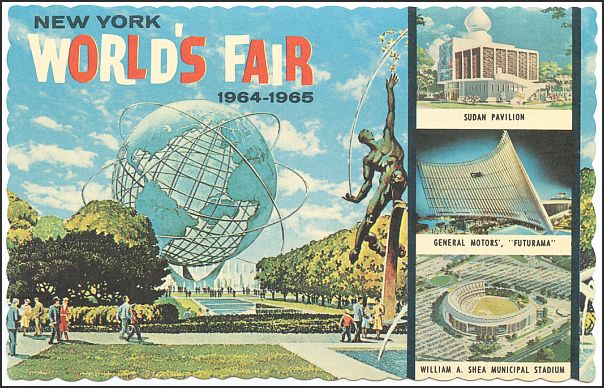

The Last Great World’s Fair

By rights, New York City should be in the midst of planning a new world’s fair. In fact, it’s long overdue. The city broadsided the Great Depression with the 1939 World’s Fair and saluted the nuclear age with a fresh edition that opened 53 years ago today, on April 22, 1964.

Since then, world’s fairs have largely gone out of style, replaced, perhaps, by the televised sense of community offered by the biennial Olympic Games. World’s fairs were never on a schedule, though. Whenever a city felt the urge, it invited the world in for a massive show-and-tell (and eat), and the result was a notch in the memory of anyone who attended.

When the New York World’s Fair of 1964 was first proposed, it was promoted as a celebration of the city’s 300th birthday. Everyone in the metropolitan area was thrilled with the idea, except those historians who shook their heads and tried to explain that New York had actually been founded in 1626, not 1664 (when it was, however, captured by the British and given its modern name). The birthday theme was eventually overshadowed anyway by an anodyne motto, Peace Through Understanding.

The New York World’s Fair was not likely to be late in opening, however murky its sense of history. Thomas J. Deegan Jr., the suave chairman of its organizing committee, and Robert Moses, the president, were nothing if not forceful. Once the idea was launched, in 1959, they steered the construction through five hectic years with only an occasional wobble. Deegan, a self-made man, had started as a stringer for The New York Times and risen through the ranks of journalism and public relations until he was helping to run railroads and other industrial concerns. Moses, educated at Yale, Oxford, and Columbia, thrived in the world of New York politics and was well-established as a builder of parks and highways and overlord of public projects in both the city and state.

Moses’s first job for the fair was modernizing transportation to the site, Flushing Meadows, in Queens. In the early part of the century, the area had been used as a dump for industrial waste (it was immortalized as the Valley of Ashes in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel The Great Gatsby). It was cleaned up for the 1939 fair, but by 1960 it was just a windy park, where mothers took their children for walks on the old, cracking sidewalks left over from 1939. Now it was transformed again. In the years leading up to the opening of the new fair, as many as 10,000 construction workers were busily engaged there at any one time.

