The Museum of Appalachia celebrates simple, honest life in late 19th Century Tennessee.

-

November/December 2021

Volume66Issue7

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a historian, author of seven books, and Contributing Editor of American Heritage. He regularly publishes essays on his delightful website, The Attic.

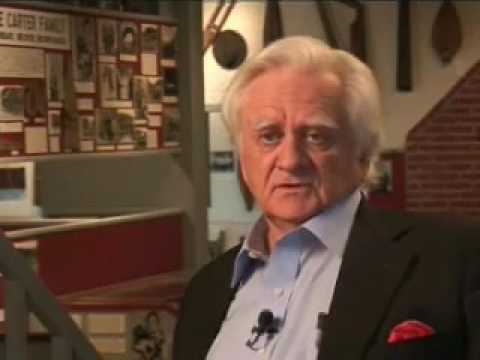

Early in the 1960s, John Rice Irwin dropped in on an auction in his native Tennessee. There he saw the past being sold to the highest bidder. Kitchen tools went for a song. Rusty farm shovels and hoes went unnoticed. Meanwhile, Irwin knew, thousands of pinewood mountain cabins from places like Nickelville and Clinchport and Poor Valley were sinking into the earth. As TV and interstates invaded these parts, a way of life was vanishing.

Irwin bought a few items at the auction, thinking he might put them in the garage. But then he recalled something his grandfather told him. “You ought to keep these old-timey things that belonged to our people and start you a little museum sometime.”

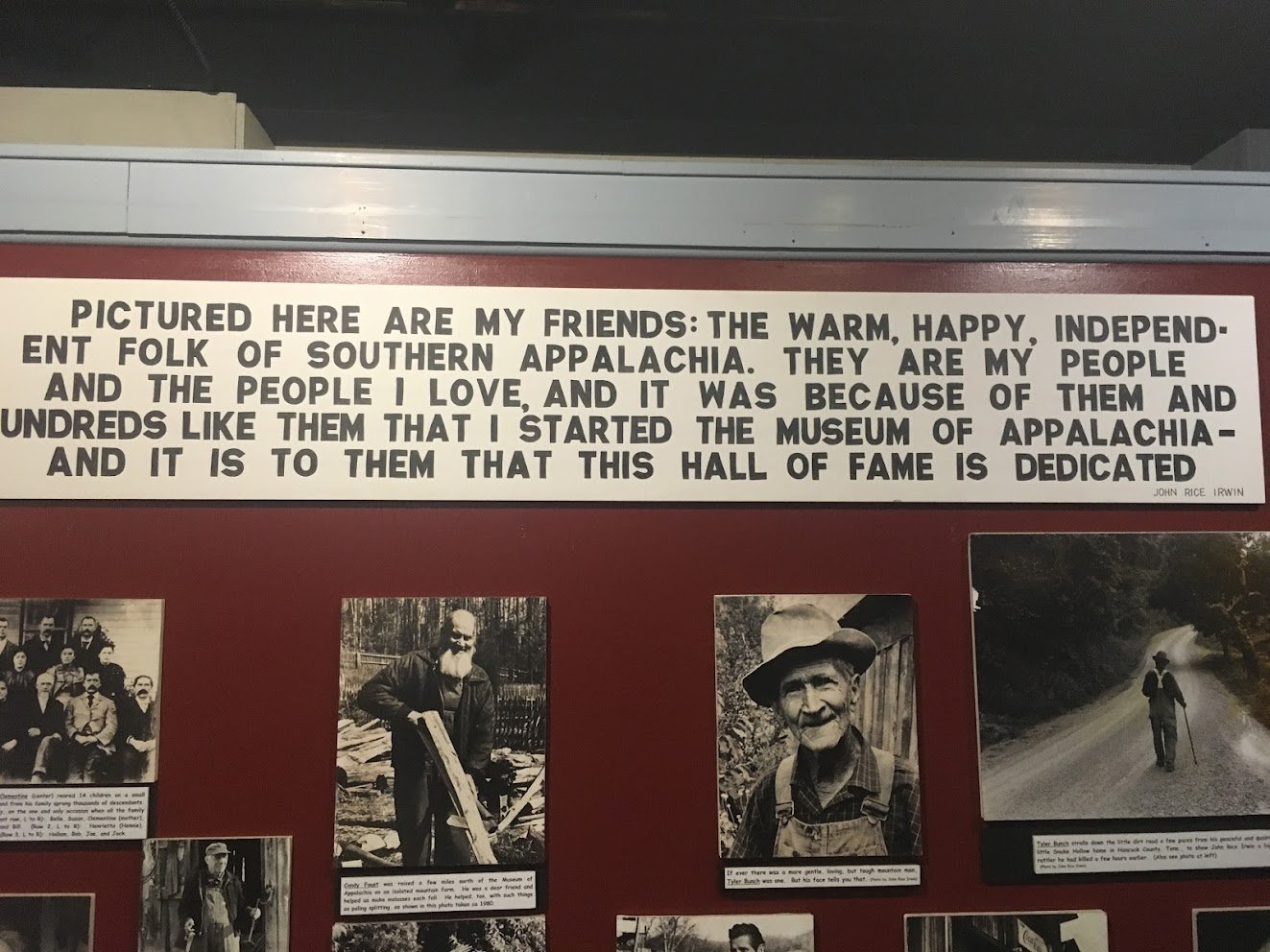

Some geniuses capture their world in words. Others use paint or pixels. But John Rice Irwin, though he played the banjo, was not content to merely join in on old tunes. He wanted to bring the Appalachia he knew as a boy back to life. The hard work. The ingenuity. The tools and toys and crafts and cabins. But above all, Irwin wanted to celebrate the people.

