30 Years Ago: Gary Hart's Monkey Business, and How a Candidate Got Caught

Thirty years ago this week, rumors began circulating about the supposed extramarital affairs of Sen. Gary Hart, the leading candidate for the 1988 Democratic nomination for President.

In response, Hart challenged the media. He told The New York Times in an interview published on May 3, 1987, that they should follow me around. . . . They’ll be very bored. As the NBC anchor John Chancellor explained a few days later, "We did. We weren’t."

Seldom if ever has a major presidential candidacy crashed and burned so quickly. On May 8, 1987, a mere five days after issuing his challenge, the Colorado senator withdrew as a candidate. He would reenter the race the following December, but he would then withdraw a second time after winning just 4 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire primary in February 1988. His political career was over.

Hart, the son of a farm-equipment salesman, was born in Ottawa, Kansas, in 1936, with the surname Hartpence (he legally changed it in 1965). He attended a local college and then went to both Yale Divinity School and Yale Law School. He practiced law for several years in Denver and then took on the task of running the very long-shot campaign of Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination.

It made his political reputation, for it turned out that the McGovern campaign had a secret weapon. After the 1968 Democratic Convention was marred by riots in the streets of Chicago outside and near chaos inside, the Democratic Party established a commission to reform the nominating process.

Its recommendations, adopted by the party, sharply curtailed the power of elected officials and party insiders to choose delegates, increased the importance of caucuses and primary elections, and mandated quotas for blacks, women, and youth. The chairman of the commission, Sen. George McGovern, understood far better than the other candidates how much the rules had changed the political landscape. Hart exploited that understanding to the hilt.

While McGovern took only one state and the District of Columbia against Richard Nixon, no one blamed this on Hart. Two years later, Hart captured a Colorado Senate seat in the Democratic landslide of 1974, and he was reelected easily in 1980. He ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984, and though he lost out to the more senior Walter Mondale, who had served as Jimmy Carter's Vice President, he established himself as a serious candidate who was young, attractive, articulate, and seemed to offer new ideas.

He declined to run for reelection to the Senate in 1986 in order to devote his full attention to winning the 1988 Democratic nomination for President. Against a lackluster field, polls soon showed him far ahead of his nearest rival, more than 20 points in some polls. But he had a major problem, a persistent buzz of rumor regarding his private life and being a womanizer. He and his wife, Lee, had been married for more than 25 years and had two children, but the marriage was apparently a troubled one. They had separated twice and reconciled twice.

A story in Newsweek around the time he formally announced his candidacy, on April 13, 1987, highlighted these rumors, and while it made no specific allegations, it quoted a former adviser as saying that Hart was going to be in trouble if he can't keep his pants on. This produced a barrage of stories in other newspapers and magazines but, again, nothing concrete.

Then, two weeks after Hart’s announcement, the executive editor of the Miami Herald, Tom Fiedler, got an anonymous phone call. The caller said she had proof that Hart was having an affair.

Fiedler was not, at first, impressed. Told that the caller had photographs of Hart and a friend of hers, an attractive blonde in the Miami area, Fiedler said that politicians had their photographs taken with strangers all the time; it proved nothing. But then the caller told him about phone calls her friend had received from Hart from various places over the past few months, and the dates when those phone calls had been received.

Fiedler was easily able to check them against Hart’s schedule, and they coincided. If it was a crank call, someone had gone to a lot of trouble to make the tip appear genuine. But he was wary of a professional dirty trick. She then told him that her friend was flying up to Washington that Friday, May 1, to spend the weekend with Hart at his Washington, D.C., townhouse. Fiedler knew that Hart was scheduled to be in Iowa Friday and then in Lexington, Kentucky, on Saturday, which was Derby day. He also thought that Hart lived in Bethesda, Maryland, not in the District. But checking the next day, he learned that Hart had sold the house in Bethesda and had indeed moved to Washington, to a townhouse on Capitol Hill. He also learned that the Kentucky stop had been cancelled; Hart was spending the weekend in the District of Columbia. Fiedler’s journalistic instincts told him he was on to something big.

He and a senior editor decided that Jim McGee, an investigative reporter, should catch a Friday afternoon plane to Washington—the flight most likely to have the mystery woman—and stake out Hart’s house. McGee barely made the 5:30 flight. On it he noticed one particularly striking blonde. Could this be her?

Staking out Hart’s house that evening, McGee saw Hart’s front door open at about 9:30 and a man and woman emerge. It was Hart and the blonde on the plane.

The next morning Fiedler and a photographer arrived on the scene. They thought it crucial to have the sighting confirmed, and that evening they saw Senator Hart and the woman emerge from the back entrance of the townhouse. The couple went to Hart’s car, which was parked a short distance away, but then returned to the house through the front entrance. Hart seemed agitated, as if he sensed he was being followed. When he came back out the back entrance, the reporters decided to confront him.

He denied that the woman had spent the night at his house and gave several lawyer-like denials of any impropriety. The reporters, facing a rapidly approaching deadline, decided to go with the story, which appeared in the Sunday, May 3, edition of the paper, with the headline Miami Woman Is Linked to Hart. It caused a sensation.

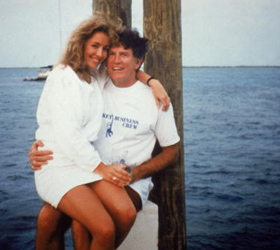

It soon emerged that the woman’s name was Donna Rice, and she had met Hart at a New Years Eve party in Colorado. She had later accompanied him on an overnight trip from Miami to Bimini on an 83-foot luxury yacht with the you-cant-make-this-stuff-up name of Monkey Business. A picture soon appeared in the National Enquirer, and then in hundreds of newspapers, showing Donna Rice sitting in Hart’s lap, with Hart in a Monkey Business T-shirt.

At a press conference on May 6, the senator furiously denied doing anything wrong. If I had intended a relationship with this woman, he said, believe me . . . I wouldn’t have done it this way.

But contributions to his campaign were rapidly drying up, and his lead in an overnight poll in New Hampshire fell by half. The Washington Post informed the campaign that it had good information on another liaison of his. On Thursday he flew home to Colorado, and on Friday, May 8, he announced his withdrawal from the race.

Gary Hart’s political career began with the crucial insight that the rules of the game with regard to getting delegates to the Democratic convention had fundamentally changed, thanks to the debacle of the 1968 Chicago convention. His political career ended because he failed to realize that the rules of the game with regard to the private lives of politicians had also fundamentally changed, thanks to the debacle of Watergate.