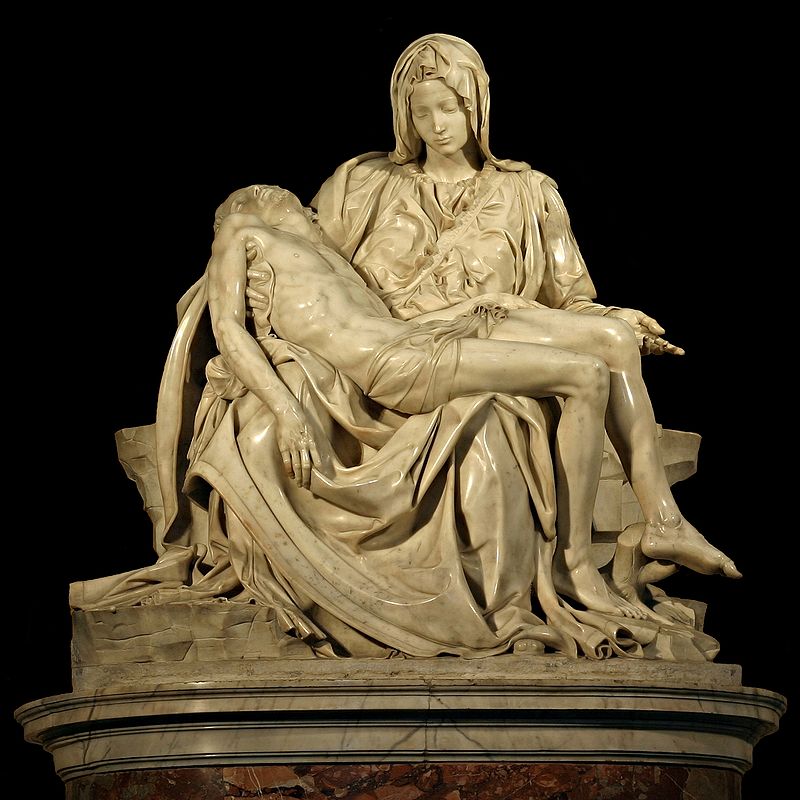

Deegan was responsible for the grand coup of the fair, the installation in the Vatican pavilion of Michelangelo’s Pietà. The tiny nation-state Vatican City, home of the Holy See, did not normally participate in promotional activity. Getting a Vatican pavilion was impressive enough, as a reflection of the importance of the fair, but the fact that the authorities agreed to move Michelangelo’s great sculpture of Mary holding her dying son from its place at St. Peters Basilica was nothing short of incredible.

The Pietà had been in St. Peters since 1499, when Michelangelo himself smuggled it inside under the cloak of night, lest Pope Alexander VI refuse to allow its display. (The artist evidently brought a battalion of his strongest friends with him for the delivery; the sculpture weighs approximately 10,000 pounds.) In response to the Vatican’s gesture, the government of Spain grandly announced plans to send El Greco’s painting The Burial of Count Orgaz to the fair. Long before moving day, though, it was decided that the risk of damage during transit was too great, and that offer was withdrawn.

There were no such second thoughts in Rome. The Pietà’s journey began on April 6, 1964. It was secured inside three nested crates, and just in case the ship transporting it sank to the bottom of the ocean, the crates were lined with buoyant material and equipped with a signal emitter. The captain nervously noted that if the vessel went down he would be world famous as the man who lost the Pietà. He didn’t want to be world famous.

The Fireman’s Fund Insurance Company underwrote the special policy covering the trip, and a vice president of the firm was among those standing on the pier when the crate was unloaded in New York. Watching it dangle in midair, he blurted out, You people can afford to be calm, but I’ve got $6 million hanging by those cables up there. Six million dollars would hardly have covered the loss to the world—and the fairgoers would prove that point.

The opening day of the fair, April 22, was in the midst of springtime, but it felt like football weather to everyone present—blustery, cold, and wet. That didn’t spoil the fun, though, and neither did the presence of a few hundred protesters using the fair as a backdrop to, as one of them put it, point up the contrast between the glittering world of fantasy and the real world of brutality, bigotry, and poverty. As the protesters tried to sit down in the way of the fairgoers, a woman on the way in barked at her six-year-old daughter, “When I say step on them, step on them!”

At the opening ceremony, President Lyndon Johnson received polite applause when he hammered home the theme of peace; former President Harry Truman received a standing ovation, just for being himself and making a few jokes. You are as kind as you can be to ask an old has-been, he said near the beginning of his remarks. The crowd called out, No! He later referred to the theme of the fair and confided that he had tried to have the United Nations headquarters situated in Missouri. But I didn’t have a Chinaman’s chance, he concluded. After the speeches, the initial mornings crowd of about 20,000 fanned out across the fairground and took it all in.

At the General Electric pavilion, nuclear fusion was demonstrated—every six minutes. Sweden brought the world’s oldest stock certificate to the world’s financial capital; dated June 12, 1288, it represented a one-eighth share in a mining company called Stora Kopparberg (which is still in operation). The state of Illinois brought a robot version of Abraham Lincoln, which recited bits and pieces of his speeches. The Hollywood pavilion went in the other direction, trading fantasy for reality by staging live versions of scenes from classic movies. New York City offered a tour of the city from above; visitors rode in a gondola over a meticulously accurate model said to include 800,000 buildings in all five of the boroughs. (It still exists, recently refurbished, on the site.) The Swiss exhibited a clock so accurate it detected inconsistencies in the movement of the earth.

Over the course of two seasons, 1964 and 65, 51 million people paid admission to see the New York World’s Fair. Fifteen million of them chose to wait in the long lines that perennially snaked out of the General Motors Pavilion, where visitors sat in chairs that moved through displays showing the world in the year 2024. GM spent $50 million on the exhibit, and apparently it was money well spent. GM’s World of Tomorrow was the most popular exhibit at the fair.

The second most popular attraction—one in which visitors could not sit down—was the Pietà. Displayed in a small room, all cloaked in a rich dark blue, the statue was shown in light just bright enough to draw out the details. Visitors were drawn slowly past the Pietà on a moving sidewalk. Lingering wasn’t allowed. It was situated in a position said to have been preferred by Michelangelo, meaning that even people who had seen it in Rome were seeing it anew in New York. For most of the 14 million who saw it, though, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. That was the ambition of every world’s fair—and the accomplishment of only a few.