John Brown’s Black Raiders Executed

On December 16, 1859, two of John Brown's black comrades, John Anthony Copeland and Shields Green, were hanged in Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia) for their role in the raid on Harpers Ferry.

They were two of the five African Americans in “John Brown’s Army” whose stories are told in my book, Five for Freedom. The 18 raiders, led by Brown, seized the town’s federal arsenal and rifle works. Brown’s plan was to incite a slave insurrection that would topple the hated institution of chattel slavery. The raid failed in its immediate objective but, many say it sparked the civil war that ultimately abolished slavery.

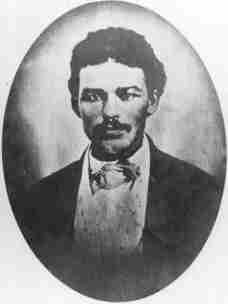

They were hanged together, starting at 11 a.m. on that fateful day, racially segregated from two white raiders whose execution would occur hours later. Shields Green, believed to have been a fugitive slave from South Carolina, died quickly from the hangman’s noose. But Copeland, an antislavery activist from Oberlin, Ohio, died a slow, agonizing death on the same scaffold.

At 23, Green, the youngest of the five, had been living in the Rochester, New York home of Frederick Douglass, where he first met Brown. In August 1859, the two met again with Brown at an abandoned quarry outside Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where they were recruited to join in the raid. Douglass demurred, but Green said, “I think I’ll go with the old man.” Of the raiders — white and black — there was just one survivor, Osborne Perry Anderson, an African American who published the only insider account, in 1861.

Copeland, a carpenter by trade, had spoken at antislavery meetings in Oberlin, where he had also attended the Oberlin school’s preparatory department. On Oct. 18, 1859, Green was captured by U.S. marines who stormed the federal arsenal’s fire engine house where Brown and his band had holed up. Copeland was caught, and nearly hanged on the spot, as he was attempting to escape across the Shenandoah River. From his jail cell, on the morning of his execution, he wrote to his parents, his three brother and two sisters:

The remains of both men went to the Medical College of Virginia, in nearby Winchester, for study and dissection by the students. Copeland’s father sought to bring his son home for a proper burial, but the students refused to relinquish the corpse to an Oberlin emissary.

The two men died in obscurity, but they were not entirely forgotten in Jefferson County. In 1929, Black veterans of the First World War founded the Copeland-Green VFW Post. Months after Copeland’s execution, a memorial service was held at Oberlin’s First Church, where Douglass had once spoke and Martin Luther King, Jr. would speak a century later. On Feb. 12, 2019, I also had the honor of speaking from the pulpit. In addition, the citizens of Oberlin erected a monument to Copeland and Green.

In Five for Freedom, I devote chapters to “The Oberlin Connection,” to the trial and punishment of the African American raiders, including John Anthony Copeland and Shields Green, and to the aftermath. It’s been my privilege to tell the story of these five “hidden figures,” treated if at all as a footnote even by historians sympathetic to the John Brown legend, many times and in many venues, both on Zoom and in person.

Another fallen raider, Dangerfield Newby, was memorialized on a Virginia state highway marker last May. He was nominated for that honor by fourth graders from Fairfax County, Va., whose teacher had read my book. To learn more about the marker,click here .