The Museum of Appalachia calls itself a “living history museum.” The Smithsonian calls it “an American treasure.” Located in the foothills north of Knoxville, Tennessee, the museum does the impossible — it conquers time. Step onto its 65 acres and you are in Appalachia, walking through the late 19th and early 20th century.

There are no solemn re-enactments, no people in period costumes. You are the native here. You walk from barn to cabin to grist mill, spotting goats and peacocks on your trail. You hear the banjo and fiddle across a field, see the gardens grow, feel the heat and cold and the hunkerin’ down. But mostly you meet the people.

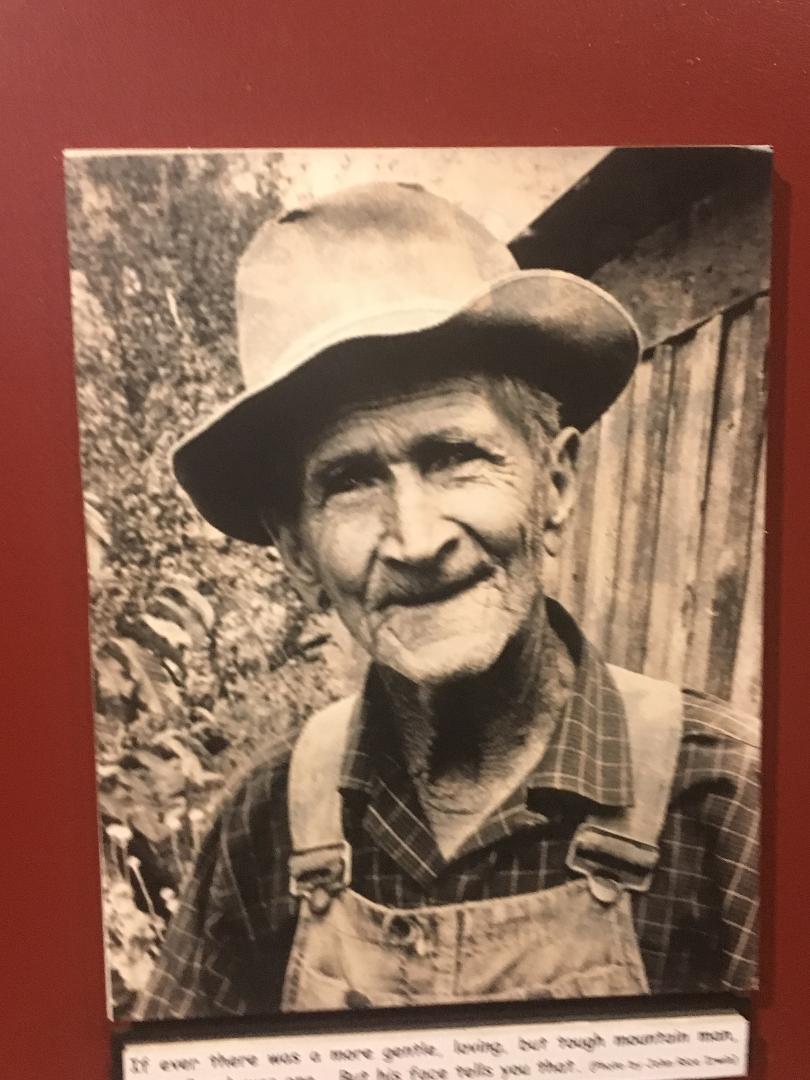

The self-guided tour begins where it should — with human life. In the museum’s Hall of Fame, Irwin pays tribute to Americans who carved lives out of this harsh land. Though often dismissed as hillbillies, they were tough, resourceful folk, living well into the 20th century without running water or electricity. Some became famous. The Hall of Fame pays tribute to country music legends, including Uncle Dave Macon, Dolly Parton and others. But most Hall of Famers here lived and died known only to others. They made their own clothes, their own tools, their own children’s toys. And all of these, some 250,000 artifacts, are yours for the day.

“What better way is there to know a people,” Irwin asked, “than to study the everyday things they made, used, mended, and cherished. . . And cared for with loving hands.”

Display after display, each with a hand-lettered sign, pays tribute to the makers. The museum features whole walls of banjos, fiddles, and dulcimers. Elsewhere stands a full blacksmith shop and a general store complete from sorghum molasses to the latest snake oil. There are tools and tractors, plows and hand-woven baskets, spoons and rifles and every imaginable object whittled on some front porch. And there are the porches. From dark hollows and deep gaps, Irwin gathered old cabins, brought them here and brought them back to life. A dozen cabins, including one that belonged to Mark Twain’s parents before they moved to Missouri, line the gravel walk. Just a glimpse into any hardscrabble house makes the hard life of Appalachia hit home.

From dark hollows and deep gaps, Irwin gathered old cabins, brought them here and brought them back to life. A dozen cabins, including one that belonged to Mark Twain’s parents before they moved to Missouri, line the gravel walk. Just a glimpse into any hardscrabble house makes the hard life of Appalachia hit home.

As it grew from this native soil, the museum struggled for awhile. But by 1980, it had taken root. Word got out that this was not just another collection of old stuff in glass cases. Irwin won a MacArthur genius grant in 1989 and the museum was featured in many magazines. Now, though as remote as Appalachia itself, it draws 100,000 visitors a year. Annual events, include a Candlelight Christmas, a sheep shearing, and assorted concerts. Each visitor returns to our hyper-driven world with a sense of having been there — back in time, back in the hills. And none will ever use term “hillbilly” again.

“These are our people,” said Irwin, who retired from the museum but still lives nearby. “They are world renowned, unknown, famous, infamous, interesting, diverse, different, but above all they are a warm, colorful, and jolly lot, in love with our land, our mountains, and our culture.”