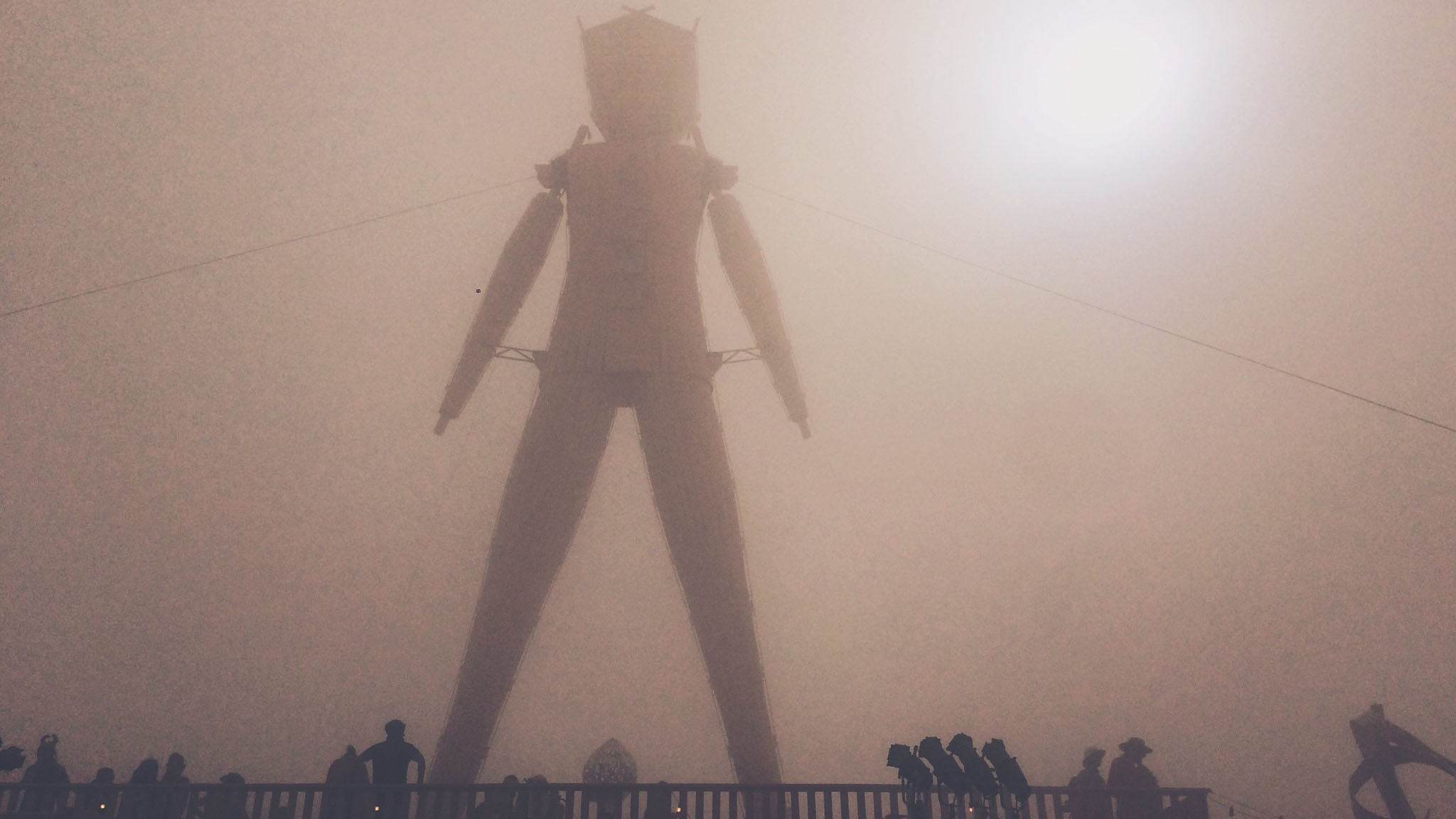

The annual Burning Man Festival in Black Rock City, Nevada, is a week-long binge of festive dress, radical inclusion and pyrotechnic display that has become a spiritual phenomenon.

-

September/October 2019

Volume64Issue4

Bruce Watson is a Contributing Editor of American Heritage and has authored several critically-acclaimed books, He writes a history blog at The Attic.

As the sun set over the Pacific on the longest day of the year, a dozen revelers on a San Francisco beach propped up a wooden man. The first Man.

