignty and legitimacy hadn’t been disregarded, the terrors of this world would be more terrible still.

Where does all this leave the United States? In something of a bind. In many ways the legacy of Westphalia stands in contrast with that of the Founders, who, in adopting the Declaration of Independence, affirmed that governments are created to secure the rights of humankind, “deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Therefore, if a government suppresses the rights of its citizens, it loses its legitimacy. “A Prince,” states the Declaration of Independence, “whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

From this perspective, regardless of what the UN Charter stipulates, authoritarian regimes that treat their people like chattel are not legitimate governments. And while their forceful removal may not always be prudent or practical, it is praiseworthy if it brings in a morally legitimate authority. This is an extreme position, to be sure, and it has always had its opponents. In recent decades, in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, many have come to the conclusion that the United States and its government could no longer be trusted to do the right thing.

Can America be trusted today to establish morally legitimate governments in countries it subdues? Most human-rights advocates remain skeptical, pointing to the twentieth century, when, for reasons ranging from cultural chauvinism and economic self-interest to Cold War panic, the United States found itself making very unsavory friends. Moreover, if a government derives its just powers from the consent of the governed, then it follows logically that no one can justly overthrow that government except by the consent of the governed. Getting the consent of an oppressed population may be impossible, of course, but without it any coup always has a taint of the arbitrary.

There are grounds for optimism though. Since Vietnam, American Presidents have been more alert to the cause of human rights. After the United States invaded Grenada in 1983, the communist junta of Hudson Austin and Bernard Gourd was replaced by a government that allowed a free press and opposition parties to flourish. The same held true in Panama following the U.S. invasion in 1989. Today Panama has an independent judiciary, an opposition press, and several vigorous political parties; executive power has changed hands two times, peacefully and constitutionally.

In Haiti, where the U.S. threat of invasion in 1994 forced out the military dictatorship of Gen. Raoul Cedras, the picture is murkier. Political violence is common and government corruption is rampant, but there are opposition parties and an opposition press. Most impressive, various members of the Haitian judiciary have been willing to stand up to President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, ruling against his government on important issues. Free institutions, fragile as they may be, are now stronger as a direct result of American intervention. In Afghanistan there are already signs of hope: women no longer compelled to wear veils, families free to attend movies, girls able to go to school, and democratic elections scheduled for next year.

Of course there are those who see America not as a liberator but as a hegemon. An article titled “The Case Against Intervention in Kosovo,” which appeared in The Nation in 1999, argued implicitly that respect for state sovereignty should outstrip concerns about human rights. Comparing the Kosovars with Southern secessionists during the American Civil War, the authors asserted that “the province of Kosovo (the cradle of Serbia’s cultural and national identity) is an integral part of Serbia’s sovereign territory. … This conflict is, of course, a civil war, the root of which is the province’s ethnic Albanians’ armed struggle to break free of Serbia and establish an independent state. Thus, as in numerous ethnic conflicts in the Balkans and elsewhere, the opposing sides’ objectives cannot be reconciled.” Perhaps not, but absent from this description of the Balkan wars was any mention of mass graves, rape camps, and ethnic cleansing.

America’s behavior on the international stage will doubtless continue to be shaped, as it has in the past, by a combination of principle and pragmatism—serious consideration of what we should do, tempered by careful deliberation on what we can do. The United Nations will doubtless continue to seem more useful when it advances the cause of human rights than when it doesn’t. As Grenada, Panama, and Haiti suggest, it is possible to flout international law without suffering any serious fallout. In each of those cases, America’s defying the UN led not to chaos but greater stability. It didn’t cause a crisis at the United Nations, and it did further the cause of human rights.

When America defies international law, does it not encourage every two-bit dictator to do the same thing? That fear prompted Kofi Annan to oppose NATO’s attack on Serbia in 1999. He deplored ethnic cleansing but advised against foreign intervention because the Security Council hadn’t authorized it. If the members of NATO got militarily involved, he asked, “how could they tell other regions or other governments not to do the same thing without Council approval?” However, authoritarian regimes are far more often constrained by power than by considerations of right and wrong. During the Cold War it was not Western restraint that prevented the Soviets from invading Western Europe but the fear of nuclear annihilation. In the 1930s it was the passivity of Britain and France, not their aggressiveness, that enabled Germany to wage its campaign of aggression.

In the aftermath of NATO’s action against Serbia, it became more widely accepted that humanitarian intervention—that is, the violation of a country’s sovereignty in order to secure humanitarian objectives—may sometimes be a worthy choice. Annan himself, after initially opposing the NATO action, said, “There is an emerging international law that countries cannot hide behind sovereignty and abuse people without expecting the rest of the world to do something about it.”

Some, Annan among them, hope a stronger UN will play this role. Yet a stronger United Nations is still a United Nations. It must continue to be populated with, if not dominated by, governments that place little stock in human rights. But as Annan’s changing views suggest, sovereignty is not sacred. And when policy changes, international law tends to follow. The UN quickly recognized the new U.S.-backed governments in Grenada and Panama, and, since NATO’s intervention in Kosovo, what has been called an “evolving international law” has begun to accord less importance to sovereignty and more to the rights of the individual.

In Henry V, Shakespeare’s Harry tells his soon-to-be-queen, “Nice customs curtsy to great kings. Dear Kate, you and I cannot be confined within the weak list of a country’s fashion; we are the makers of manners, Kate.…” America may need to exhibit less hubris than the victor of Agincourt, but its ability to reshape convention is no less great. And because with power comes responsibility, America may feel compelled to champion the twin causes of human rights and legitimate government ever more forcefully. History has shown that the United Nations often cannot do the job.