Funding the Civil War with an Income Tax

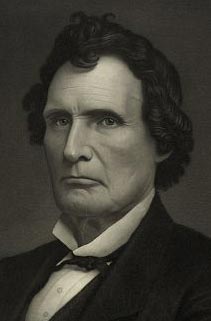

Radical Republican and Ways and Means Committee chairman Rep. Thaddeus Stevens advocated a property tax to pay for the Civil War.

The Confederates’ decisive defeat of Union forces at the Battle of Bull Run/Manassas so shocked the U.S. government that it instituted an income tax for the first time in American history. The defeat came at the hands of an outnumbered, underfunded, and inferiorly supplied Confederate army. It left Gen. George McClellan braying for more men, imagining a massive Napoleonic army capable of crushing the rebels in one decisive campaign. He wanted at least 273,000 soldiers and sailors at an average cost of $1,000 each. The older, and more seasoned, Gen. Winfield Scott, was pushing a strategic plan that would cost scarcely less: it required a greatly strengthened Navy and strong armies on both sides of the Mississippi River.

As the U.S. government scrambled to raise its armies, it faced a mounting debt of more than $150 million, an astronomical sum that did not even account for funding the war into the following year. Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase estimated the U.S. government would need to borrow $240 million to supplement its current annual income of $80 million, which was derived from indirect taxes, tariffs, and public land sales. (Once 1862 began, his estimate would leap to $530 million.) Such enormous debt, owed mainly to American banks, could cripple the United States, as it later would prove to cripple the Confederate States. The usual way of generating income through tariffs would prove insufficient, but might also turn the Western states, on which the tariffs fell hardest, against the government.

In a difficult position, the President and the Republican Party considered the unthinkable, a tax on income, which was (and still is) anathema to the Republican ideal of unfettered private enterprise. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, the influential chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, addressed the House on July 24, three days after Bull Run:

I believe that many thousand valuable lives will be lost and that millions of money will be expended. The only question is whether this government is prepared to meet all these perils and to overcome them. If they are they must submit to taxes which are burdensome, which the people I know at any other time would not submit to for a moment, but which I believe they will now submit to.

The idea of a property tax was unpalatable to most congressmen, including Stevens’s fellow Republican Rep. Schuyler Colfax of Indiana, who raised several valid points. What, after all, was the definition of taxable property? Did it include merely real estate, as it had in the past, or extend to the stocks and bonds and other investments generally held by the wealthiest citizens in the country?

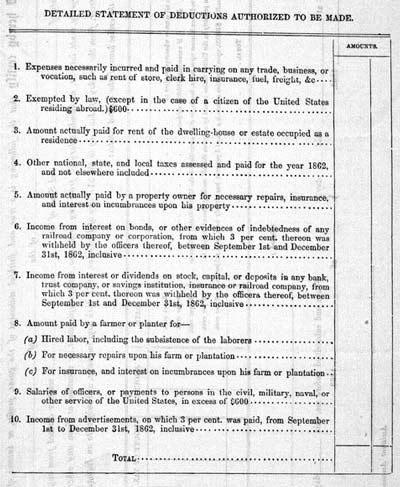

In July 1862, Congress replaced its first income tax with a more workable version including several tax brackets and deductions for state and local taxes, business expenses, and even rent, as illustrated in the above tax return.

Steven’s colleague, Vermont Rep. Justin Morrill, proposed the idea of an income tax, a levy equally shared by all in proportion to each man’s economic status.

On August 5, 1861, President Lincoln signed the congressional bill to institute the nation’s first income tax, requiring a tax of three percent on all incomes over $800. Enforcement of the tax failed, and by the end of the year almost no revenue had been created. Yet an essential step had been taken.

With the Treasury depleted at the beginning of 1862, and with creditors growing angry, the President and Congress resorted to printing $150 million in new paper currency. By this time most people accepted the inevitability of the income tax, and work in the House began anew on a new graduated income tax bill, one that would pass in July 1862 and pave the way for the modern tax code. As one New York Times correspondent wrote in January 1862, “For the present, consequently, we must bid adieu to the golden era in our history in which we were scarcely conscious that we had a Government, so lightly did its burdens rest upon us, and enter upon that in which the almost sole problem of a statesman will be to make the credit balance the debit side of the national ledger.”

How true his prediction turned out to be.