The Golden Gate Bridge loomed in the distance, but the Sixties cast a longer shadow. The year was 1986, and America was consumed with shopping channels and strip malls. The revelers on Baker Beach felt, as one said, like “remainders on the shelf in Reagan’s America.” One brought gasoline. Another brought matches.

— LARRY HARVEY, FOUNDER OF "BURNING MAN"

Larry Harvey, who suggested that first burn, remembered, “It was just a crude thing stuck in the sand. “The wooden man had wild hair, spindly legs, burlap skin. At the touch of a match, “it practically blew up.” As the Man blazed on, strangers gathered on the beach. People held hands. One sang. The primal fascination with fire took hold and…

Once again this month, a dry lakebed beneath scorching skies will become Nevada’s eighth largest city. A week later, Black Rock City will be gone. In between, 70,000 people will celebrate America’s wildest outbreak of joy — Burning Man.

Describing Burning Man is like capturing the kaleidoscope of childhood. The hope. The fun. The fascination with light, dance, possibility. “Burning Man,” said one Burner, “is about ‘why not’ overwhelming ‘why'.” Burning Man is Halloween crossbred with the annual bender the Romans called Saturnalia. It's the Silicon Valley wired to the Id, the Sixties “long, strange trip” compacted into a single week. And it’s the reason 70,000 people are now headed for the Nevada desert.

Once you’ve paid admission — $425 and rising — Burning Man runs on a “gift economy,” cashless and commodity free. But one concept is pitched non-stop — wonder. Beyond wondering who these people are back home, one can’t help but wonder at the beauty of some installations, the strangeness of others. And while you’re wondering, where does the electricity come from? The water? Will you see any of these people again? Would you want to? And how did Burning Man come to this remote lakebed?

Following the first burn, Larry Harvey and friends gathered the following June to do it again. And again on the next solstice. The Man grew from 8-feet to 15, the crowd from a dozen to 800. In 1990, when police loomed, the torchlit “rave” moved to Nevada. By then, Burning Man had met the Cacophony Society.

Describing itself as “a randomly gathered network of free spirits united in the pursuit of experiences beyond the pale of mainstream society” the Cacophony Society pursued “urban adventures.” A naked cable car ride. A mad climb on the Golden Gate Bridge. Games played in sewers and city streets. One Cacophonist knew how to build. Another worked with neon. Several dated each other. Why not?

Throughout the early 1990s, beneath the pop culture radar, Burning Man grew. Crowds swelled into the thousands and the man grew to 40 feet. Artists, dancers, musicians, and assorted zanies joined in. Groups gathered around themes. Then the festival added its own annual themes — Good and Evil, Inferno, Wheel of Time. And like something out of Star Wars, temples rose from the sand. The Temple of Mind, Tears, Joy, Stars, Dreams…

By 2000, crowds of 25,000 needed new rules. No dogs. No guns. No fireworks. But the festival also had ten guiding principles. Among them: radical self-reliance, radical self-expression, civic responsibility, and leaving no trace. The latter requires Burners to clean up the entire city using buckets labeled MOOP (Mutant Object Out of Place).

After the festival was televised in 2006, critics accused Burning Man of being too crowded, too expensive, too wasteful. But cops and the Bureau of Land Management kept watch, issuing hundreds of citations each year. The nearby town of Gerlach (pop. 210) fostered a love-hate relationship, resenting the crowds but making a bundle. And the Burners kept coming. Attendance was capped at 50,000, then 70,000. The man grew to 100 feet. In 2014, the Burning Man corporation, with 50 staff and 4,000 volunteers, became a non-profit, awarding $500,000 in artists grants each year.

Along with documentaries, novels, and TV shows, Burning Man has inspired dozens of spinoffs. Burning Flipside in Texas, Kiwiburn in New Zealand, Midburn in Israel… As Barbara Ehrenreich noted in Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, “The urge to transform one's appearance, to dance outdoors, to mock the powerful and embrace perfect strangers is not easy to suppress.”

Larry Harvey died in 2018 at age 70, but The Man lives on. This year’s theme, Metamorphoses, will draw another horde of Burners. Some will ride mountain bikes through the makeshift urban grid. Others will drive Mutant Vehicles — giant snails or dragons or cupcakes on wheels. A handful will walk around naked. There will be costumes, torch dancing, acrobats, soaring statues, and shameless exhibitionism. Why not?

“There ought to be Burning Man festivals held downtown once a year in every major city in America,” Wired wrote. “It would be good for us. We need it. In fact, until we can just relax every once in a while, and learn how to do this properly, we're probably never gonna get well.”

Bruce Watson, a Contributing Editor of American Heritage, writes for our website and his own at TheAttic.space.